O.C. district attorney drops or reduces charges in 67 cases over mishandled evidence

- Share via

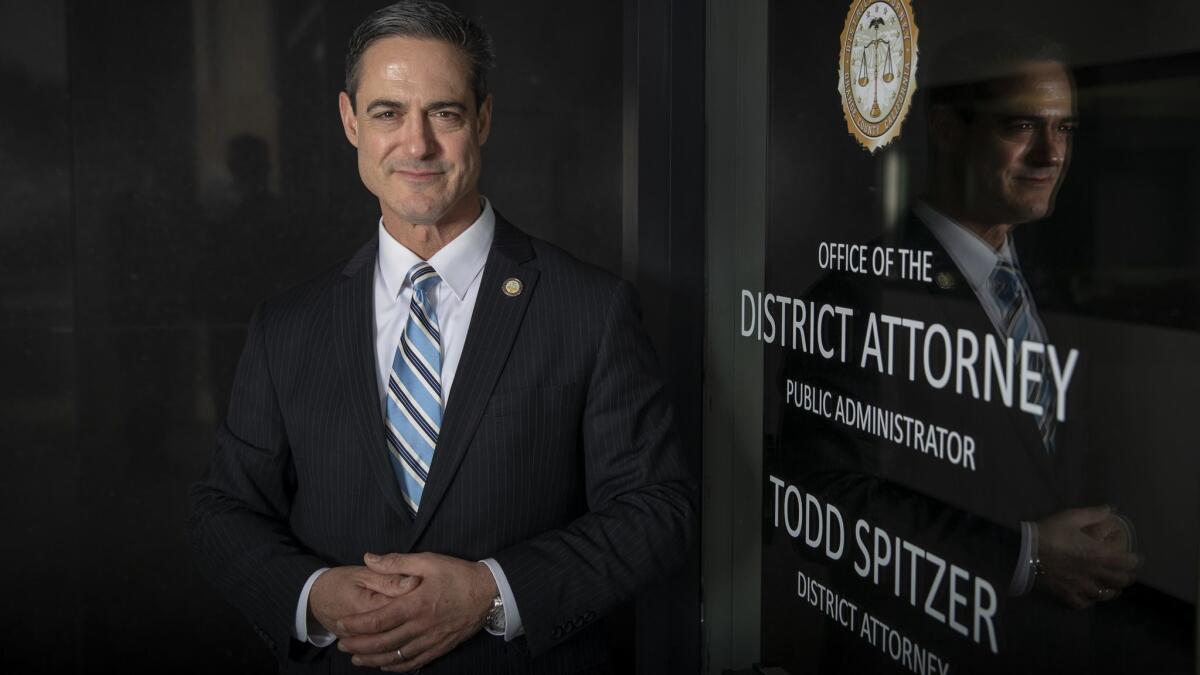

Orange County Dist. Atty. Todd Spitzer reduced or dropped charges against 67 defendants — many of whom had already been convicted — after a series of audits revealed that sheriff’s deputies booked evidence late or failed to book evidence completely, prosecutors announced this week.

The affected cases involve alleged battery, assault, drug possession and one incident in which a person was accused of smuggling a weapon into the county jail, according to the district attorney’s office, which made the announcement on Wednesday. In 63 of the cases, the defendants had already been convicted of the charges. In four, charges were dropped or reduced while the cases were still pending.

Spitzer’s decision came after a series of lengthy reviews of thousands of Orange County Sheriff’s Department cases in which deputies had potentially mishandled evidence. The department’s policy requires evidence to be booked by the end of each shift, but two internal audits found that deputies routinely booked evidence late or failed to book evidence at all despite having written in their reports that they had done so.

Sheriff Don Barnes said in a statement that his department took immediate measures to address the situation and implement safeguards to ensure it does not happen again. He added that the agency has “no tolerance for substandard performance or criminal behavior.”

“Once this issue came to light, we determined the extent of violations, identified areas for improvement and held accountable those employees who were acting out of the scope of policy,” Barnes said. “Randomized spot checks of booked evidence are being conducted regularly, and have confirmed that the new policy and procedures are being followed.”

Unsatisfied with the scope of the initial two audits, Spitzer ordered a third audit, in which a joint team of Sheriff’s Department and district attorney’s office investigators reviewed 22,289 cases that had resulted in convictions over a three-year period, ending in March 2018. Ultimately, the team determined that more than two dozen of the cases reviewed merited a dismissal or reduction in charges, according to a district attorney’s office report.

“The D.A.’s office will continue to review cases and provide notice to the defense when appropriate to ensure that defendants’ due process rights are protected, but because of remedial action [the Sheriff’s Department] has taken to address evidence booking deficiencies, there should be few, if any, negatively impacted cases in the future,” the report states.

Prosecutors have also reviewed potential criminal charges against 31 deputies as part of the probe.

Spitzer had initially declined to charge any deputies but later reversed course and said he had not realized the scope of the alleged misconduct. Sixteen deputies have been added to the Brady Notification System, which tracks law enforcement personnel with a history of dishonesty or misconduct. Three have faced criminal charges as part of the scandal and 14 could still be charged, according to the report.

Two former deputies — Joseph Anthony Atkinson Jr. and Bryce Richmond Simpson — have both pleaded guilty to one count of willful omission to perform their duties. Each was sentenced to one year of probation. A third deputy, Edwin Mora, was indicted with a felony over the summer for allegedly filing a false police report about evidence. He is scheduled to appear in court for a pretrial hearing in February.

Orange County Assistant Public Defender Scott Sanders, who has revealed significant details about the scandal in court filings over the last year, said the situation is “far from a success story of a rapid response addressing systematic misconduct.”

“We weren’t going to learn any of this, and there certainly was no intent to inform us about the massive scope of false reporting and failures to book evidence,” he said. “We obtained the audit through a source and it then became public, more than a year after the massive scope of the problem was understood by the OCSD. That’s why action was taken. And the real work is just beginning.”

Hannah Fry is a staff writer with the Los Angeles Times.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.