A special role in the community: Racism pushed Black women to succeed

- Share via

This story originally ran in 1982 as part of the “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” series. We have preserved the original text in order to provide an accurate account of the work in print.

Even during the uncertainties of the Depression, Georgia farm girl Jo Ann Robinson always knew one thing — she would follow her 11 brothers and sisters to college.

For accountant Adrienne Johnson, there is one outstanding memory — Saturday afternoon talks with her father during which he cajoled her into doing better in school, settling down and making definite career plans.

Just as clear is Judith Bowman’s commitment to balance a corporate legal career with pro bono work for the betterment of the black community.

These three women — and tens of thousands like them — are representative of educated black women who for generations have been taking leadership positions within the black community. Whites often erroneously labeled them as “superwomen,” but they are not. They are women who are just living up to the standards that the black community set for them.

Oddly, these women are products of institutional racism.

It may be hard to imagine how racism of any kind could produce three such success stories. But these women grew up in a time when the traditional job market was virtually closed to black females, and the only way to escape working as a domestic was to enter college and prepare for a professional career, most often in the black community. Parents of these women played a crucial role in pushing them in that direction.

The thinking went: If you do not want your daughter to become a maid in the white man’s house, make sure she goes to school so she can become a nurse. Because she cannot get a job in the white community as a secretary or a sales clerk, push her through college so she can become a teacher.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

These concerned parents had to focus more on their daughters because they knew that if their sons did not complete college and enter professions, they could easily get jobs on an assembly line or in a warehouse. Black women did not have these blue-collar alternatives open to them.

Thus, the daughters grew up to take a special place in the black community. They were the teachers in segregated classrooms who not only taught the “Three Rs” but also spent endless hours prodding their students onto higher achievements and served as role models to another generation of young black women.

They were “Sisters of the Church,” the ones who made sure this vital hub of the black community functioned smoothly. They worked in public health departments bringing medical care to the shanties of the Delta region.

They helped black people in registering to vote for the first time, they occupied college administrators’ offices while making “non-negotiable demands.” Today they are slowly moving into mainstream corporate life.

The community that created these women came to depend on them and, in that dependence, lost some of the sexism found in the wider community.

Fewer barriers

For blacks, if a woman was the best person to run a political campaign, be dean of a law school, publish a newspaper or represent an area in the House of Representatives, there were fewer barriers to stop her from doing it.

These black women did not even exist in the minds of the majority community. When one of these black women finally did break through to the white consciousness, whites erroneously labeled her a “superwoman.”

This label, according to sociologists, is yet another example of white society misinterpreting the interrelationships of black Americans.

“To call these women superwomen is to say they are not human,” said Elizabeth Higginbotham, an assistant professor of urban sociology at Columbia University.

Viewed as a group, these women are capable, but they are still very dependent on their nuclear and extended families for moral support, sociologists say.

In addition, for most there is a period of self-isolation during their adolescence. And for a variety of reasons, many delay marriage until they are in their late 20s or early 30s.

A prevalent myth in both the white and black communities is that black women have an easier time than black men in the majority society’s working world. Yet, according to the Department of Labor, the median income for black men is higher than it is for black women with comparable educations. Moreover, Equal Employment Opportunity commission records show that about 60% of job discrimination complaints come from black women.

Still, affirmative action is the other reason these women are gaining recognition, said Eleanor Engram, a San Jose consultant and expert on black family life.

“Mainstream society sees her more now because there are more mainstream roles open to her. Many whites are astounded that these women are so capable. What they don’t understand is that these women have had several generations of capable women to pattern themselves after,” Engram said.

High value of education

Like so many of the black women in this group, Jo Ann Robinson came from a family that placed a high value on education.

“My mother stressed education and going to college. That was just the expected thing to do,” said Robinson, a community activist and former college professor who recently retired after teaching in Los Angeles public schools for 16 years.

“It just never occurred to me that I wouldn’t follow the other 11 children to college,” she added.

Like so many other college-educated black women of her generation, Robinson became a teacher — one of the few careers that black women of that era could enter with some assurance that there would be jobs for them when they graduated from college.

Columbia’s Higginbotham said black women of this generation often chose such occupations as teaching or library work in order to have jobs that would allow them to reduce their participation when they had children.

In 1954, when Rosa Parks was arrested in Montgomery, Ala., for refusing to give up her seat on a public bus to a white man, Robinson was teaching at Alabama State University and was a leader of the Women’s Political Council, an organization of black educators who wanted to change the segregated seating policy enforced on Montgomery buses.

The night of Parks’ arrest, Robinson secretly used university mimeograph machines to print 65,000 leaflets that encouraged Montgomery’s black community to start a boycott of the public transit system at the end of the week.

“The leaders [of the boycott] became targets for retaliation,” Robinson recalled. “The front windows of my home were blasted out and acid was thrown on my new car. Threatening telephone calls [during] the night were common occurrences for all of us.”

Commitment to working for social justice for blacks is one of the most common traits these women share, researchers say. At the turn of the century it was called working “to uplift the race.” In the 1950s, the call was “We Shall Overcome” and by the 1960s, the slogan had changed to “Power to the People.”

“One thing you can say about these women is that they never took the financial security and social standing they gained as a way to leave the community. They stayed and worked for better conditions for all black people,” said Cheryl Brenda Leggon, who is doing research work on black women at the University of Chicago.

Higginbotham believes that many of these women were taught in the home that they had a duty to help other black people. In addition, Higginbotham said, these women held the belief that their work should relate to social concerns since the careers of many of their parents, especially their fathers, were involved in community service.

The bond between father and daughter greatly influenced the success of these women, researchers have found. Many of them credit their fathers with giving them the most encouragement in their attempts to reach certain goals.

“My father always took time to talk to me about what I wanted to do in the future, what I wanted to be and how I was going to do it,” said Adrienne Johnson, who works in Los Angeles with one of the Big Eight accounting firms. “Those talks were no big deal, but you know, I still remember them. I guess they must have meant something special to me.”

If the fathers of these women encouraged their daughters, their mothers played an equally important role. It was the mothers who provided the role model of a woman handling a career outside of the home while running a household who gave their daughters the self-confidence that they could do it too.

“When I was growing up, mothers always held jobs outside the home. There was nothing unusual about that,” Johnson said.

Everyone pitched in

“Fathers always helped with the household chores,” she added. “For the house to run smoothly, everybody had to pitch in.”

This type of close-knit family often comes to the aid of these women when, researchers say, they go through periods of self-imposed isolation from their peer groups. In some instances this withdrawal comes as a result of the young women finding themselves racially isolated in a new environment such as college or a new job. For Johnson, the loneliness and the isolation came during her first year at Brandeis University.

“The whole scene back there was different. The way people dressed, what they talked about and the weather. For a black girl from Inglewood, it was a drastic change,” she recalled. “I was so unhappy, but the family was great. They called me, wrote me, really made me feel that I wasn’t as alone as I felt.”

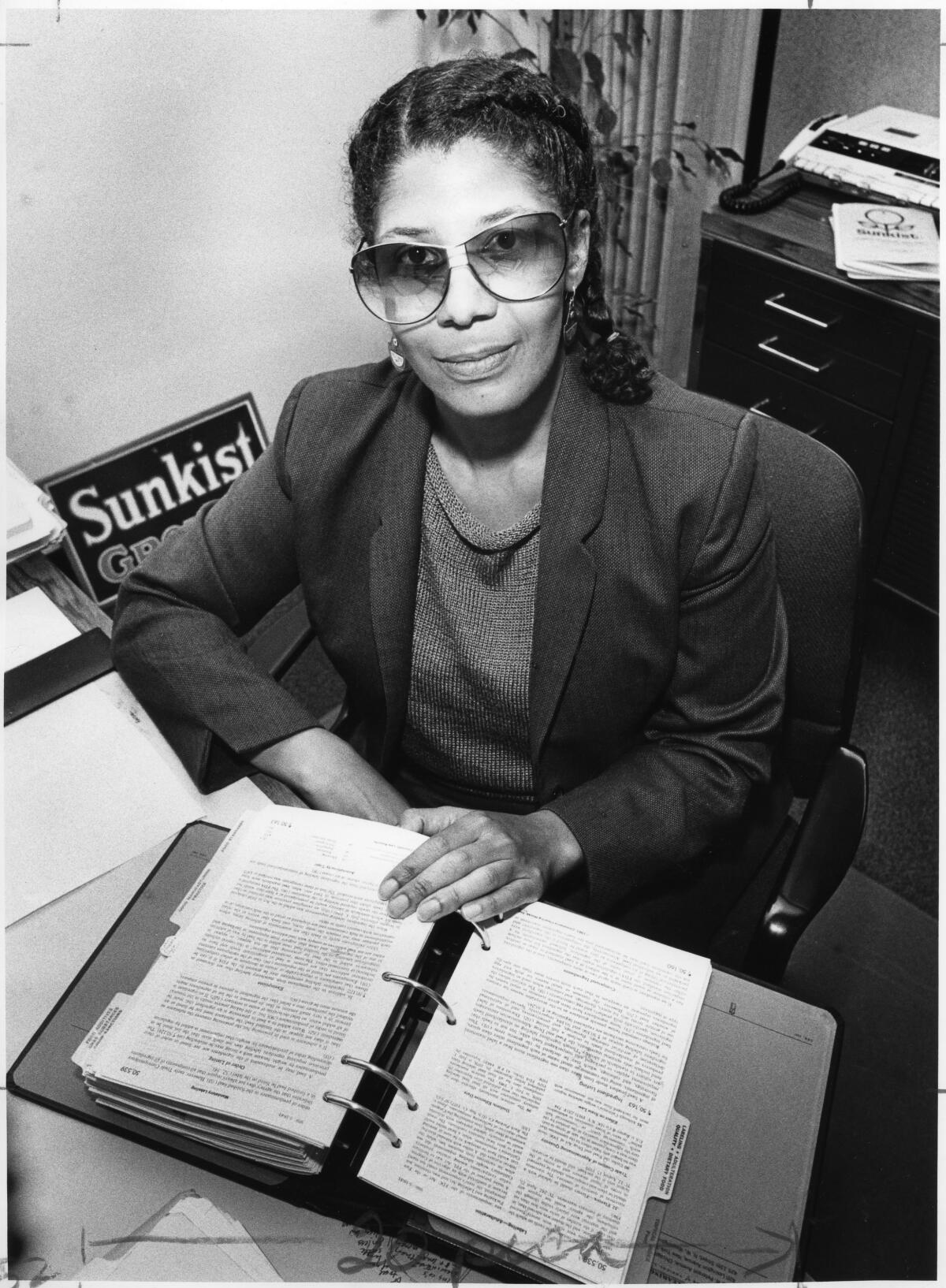

Like Johnson, Judith Bowman is part of a new generation of black women who are entering the once lily-white arenas. Bowman, a staff attorney for Sunkist Growers Inc., starred her law career at a legal clinic in the Crenshaw area that she and a group of fellow UCLA Law School graduates opened.

“We went into the project with a lot of high ideals. We thought we could make some breakthroughs,” Bowman said. “I have continued to donate free time to help demystify the law,” Bowman said. “Recently I participated in the Black Women Lawyers tutorial program to help repeat Bar candidates.”

According to Ronald Brown, a San Francisco psychologist, this generation of intensely career-oriented black women still has the desire for community involvement, but the types of organizations the women are involved with have changed.

Different interests

Instead of sororities, social clubs and grassroot political groups, such organizations as the Black Bankers Assn. and the Black MBA Assn. are receiving greater attention from the women.

“Instead of wanting to uplift the black community, now these women want to make sure that other blacks have the same opportunities as they did to participate in these careers,” Brown said.

Brown has seen other changes in this new generation of black women corporate pioneers. For one thing, he said, they are more involved with their careers, much to the surprise and sometimes consternation of their families.

Bowman, for instance, said her family is resigned to the fact that she is over 30 and is not married, does not have children and leads a different lifestyle than they anticipated.

Brown adds that as more black women move into corporate settings, they are discovering problems their mothers never faced.

They have difficulty in deciding which is the appropriate action to take in certain business situations, and many believe that they are left out of informal office communication lines.

“White women often have an easier time tapping into these networks than black women because black women cannot fall back on cultural and class similarities,” Brown said.

Another problem is that many big companies do not see black women as potential leaders, Brown said. While the media has drawn a clear image of white career women, it has not created a similar picture of black career women.

Leadership potential ignored

“I worked on a case where a black woman was bypassed for a supervisorial position because her white bosses didn’t believe she had leadership potential,” Brown said.

“What they didn’t realize was that on weekends she was an officer in the National Guard and in fact was used to commanding large numbers of of men and women. Her superiors just couldn’t visualize her in a leadership role.”

This dilemma — being incorrectly judged by white society — is something Higginbotham said happens to most black women.

They are “damned if they do and damned if they don’t. Poor black women are blamed for their situation and professional black women are never given credit for their accomplishments.”