Hank Garland, 74; Guitarist Bridged Country, Rock, Jazz

- Share via

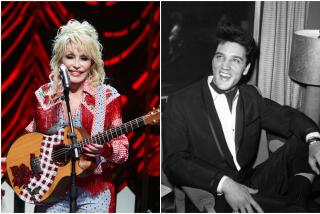

Hank “Sugarfoot” Garland, a country, rock and jazz guitarist known for his technical expertise and innovations such as the memorable musical riff on Elvis Presley’s recording “Little Sister,” has died. He was 74.

Garland, who also performed with the Everly Brothers, Roy Orbison, Conway Twitty, George Jones and Gary Burton, died Monday in Orange Park, Fla., of a staph infection.

Presley had run through “Little Sister” twice in a Nashville recording studio by 2:30 on the morning of June 16, 1961, and the song wasn’t working. The legendary singer suddenly stopped the music and pleaded, “Hank, help me out of this one.”

Garland, known for his spontaneous bursts of music, instantly came up with the eight-note riff that lifted the recording from humdrum to dazzling and helped make it a hit.

Wolf Marshall, author of “The Guitars of Elvis,” described Garland, who worked with Presley for four years, as “a quintessential Nashville studio guitarist.” Presley called Garland “one of the finest guitar players anywhere in the world.”

Shortly after the “Little Sister” recording session, however, Garland was thrown from his station wagon when it overturned in a crash. He was 31.

Garland’s brother Billy calls the crash attempted murder, claiming that enemies in the Nashville recording scene had made threats, and that shots were fired before the wreck.

After being in a coma for months, Garland was given 100 shock treatments that robbed him of his short-term memory. His health was weakened by a series of seizures and strokes.

He relearned to walk, talk and play guitar. But he never regained his coordination or musical memory, and his brilliant riffs, solos and innovative fingering drifted into history.

Born Walter Louis Garland in Cowpens, S.C., he got his first guitar at the age of 4 -- an instrument made by his mother, Odessia, from a metal lard can lid, a stick and strings plucked from screen wire. At 6, he graduated to a used Encore guitar that his father bought for $6.50 and played it until his fingers bled.

By 12, he was performing on a Spartanburg, S.C., radio station and two years later met Paul Howard, who had a Grand Ole Opry band, in a local music store. The boy impressed Howard and he followed the bandleader to Nashville, where Howard let him play a boogie-woogie tune at the Grand Ole Opry.

The audience loved the young musician, and Howard invited him to join his Arkansas Cotton Pickers, billing him as “The Baby Cotton Picker.” The work was interrupted by child labor laws, but when he turned 16, Garland rejoined the band and also played with the Cowboy Copas.

He was still in his teens when he made a 1949 recording of “Sugarfoot Rag,” a rigorous guitar romp he wrote as a finger exercise, and earned the nickname Sugarfoot.

The new Nashville virtuoso was one of the first to play country music on electric guitar, and helped move the genre from its acoustic roots to an electric sound. He toured with Eddy Arnold and recorded with major Nashville artists, becoming an industry favorite.

Garland joined guitarist Chet Atkins on Don Gibson’s “Sea of Heartbreak,” crafted the introduction for Patsy Cline’s “I Fall to Pieces,” played the blazing solo on Patti Page’s “Just Because” with the singer heard urging “Go, Hank!” and played lead guitar on the Everlys’ “Bye, Bye Love” and “Wake Up Little Susie.”

The rockabilly and country guitarist also won respect for his jazz efforts, playing at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960 and recording Nashville’s first jazz album, “Jazz Winds From a New Direction.” The album cover pictured Garland at the top of his game -- smiling from his convertible with four Gibson guitars.

But the accident ended the career.

Without the crash, Marshall told the Florida Times-Union in April, Garland’s career would have been “an amazing thing.”

“It’s pretty rare that someone could play jazz at that level, play really effective rock ‘n’ roll, then play country like that,” he said. “He would have made more jazz records, and since he was just at the beginning of his career, he would have been as big a legend as Wes Montgomery or Tal Farlow or even someone we look back at, like Django Reinhardt.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.