Doing Wonders for Rock

- Share via

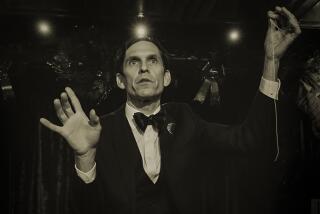

Franz Harary levitated Michael Jackson. He made Bone, Thuggs & Harmony appear on stage. He impaled a girl on Alice Cooper’s microphone stand.

But at the moment, he’s having a little trouble with call waiting.

Just a minute, he says from a New Orleans hotel room. Give me your number. I might lose you.

Not what you want to hear from a man who specializes in making rock stars appear and disappear.

Harary, an illusionist who has headlined shows in Las Vegas and Atlantic City, also has carved out a large and lucrative niche adding touches of magic to live concerts. In fact, when the band Styx appears--suddenly in a puff of smoke--on the Universal Amphitheatre’s stage tonight, it will be as a result of Harary’s engineering.

Raised mostly in Ann Arbor, Mich., Harary got his first taste of magic from a Cap’n Crunch box. He was amazed that he could fool grown-ups with sleight of hand.

“I found myself intrigued by not only how these tricks worked, but why they worked--the psychology of it,” he says. Even now, big stunts like making Harry Houdini’s character disappear in the musical “Ragtime”--a trick he also designed--is 80% psychology and 20% technology, he says. “If you understand how people think, reason and reach conclusions about everyday events, then ultimately you can manipulate them.”

Even though he was enrolled at another college, the University of Michigan marching band started using some of Harary’s tricks in halftime shows. He made the trumpet section disappear; he levitated a woman above the 50 yard line. In short, he got used to working in a stadium with 360-degree visibility.

His move into the rock concert arena, though, had more to do with chutzpah than experience.

After Michael Jackson was burned in a mishap on the set of a Pepsi commercial, Harary called Jackson’s lawyer, whose name he’d heard on the news. The lawyer told him to call someone else, who told him to call someone else. Eventually, he reached the producer of Jackson’s Victory tour.

“The truth is, I was totally out of my league. But I sent him a videotape of what I’d done for all those halftime shows,” he says. “I said, ‘I do this for marching bands, I do this in stadiums, I can design magic for your show.’ ”

And then, at age 21, he was hired. He left college, moved to L.A. and became the rock ‘n’ roll magician. Since then, he’s designed for everyone from Kool & the Gang to Tha Dogg Pound.

John Troxtel, a live-concert designer who’s worked with Harary for 11 years, says: “If you want magic in your rock concert, he’s the guy you call.” It’s not just his expertise in the field but the fact that he puts performers at ease. “He’s able to teach these artists what to do and convince them that, yes, you can do that.”

Magic stunts have become increasingly popular in rock concerts because musicians want to deliver a show comparable to what they can do in videos.

But contemporary audiences have also become a little jaded by visual effects in movies and TV. And Harary is the first to admit that what he does isn’t so different from a special effect. “If a building floats up into the air, it’s a special effect,” Harary says. “If I’m standing there pointing, it’s magic.”

In the magic community, says fellow magician Seth Yudof, illusionists can get the rap of being little more than theatrical finger-pointers. In fact, illusions are bought and sold by magicians all the time, at prices from $3,000 to $50,000.

But Harary designs all his own tricks--from “teleporting” cars from Detroit to Los Angeles for a car show, to stretching his arm through three televisions. So most of the hard work is on the front end, Yudof says. “Franz designs more magic in a year than most people design in a lifetime.”

For the musical “Ragtime,” now playing at the Shubert Theatre, Harary actually had to tone down one illusion. In it, legendary escape artist Harry Houdini disappears from an exploding crate. The wooden box, suspended above the stage, looked completely out of control, he says, which pulled the audience too far out of the play.

While the escape fits our collective memory of Houdini, Harary says, it really is nothing like what the turn-of-the-century escapist did. Houdini’s acts were long and drawn out; he could spend an hour trying to get out of a crate. “I had to design an illusion that looked like something that Houdini might have done,” he says, “but with all the psychology that would work for a 21st century audience with a very short attention span.”

His own show, “Hypereality,” is designed for the remote-control generation: quick tricks, flashy lights, lots of TV monitors. It requires 26 people and 25 tons of equipment to stage. Harary could probably tour for the rest of his life with the 250 illusions he owns. But he gets bored. So he’s constantly building new illusions--at a cost of more than $50,000 apiece. “I would rather be excited about what I’m doing than be rich,” he says.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.