It’s Not Just for Mexicans Anymore

- Share via

The festivities are about to begin.

Thirteen-year-old Luis Paz, whose parents are from Guatemala, is looking forward to partying with friends.

Luis Villacorta, Paz’s classmate at Hammel Street School, said that when the time comes he will feel Mexican, even though his roots are in El Salvador.

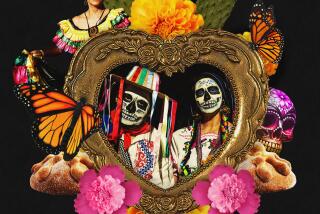

It is Cinco de Mayo, a Mexican holiday that is more popular among Mexican-Americans and Latino immigrants here than among people in Mexico. Hundreds of thousands will join in the festivities Friday and this weekend with rousing celebrations featuring Mexican music and food at dozens of schools, civic sites and parks.

Increasingly, the holiday is also being embraced by others as a marketing opportunity or a good excuse to party.

The holiday today is “celebrated very much in the spirit of a generic holiday,” said Mauricio Mazon, a USC history professor. He lamented that the holiday has been “watered down.”

Historically, Cinco de Mayo refers to May 5 of 1862. On that day a small, poorly armed force of Mexicans defeated thousands of French troops, which had been deemed to be almost invincible, in the battle of Puebla.

While the French went on to dominate Mexico for five years, the May 5 victory became important in Mexico as a symbol of anti-interventionism and national pride.

May 5 also represents cohesion in the identity of both Mexican nationals here and Mexican-Americans, according to Jose Angel Pescador Osuna, Mexico’s consul in Los Angeles.

The battle “underscores what minorities have been able to accomplish and achieve under a superior power,” said Elba Bermudez, a Los Angeles telephone operator. Bermudez was born in Puebla, where she remembers that Cinco de Mayo is celebrated with much fanfare.

However, Cinco de Mayo is far less important in Mexico than Sept. 15 and 16, which mark the anniversary of the beginning of the fight for independence from Spain. Cinco de Mayo “would rank fifth among other celebrations” in Mexico,” Mexican anthropologist Jorge Cabrera said.

Cinco de Mayo was first observed in the Southwestern United States soon after 1862, historians said. Gen. Ignacio Zaragoza, who led the Mexican army to victory in Puebla, became a hero in Mexico and the Southwest. Zaragoza had been born in Texas when the territory belonged to Mexico.

As it is commemorated in this country today, Cinco de Mayo is a source of ethnic pride for many Mexican-Americans, said Miguel Dominguez, director of Mexican American Studies at California State University, Dominguez Hills.

Part of the secret of Cinco de Mayo’s success may be economic. “Don Dinero has caught on,” said Dominguez, and merchandisers have taken advantage of a cultural expression to push products.

The Los Angeles Unified School District, USC’s office of Civil and Community Relations and the Mexican Consulate try to foster a true understanding of the holiday through an annual essay contest that focuses on the significance of Cinco de Mayo.

At Hammel Street Elementary School in East Los Angeles, children are rehearsing Las Chiapanecas and other Mexican dances for a big program on May 4, Cinco de Mayo coordinator Emily Mori said.

Like many of his schoolmates at Hammel Street School, Angel Cardona, a sixth-grader whose mother is from Nicaragua, is excited about the event. Angel said he identifies with the holiday “because everybody else does too.”

Unaware of the frequent misunderstandings to which it is subjected, Cardona said the holiday has a special meaning for him. “It’s normal for us to celebrate it because we are Hispanic,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.