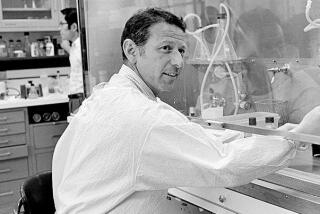

He May Be Crazy or He May Be a Hero--Only Time Will Tell : Science: Paul Marangos gave up the good life to pursue his dream of finding a drug that will lessen brain damage after strokes.

- Share via

Decide for yourself if Paul Marangos is nuts, then savethis story for 10 years and see who got the last laugh.

Marangos, 43, is dreaming of the future when his company, Neurotherapeutics, has successfully conceived, designed, developed, tested and produced a drug that will lessen brain damage after a stroke or head trauma.

The pursuit of this dream will disrupt his family life, expose him to personal financial thumbscrews, leave him responsible for $10 million in other people’s money, emotionally drain him and place his credibility as a scientist on the line.

He may end up famous and worth millions, a biotech hero. Or he may flop.

“People think I’m crazy,” Marangos says. “I tell them that, if I can’t get this rolling in a year, I’ll go to Plan B. But I haven’t given much thought about Plan B.”

Logic might have called for Marangos to remain as director of research at Gensia Pharmaceuticals, a respected Sorrento Valley company working on new cardiovascular medicines.

Company stock valued at about $250,000 was reserved in his name, and he was earning a six-figure income. He was living the good life in Encinitas with his wife, Maia, and their three children, ages 3 to 11.

But something had been gnawing at Marangos for most of his professional life, and he decided to do something about it before he got any older. He wanted to come up with a life-saving drug, and it meant walking away from routine and stepping into the professional abyss known as biotech start-up companies. Imagine the cartoon character who steps into the canyon void and somehow scrambles safely to the other side by madly spinning his feet. That’s what Marangos was trying to do.

“This was a sobering midlife decision,” he says.

Marangos got his Ph.D. in biochemistry from the University of Rhode Island in 1973, then specialized in neurobiology because of his interest in psychology and the brain.

From 1975 to 1988, he held a coveted position at the National Institutes of Health, the government’s medical research brain trust in Bethesda, Md. There he studied neurological diseases, overseeing eight laboratories and five postdoctoral researchers, as well as technicians and secretaries.

“I had unlimited access to research to pursue my ideas,” he said. “I figured I’d spend my career there.”

But, in 1988, he decided to go to work for a San Diego biotech company called Gensia because it was pursuing a line of work that captivated his interest.

“It was a start-up company and there was enormous excitement,” Marangos said. “And there was a certain element of risk. (Company President David) Hale told me we only had 1 1/2 years of our start-up money left, at our current growth and burn rate, but that didn’t bother me.”

Marangos’ wife of 22 years, Maia, recalled the decision to leave the National Institutes of Health for the private sector on the West Coast:

“Paul wanted to make a difference, to get a drug to market. He had been doing a great deal of research and was quite idealistic, but he wanted to do something more tangible with his life.”

“I had written 200 papers--and I was getting sick of it,” he said. “Only a few hundred people in the world could understand what I was writing about. The idea of helping to start a company thrilled me. And I wanted to help put something on this Earth that wasn’t here before me.”

In April, 1988, the family moved from the rural community of Germantown, Md., to Encinitas.

Those were heady days at Gensia, Marangos said. He was a big fish in a small pond, working toward a corporate agenda to develop a particular type of medicine.

In time, though, he realized that the drug he really wanted to help develop was not part of Gensia’s agenda.

“It’s not that they were working on bad drugs, or that mine was better. They were just different drugs, and Gensia couldn’t do both,” Marangos said. “It’s like asking someone who bought a Jaguar to buy a Mercedes, too. It’s just not in the budget.”

Last summer, he began to cut bait, meeting with an attorney who advised him on such issues as “intellectual property rights.” He wouldn’t be allowed to take Gensia’s own technology out the door, to avoid being at risk of developing a company to which Gensia could lay claim.

When he finally left Gensia to start his own company, on Oct. 15, there was both exhilaration and gripping fear. He forfeited his Gensia stock and abandoned his paycheck.

“I had never gone through such an emotional back-and-forth,” his wife said. “At first, it was like a great weight had been lifted off his shoulder. He was euphoric at having finally quit and being on his own.”

But she also wondered what it would mean to their security.

“I said to myself, ‘Boy, I was really getting to love this life, my house, Southern California.’ This was a lovely lifestyle. Now I was having visions of a for-sale sign in front of the house, and anticipating turmoil, of putting life on hold, of deciding not to buy this or that, or of putting off the kids’ piano lessons.

“And I remember when he quit, he told me, ‘OK, Maia, the mortgage has to be paid. I’ll transfer money out of savings.’ That’s when it starts hitting you, that this is scary.

“Here he was, at home every day, at the dining room table. The phone would ring and he’d say, ‘Shhhh!’ and talk on the phone and the whole house would have to fall silent.

“At dinner, when we’d normally talk about the kids and what’s going on in the world and in school and on the playground, he’d just jump in and say something like, ‘I’m going to give a call to so-and-so.’ And, when we’d be watching TV in bed at night and laughing in the middle of some comedian’s routine, he’d make some reference to the business.

“That first month, he was very distraught. He was hyperventilating. He was doing some second-guessing,” Maia said. “He’d say, ‘Do you realize what I’ve given up (at Gensia)? It’s not fair of me to do this to you and the kids.’ ”

Indeed, there were some adjustments. Marangos was at the office--a desk, telephone and conference table leased in an empty room at another research institute--seven days a week. “On Martin Luther King Day, the kids were out of school, and they thought we’d all be together. I got home at 7:30 that night. There was a little hurt,” he said.

They fired the housekeeper and the gardener. Vacations? “What’s a vacation?”

For months, Marangos even waffled on a name for his new company. At first he chose Regentech, for the regeneration technology he was employing. Later, he changed it to Neurotherapeutics because it more clearly reflects his specialty.

“There are no drug therapies for stroke,” he said. “But, in the past five years, we’ve been able to identify the targets. Now we can affect the damage that occurs after a stroke.”

A stroke is caused when a clot forms in an artery leading to the brain, starving brain tissue of blood. In the past five years, however, scientists have learned that, while the tissue immediately at the clot site is killed for lack of oxygen, larger amounts of brain tissue that are fed directly by that blocked artery continue to receive a small amount of blood from other arteries--through the back door, so to speak--and stay alive for a day or two.

The sharp reduction of oxygen to other parts of the brain results in the release of an excess--and toxic--amount of glutamatic acid, which is a neurotransmitter that helps complete the brain’s circuitry.

Marangos says he has identified three chemical compounds--one that he’s developed and two others synthesized by other researchers--that will inhibit the nerve cells from releasing too much of the acid when the blood flow to the brain is reduced.

“All three compounds will work, and it’s a matter of deciding which one will be best,” Marangos said. Already he has won the license to use the compounds developed by others, in exchange for an equity share of his company.

“Seventy to 80% of the damage occurs within two days after a stroke,” he explained. “It starts a chain reaction. We’re trying to reverse that mechanism.”

“The markets are enormous,” Marangos said. “There are a half-million strokes a year, and a million head trauma cases a year. If we can intervene within 12 hours, we can change that course. And we think these drugs may also be helpful for neurological degenerative disease, like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and Lou Gehrig’s disease.”

Marangos thinks he can get his proposed medicine to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for approval in seven years--a fast-track approval course because there are now no stroke medicines on the market.

“And then we’ll have a shot at saving 80,000 lives a year,” he said.

Developing the science is, for now, the lesser of his challenges, Marangos said. He just recently hired a chief executive officer to run the company--Bob Fildes, former president of Cetus Corp., a large pharmaceutical company in the San Francisco Bay Area. And he’s lining up a scientific advisory board. Altogether, he said, 19 people have associated themselves with Neurotherapeutics so far, hoping for a piece of the action.

“I’m recruiting by excitement,” Marangos said. “And it’s surprising to see how many people have that entrepreneurial spirit.”

Marangos is now up against his biggest challenge: getting $10 million in venture capital to fund the company for 2 1/2 years.

“Less than a third of these companies get funded,” he acknowledged. “This is a high-risk venture. A lot of VCs (venture capitalists) tell me I’ve got good science. But I’m still waiting for the money.”

Hale, the president of Gensia, has offered his former research director encouraging words.

“I know it’s taking him longer (to get funded) than he anticipated,” Hale said. “I told him that sometimes it will take a long time. It took the two founders of Gensia about 10 months, after the time they were first introduced to the VCs, to get funded.”

Marangos said that, in several months, he will have to decide whether to cut bait and get a job somewhere else, if his dream can’t be transformed into currency. There’s only so much money in savings, after all.

“You’ve got to be half-crazy to do this. Logical people will say this doesn’t make sense,” Marangos said. “But, if you don’t try, part of you will always say, ‘Why didn’t you try?’

“I never want to look back and ask myself that.”