In a major test, Orange County schools reopen to joy, anxiety and gallons of hand sanitizer

- Share via

On Thursday morning, months of finely-curated planning will be turned into action at five Orange County school districts serving about 76,000 students as schoolyard gates open for in-person classes for the first time in six months, marking a widely watched return to school amid California’s coronavirus crisis.

The Tustin, Irvine and Los Alamitos unified school districts and the Fountain Valley, Huntington Beach City and Cypress school districts are among the first cluster of public school systems in the 29-district county to begin opening this week — with hybrid schedules that allow a portion of students back at one time while others learn online to keep classes small to maintain social distancing.

Next week, five more will open: Newport-Mesa, Capistrano, Saddleback and Orange unified and Ocean View schools. These first days bring both celebrations and deep concerns among teachers and parents about safety as their reopening experiences will stand as harbingers of what may lie ahead throughout the state.

The openings come after Orange County — known for its anti-mask rebellion and defiance of state orders — was given state and county public health department clearance to reopen campuses because of the county’s lower coronavirus test positivity rate. Out of 29 school districts in the county, 10 have announced plans to open for in-person instruction by the end of the month.

“It is with great excitement that we welcomed our elementary-age students back to school, returning for in-person learning with their teachers and support staff,” Fountain Valley Supt. Mark Johnson said. “The joy of being back on campus with their teachers and classmates was evident throughout the day and hopefully made each of us feel a little more connected again.”

Second-grade teacher Lisa Hickman of Tustin’s Sycamore Magnet Academy expressed the joy and anxieties of a complicated and new classroom order: masks, desk dividers, hand sanitizer by the gallon, staggered schedules, dots on the floor indicating how close students can get to her. But more than anything else, she was excited to finally meet the 7-year-old children whose voices and laughter she has known for weeks through the computer screen and audio of distance learning.

The Huntington Beach City School District’s hybrid learning plan has children going back to school on Oct. 26, at the earliest. Nearby districts are reopening next week.

“Everyone wanted us to reopen, and I felt like Orange County was rushing it. ... I’m terrified for the safety of my coworkers and my students, they’re my babies,” she said. “But right now our main concern is how to protect the kids.”

The districts that are reopening serve mostly affluent communities where COVID-19 rates are lower than districts serving mainly low-income households, including Santa Ana and Anaheim — developments that have raised equity concerns among some educators.

Unresolved are the safety concerns voiced by teachers in Irvine, Newport-Mesa and Saddleback Valley who protested their district openings last week, saying their schools are not ready to welcome students, teachers and staff back on campus safely during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At Newport-Mesa, where 8,000 preschool to sixth-grade students are expected to return on campus this week, union President Tamara Fairbanks said concerns raised during their Sunday caravan protest remain.

“We feel that the district is rushing into it without further thought of the ideas they’re implementing,” Fairbanks said.

Newport-Mesa school board President Martha Fluor said the district continues to work with the union.

“We are continuing to negotiate with teachers. We are meeting or exceeding the standards in all aspects. Given that Orange County has moved to the Orange Tier, we’re confident that we can resume in-person learning in a safe manner,” Fluor said, referring to the state tier that allows for school and other business reopenings.

Irvine and Saddleback teachers also pushed back on reopening plans by circulating petitions and sending them to their school boards.

Over 257 teachers in Saddleback Valley signed a petition, calling to push back the Sept. 29 start date and re-evaluate the hybrid learning model. Meanwhile, teachers at the Irvine Unified School District wrote an open letter and collected over 2,000 signatures on a petition against the district’s reopening next week, citing a lack of preparation and unclear safety protocols.

“The hybrid model is not a return to normalcy. It will not improve the educational outcomes,” the Saddleback Valley statement reads. “It will not improve socialization. It will not improve our well-being.”

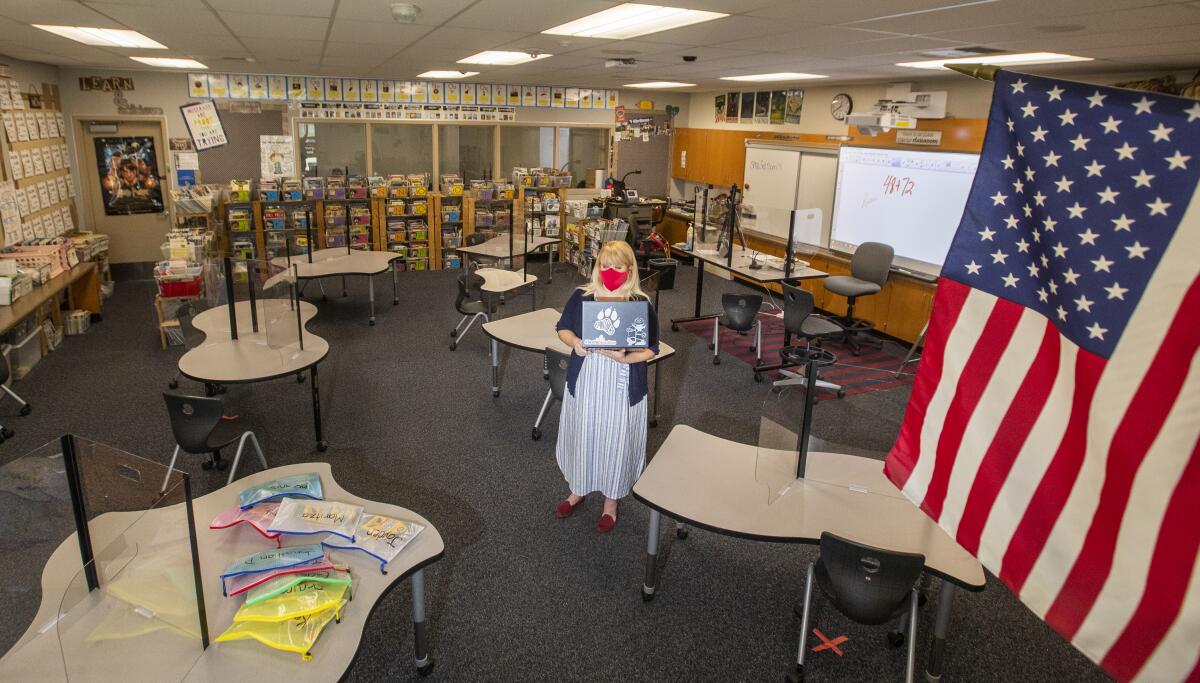

Still, teachers across the county are preparing for the week ahead. Hickman spent Wednesday afternoon setting up her classroom for the first day of school.

She attached plastic screens to each table and organized school supplies for the students, since they could no longer share supplies. Days before, she installed a temperature check on the wall by the door for students to pass by before entering the classroom.

NMUSD employees rallied in a motorcade Sunday to protest the district’s reopening schools next week, saying supplies and personnel are not in place and union talks are still ongoing.

In the front of the room, she tested out the setup for her “teacher island,” which consists of an iPad on a tripod, a headset, her laptop with Google Meets open and the smart board for writing. The setup will allow her to teach online and in person simultaneously.

The pandemic has upended the teaching methods she has all but perfected during 17 years in the classroom.

“Gone are the group projects, the art projects, the 6,000-book library. Gone is me going up to a student’s desk to help or telling them to ask a classmate,” Hickman said.

When a student has a question or requires assistance, they’ll make their way over to a yellow Velcro dot on the floor that is a safe distance from her and the other classmates.

In between her morning and afternoon class, Hickman said, teachers will use an aerosol disinfectant to clean off all of the surfaces before the next group of students arrives. The classroom cleaning during the day will likely fall on teachers due to a small custodial staff.

Outside James H. Cox Elementary School in Fountain Valley, a line of 3-foot-tall children carrying oversized backpacks walked in a single file line promptly at 2:15 p.m. to the parking lot. A kindergarten teacher led the fleet with a paper sign “We survived!”

One by one, the children were reunited with their parents.

Just minutes later, the bell rang and students from older grades fled out into the front entrance to find their parents who were waiting widely scattered across the front of the school.

Orange County allowed all of its schools to reopen Tuesday for the first time since March. Teachers say schools still aren’t ready to welcome students and staff back on campus safely during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kim Rincon, 42, searched through the sea of tiny humans to spot her 9-year-old daughter Jordan, who had just completed her first day of fourth grade. She tapped her left foot in nervous anticipation as she held her 4-year-old son Dylan.

“My fears are the same as everyone else. I don’t want my [child] to get sick and then then bring it home and get the family sick,” she said.

The safety protocols in place put her at ease, but as a teacher in a different district, she said she was concerned if schools would follow through.

A wave of relief passed when Rincon spotted her daughter, lugging a math workbook and blue lunch bag.

“How was school?” Rincon asked.

Jordan replied with her go-to response, “Oh, good.”

That nonchalant response brought back a sense of normality: meeting new — though fewer — classmates, learning the new rules of the classroom and catching up with friends in a three-hour school day.

“I was nervous about my safety for the first day, but I’m pretty happy about being back,” she said with a shrug.

During a socially distanced recess, she reunited with friends, though some of her classmates chose to play on the playground with less distance separating them. Still, she said, the students were monitored by teachers.

Just 10 miles away, parents at Los Alamitos were also adjusting to their new schedule.

Frederick McCord, 33, dropped off his daughter Kimora at Los Alamitos Elementary School at 8:15 a.m.

The dropoff and pickup organization flowed with little interruption. To avoid crowding, parents were assigned a specific gate and time at which to arrive.

“So far, I haven’t had any problems,” McCord said. “But of course I’m nervous. I trust the school is taking care of the children, but I’m always worried about the what if.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.