Studs Terkel Still in Hot Pursuit of the People’s History

- Share via

Studs Terkel, oral historian, disc jockey and liberal, has a fantasy--he’s transported in time to the day that Jesus was crucified.

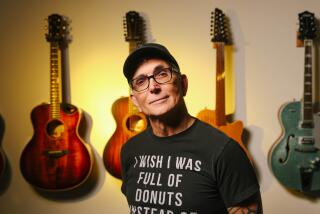

As he explained his fanciful wish, Terkel leaned forward, red tie skewed across red-checked shirt, white hair (that he insists makes him look like Spencer Tracy when combed a certain way) spraying across his head, voice rising and falling for dramatic effect:

“I got a tape recorder and it’s the day of the Crucifixion and I’m at the foot of Calvary. And he’s going up lugging this heavy cross. They’re going to execute this guy. Who is he? He’s the head of an underground movement during the time of the Roman Empire. He’s the commie of the day. What’s he saying? ‘You’ve got to cooperate with your neighbors, you’ve got to love them.’ Enemy! And you don’t look down on someone who’s less than you. And there’s a young Roman soldier with a helmet on and he’s not Victor Mature. He’s a pimply faced kid and he’s scared stiff and he doesn’t know what’s going on, like a young National Guardsman during the Flint strike of 1937.

“And then there’s some followers of this guy who’s lugging the cross up and they’re scared and they don’t know what to do. Then you’ve got some informers. You got Judas who’s going to spill it before what I call the House Un-Roman Activities Committee. And then you got the judge, who’s not a bad guy, the judge is washing his hands. And you’ve got the judge’s wife who’s sympathetic to this guy. Something’s going on here. Well, that would be interesting, wouldn’t it?”

Terkel leaned back and grinned, delighted by the slightly irreverent illustration of what he does. He has become famous for scorning official documents. This 72-year-old energetic elf of a man prefers the people who lived history to the papers that recorded it, whether it’s the New Testament or mortgages foreclosed in the Depression. Preferably, the people he portrays are participants, not managers, of great events. He is interested in the common man’s response to a world beyond his control. The pharaohs and Caesars have gotten too much credit for history, he asserted.

While maintaining his long-running radio show of interviews, dramatic readings and jazz at a Chicago station, Terkel has produced five volumes of oral history that chronicle American life in the 20th Century, including “Hard Times,” “Working,” “Division Street: America” and “American Dreams: Lost and Found.”

His latest is “The Good War: An Oral History of World War Two” (Pantheon: $19.95). The title is meant ironically, Terkel said, because “there is no such thing as a good war.” But that conflict was clear-cut and the United States won, giving it an aura of might doing right that Vietnam and Korea did not have and have not acquired, he said.

Kept Stateside

Terkel, who described himself as “anti-war,” was one of those who was eager to go overseas, he recalled. But a perforated eardrum kept him stateside where he was in “Special Services, the same thing (President) Reagan did here. I wrote a speech for a colonel now and then.”

“The Good War,” Terkel said, is a continuation of his chronicle of the Depression, “when the economic machine stripped a gear and the guy with the top hat slipped on a banana peel.” The war finally closed the books on that economic catastrophe and opened the path of prosperity to millions of veterans as well as drawing the lines for the Cold War, he noted.

“There were 11 million unemployed in this country in 1939 and that’s when the Germans invaded Poland,” Terkel said. “It was war that ended the Depression. This is the irony; World War II came along and the whole world changed. And then came the GI Bill, which enabled a guy for the first time in the history of a family to go to college. First time! And that meant he’s not going to work on the assembly line or as a laborer as his father did. What he’d become, in his own mind certainly, was middle class. And then came the new suburbs. Who lived in the suburbs before World War II? The rich lived in suburbs.”

Although it did not surface immediately, the war also contributed to the women’s movement by taking millions of women out of their homes and into factories, Terkel added.

But these social changes have occurred against the dark backdrop of the East-West split, he said. And it is the superpower conflict that he sees as the most enduring and fearsome legacy of the war. The Russian bear, he said, has become a fixture of our subconscious. As such, Terkel said, he’s found that many Americans have a automatic reaction against the Soviet Union that excludes its former role as ally and victim. That country lost at least 20 million people in World War II, he said.

That’s one reason Terkel has included interviews with Russian veterans in “The Good War,” he said. He also has recorded the memories of a few Japanese and Germans, he added, to show what their side of the war was like.

Nonetheless, Terkel is clearly most interested in the American servicemen he interviewed. “There’s no doubt that for many guys this was the high moment,” he said. “This is the irony. It’s a barbaric adventure but the guys remember. . . . One guy says, ‘For me the last act was shot in the first reel.’ Here’s this man who was a 19-year-old rifleman who’s now a man in his 60s remembering every detail.”

Terkel is also fascinated by the savagery of the war, especially in the Pacific. During an interview he returned several times to the story of E.B. (Sledgehammer) Sledge, a former Marine who is now an ornithologist at an Alabama college. “If there’s ever a guy who doesn’t look like a Marine, it’s him,” Terkel said. “But he was there and he’s remarkably honest about it . . . the guys would use the K-Bar, which is a seven-inch knife, to chop the gold teeth out of a corpse, or a guy not even dead.”

To find his interview subjects Terkel said he relies on a combination of luck, hearsay, coincidence and research. Over the years he has made many contacts throughout the country that he relies on, he added. Once he was lucky enough to catch a ride with a cabdriver who fit neatly into a book. “I liken myself to a gold prospector,” he said.

When he ultimately discovers a nugget, Terkel said that he seldom has trouble turning it into pure gold. “When there’s someone who’s never been interviewed about his or her life, that person opens up like sluice gates open, if that person feels that you are serious, that you really are listening,” he said.

“The Good War” has been on best-seller lists for some months now and Terkel has discovered that it is being given as a present to many of its veterans. “When I sign the book in a bookstore, a lot of women who are in their 30s come up and say, ‘Sign it ‘To Pete.’ It’s their father,” he said.

Terkel suspects that many are like the veteran who told him, “It’s a war I go to every day.”