Black athletes: Chasing the elusive goal of the pros

- Share via

This story originally ran in 1982 as part of the “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” series. We have preserved the original text in order to provide an accurate account of the work in print.

As the buzzer sounded, the scoreboard in the packed Los Angeles Sports Arena told the story.

Verbum Dei 60, Pasadena 45

For the third consecutive year, Verbum Dei High School in Watts had won the 4-A Division California Interscholastic Federation basketball championship for Southern California.

In a mad, exhilarating rush, 13 jubilant players leaped into each others arms and thrust their forefingers triumphantly into the air to punctuate their supremacy.

Theirs was an outstanding team: Three of the players were all-Americans and two would be named CIF player of the year. Others would be named all-CIF, or similarly honored. College recruiters and scouts in the stands relished the prospects.

On that glorious night, the sports futures of these 13 young men shone brightly. If there were ever a group of players destined for the professional careers that they all so desperately wanted, surely, they believed, it was them.

In fact, for all save one, they were in the autumn of their careers. Like so many others, however, they failed to realize it.

For countless black youths like those on the 1972-73 Verbum Dei basketball team, a career in professional sports is the substance of sweat-soaked dreams, the tantalizing brass ring dangling just beyond their reach. It is a vision born in the first faint light of celebrity, grounded in a quest for identity and reinforced by glowing media images of black athletes.

Positive Image

“The one consistent exception to the negative images presented of blacks in the media has been the black male athlete,” University of California, Berkeley sociologist Harry Edwards said. “The message, though subtle, is clear: If you are black and want respect, justice and equality of opportunity and reward from white America, become an outstanding athlete.”

But that message is a cruel hoax for all but a precious few. If the odds of ever having a professional sports career were displayed on a tote board, no one would take them. Thousands and thousands to one against making the pros. Statistically, these young men would be 15 times more likely to become doctors, 25 times more likely to become engineers.

“A high school student stands a better chance of being hit by a meteorite than getting into the pros,” said Allen Sack, director of the New York-based Center for Athletes’ Rights and Education.

The tragedy is that in this preoccupation with sports, black youths frequently fail to get the two things they most need — an education and a degree.

The pro myth thrives on an irresistible vision. There are three pots of gold at the end of the rainbow: the National Basketball Assn., National Football League and major league baseball.

The sports pages are full of salaries to be made — exciting, stupefying sums — on the average. $185,000 a year in the NBA, $149,500 for major league baseball and $78,600 a year in the NFL.

And as the representation of blacks in professional sports increases, the lure grows stronger.

Thus, spurred on by a misguided notion of black athletic supremacy and served a daily diet of pro athletes as models, black youths are disproportionately drawn to the dream of status and riches that a professional career can offer.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

It begins early on the asphalt courts at 62nd Street and Denker Avenue, the sandlots of Compton and on the baseball diamonds in South-Central Los Angeles, and from there it escalates.

“As soon as someone discovers that one child has a greater athletic potential than his peers — usually in junior high, if not before — that child is effectively separated from his peers,” Edwards said. “He becomes something special.”

So it was for the members of Verbum Dei’s championship squad. By the time they had reached junior high, their talents had become so apparent that they were practically adopted by surrogate fathers — coaches who spent hours teaching them the finer points of basketball, who invited them over for weekends and generally watched over their athletic progress.

The nurturing became part of a championship era.

Beginning in 1969, Verbum Dei, an all-boys Catholic school sitting hard by the Southern Pacific railroad tracks on 15 drab acres previously occupied by a steel plant, won six consecutive CIF basketball titles, including an unprecedented four straight in the top 4-A Division.

Before long, Verbum Dei had become known as the UCLA of Southern California prep basketball.

On the 1972-73 team were forwards Allen Hollis and Michael Pyles, Lewis Brown at center and Ivory Tackwood and Eddie Williams at guards. In reserve were guards Michael Lewis, Roy Hamilton and Willie Turner, center Michael Richards and forwards David Greenwood, Ken Ross, Fred Shaw and Reggie Bowie.

As they left high school, all 13 envisioning professional careers, they encountered the first hurdle — making the varsity team at a major college. The odds against them were monumental.

Nationally, more than half a million high school boys play varsity basketball annually, a million play football and 400,000 play baseball, according to the National Federation of State High School Assns.

Just two of every 100 of them will ever play basketball for a major college, and only four in 100 will play football and baseball.

In other words, more than 95% of the boys who play one of the three major varsity sports in high school will never compete in those sports for a major college.

As stiff as the odds are, they are even stiffer for blacks. Nationwide, it is estimated that only 6% of the college athletic scholarships go to black students.

Rapidly Fading Memories

For thousands of black high school athletes who never reach college, academic standards and their own obsession with sports often combine to send them out into the world with little more than memories of rapidly fading celebrity — and almost nothing resembling a high school education.

Both the CIF and the Los Angeles Unified School District grade requirements for a student to continue in sports are so minimal as to render many players academic cripples. A student is allowed to make four Ds and two Fs during a reporting period and still be eligible to play. And because eligibility is determined at the midpoint of a semester, a student can actually fail a semester and still play on a team.

At Dorsey High School, for example, a study discovered that 20% of the players in spring sports this year had two or more Ds or one or more Fs on their first report card of the spring semester. Alarmed Dorsey officials have initiated a program requiring failing athletes to attend tutorial sessions rather than team practice.

“The eligibility requirement is so minimal that it does not at all constitute any encouragement for an athlete to be a good student,” said George McKenna, principal of Washington High School in Los Angeles.

Consequently, three of every 10 athletes in Los Angeles high schools who are offered athletic scholarships probably will be unable to accept them because of poor grades, according to a study of the city’s athletes by the Chicago-based Athletes for Better Education.

In that one important respect, the Verbum Dei team of 1972-73 was atypical. All 13 went to college, Verbum Dei is an exceptional school. Solid academics accounts for 80% of its seniors going to college; 60% earn degrees. A Verbum Dei graduate was a Rhodes scholar.

Landed Full Scholarships

Pyles and Williams received full basketball scholarships to UC Riverside. Tackwood went to California State University, Hayward. Greenwood, a CIF player of the year and high school all-American, and Hamilton, also an all-American, landed scholarships to UCLA. Bowie went to Central University in Iowa on a basketball scholarship.

Brown, another high school all-American and the only player in the history of the CIF to be twice named CIF player of the year, enrolled at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Hollis went to Cal State Long Beach while Ross headed to Compton Community College.

For others, the door opened more slowly. Richards was unable to accept a number of basketball scholarships because of poor grades. He had to go to El Camino Community College to improve them before transferring to Cal State Long Beach and later UCLA.

Lewis, hampered because he quit the team during his senior year, wound up at Southwest Community College instead of a major school, a serious setback to his pro career aspirations.

Shaw thought he was going to Pepperdine’s Malibu campus, where he could showcase his skills for the pro scouts. Three days before school opened, he received a letter saying the school could not provide financial aid. He went to Pepperdine’s downtown campus, arranged for emergency aid and was told by the school coach to play some basketball there with the promise that he would be able to transfer to Malibu.

Willie Turner received a letter he thought was a firm scholarship offer to the University of Hawaii, only to learn later that it was simply a letter expressing a recruiter’s interest. Over the summer after graduation he unsuccessfully sought scholarships at other schools and finally settled on Riverside City College. He played well enough there to earn a football scholarship at the University of Nevada, Reno, where he became a cornerback.

In the last 20 years, colleges have allowed their “money” sports — football and basketball — to become farm systems for the professional leagues, sports observers say. In so doing, these observers contend, colleges have permitted their athletes to embrace a dangerous myth: that attending college with the sole aim of making the pros is a sensible strategy.

In 1979, for example, the University of Miami produced a four-color recruiting poster captioned “A Pipeline to the Pros” that included pictures of those Hurricane players who had “made it.” And when once asked why the NBA does not have a farm system, President and General Manager Red Auerbach of the NBA’s Boston Celtics replied incredulously, “What for? We have the greatest farm system in the world — the colleges.”

High school athletes, many of them scholastically handicapped, are thus invited to college to pursue an impossible dream: to become one of the small number of college players (less than 2%) who make the NFL and NBA.

Immediately they find balancing athletics and academics a tough act indeed. The conflict between the two is such that many athletes, with the explicit cooperation of the institutions, become nothing more than “eligibility majors,” taking snap courses that keep them eligible to play sports but do not satisfy graduation requirements.

A full-time college student is required to take 12 hours of instruction, not a particularly heavy load under normal conditions. But a football player’s typical day goes something like this: classes 8 to 12, team meeting 1 to 2:30, practice 3 to 5 or 5:30, dinner with the team 5:30 to 7. And on Saturdays, there are games.

“By the time a football player is in college, he is already putting more time in on his athletic career than he would be putting in on a full-time job,” Edwards said. “Basketball and baseball are only slightly less demanding.”

Anxious to keep the athletes available to fill their huge stadiums and arenas, some schools often funnel them into classes that lead nowhere, or even give them credit for classes they did not take — thus depriving them of an education and the degree that goes along with it.

This is part of the reason why only 25% of pro football players, 30% of pro basketball players and 40% of pro baseball players have college degrees, according to a study by Edwards, the UC Berkeley sociologist.

So rampant is the system that between November, 1979, and April, 1980, there were 13 separate incidents at major institutions of athletes receiving credit for classes they had not attended. More than 60 students were involved: more than 30 of them attended USC or UCLA. Six of the 13 incidents involved California schools.

Some are cases like Billy Don Jackson, a black youth who had trouble reading anything more difficult than “see Spot run,” but was admitted on a football scholarship to UCLA, where the typical student is among the top 12.5% of his high school class.

When it was discovered that Jackson could not read, his advisers ushered him into classes described by his classmates as “Mickey Mouse” — courses that did not require reading.

Jackson’s plight is not dissimilar to that of many black student-athletes. Seven black former athletes at Cal State Los Angeles are suing the school, its president and their three former coaches for $14 million. They claim breach of contract and misrepresentation — that they were promised basketball scholarships and got instead student loans for which they were billed after their eligibility had expired. They also claim they did not receive anything remotely resembling a college education.

Randy Echols, the group’s spokesman, says that the three Cal State coaches did all the classroom “arranging,” that there were athletes on the dean’s list who read at the third-grade level, and that his own arranged schedule included water polo, badminton and theory of movement. Echols, a B-student and president of the student body at Verbum Dei in 1971, said he dropped such courses “behind the coaches’ backs” so he could enroll in economics, English, speech and other more worthwhile classes.

“Colleges are supposedly offering an academic program to athletes in return for their athletic services,” said Sack of the Center for Athletes’ Rights and Education. “But all too often, athletes end up without an education.”

The combination of forces ultimately takes its toll, sending thousands of college athletes packing before their senior year. Of those that remain, graduation is the exception rather than the rule. In a study for the American Council on Education, Roscoe C. Brown Jr., president of Bronx Community College, found that at one school only 46% of black athletes who were seniors graduated and that at another college “only 12 of 46 black athletes got their degrees.”

The Verbum Dei championship team was no different.

Ivory Tackwood became academically ineligible to play basketball during his fourth year at Cal State Hayward as he tried to balance athletics, academics and a job. He left school at the end of the year — a year away from graduation.

“I didn’t study the way I should have,” he said. “ I went to summer school, but I was working a job 10 hours a day, six days a week. It got kind of hectic. Maybe I didn’t listen the way I should have. But I was by myself. It was the first time I had left home. It was kind of scary.”

Fred Shaw never got that transfer to Pepperdine’s Malibu campus and left school after his second year. Reggie Bowie left Central University in Iowa after his freshman year, finding the adjustment too difficult. Allen Hollis quit Cal State Long Beach in his senior year after he found he could no longer balance running track and working part time to support his wife and baby.

Michael Lewis played basketball for two years at Southwest Community College before a broken ankle suffered during a game ended his basketball and college careers. Ken Ross quit Compton Community College after a year and joined the Navy, and Lewis Brown left Nevada Las Vegas his senior year.

Williams transferred on a basketball scholarship to Portland State, a bigger school at which he could get more exposure. Near the end of the season, however, he suffered a broken ankle in practice. His doctor advised him that he could not play while the ankle healed. Traumatized by the prospect, he dropped out of school. During the year he was off, he reinjured his ankle and never returned to Portland State.

During his first year at UC Riverside, Michael Pyles also had academic problems.

“Coach stressed getting an education,” Pyles said, “but when you had a problem with your studies, he would just tell you not to worry about it.

Made the Dean’s List

“Coach would say, ‘I’ll talk to the professor about it.’ But I never took him up on his offer because my parents had taught me to get my education on my own and not to cheat because the people who help you end up possessing you.”

Pyles studied hard, sought tutoring and eventually made the dean’s list. Even with the improved grades, however, it appeared for a while that he would not graduate with his class. After suffering a knee injury during his junior year, his coach wanted to keep him in school an extra year so he could completely recover and play another season.

“But I wanted to graduate with my friends,” Pyles said. “I knew it would end my chances to make it to the pros, but professional basketball is not the only thing in life.”

By now, the 1972-73 CIF championship team had learned that the selection process grinds swift and fine. Eight of the 13 had left college. And for most of those who remained, the dream of a professional sports career that once burned so brightly had begun to fade.

Richards had made it to UCLA, but never made the varsity team. Pyles decided to graduate although he knew it would end the prospect of a pro career, and Turner, finishing up a degree in health education administration, realized that he would never have a career in professional football.

Only Greenwood and Hamilton, all-Americans at UCLA, remained strong contenders for the pros.

If the number of students making it from high school to major college sports are slim, those going from college to the professional ranks are almost non-existent. About 4,000 players complete their college basketball careers each year. Approximately 200 get drafted by the 22 NBA teams. About 50 actually make the teams.

Careers Short

For those select few who do make it to the pros, average careers are woefully short. Fixed in the public consciousness is the image of the 15-year veteran who is a good bet to make it to the Hall of Fame.

However, an average pro football player, who turns 22 during his rookie year, ends his career just before his 26th birthday in basketball and just after his 26th birthday in football. Baseball players, who often go directly to the pros from high school, play only an average of 5 ½ years.

Greenwood was selected in the college draft by the NBA’s Chicago Bulls, Hamilton by the Detroit Pistons — both in the first round.

Greenwood signed a lucrative contract and broke into the Bulls’ starting lineup, where he remains. He had made it. Hamilton signed for $450,000 over three years, but after just over a year with the Pistons, he was released. No other NBA team picked him up.

Thus, the odyssey was complete.

The exceptional team from the exceptional school had traveled the treacherous road traversed annually by thousands of black youths. And it had taken its losses.

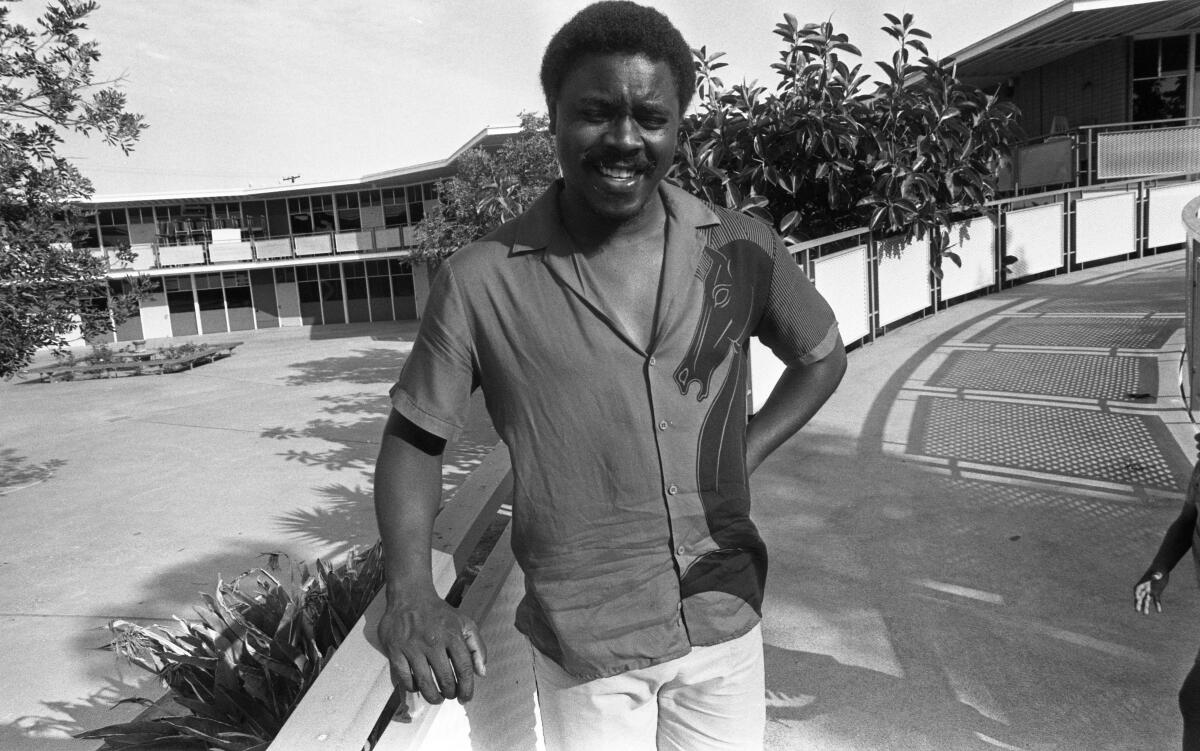

Pyles was graduated from Riverside and is now a disability evaluator for the state of California. Tackwood, who spent a year and a half playing minor league basketball after quitting Cal State Hayward, has worked as a security guard at a Compton elementary school for the last two years.

Richards earned a degree in law enforcement at UCLA. A private investigator for five years, he has been a tool and die maker at an aerospace firm for the last six months.

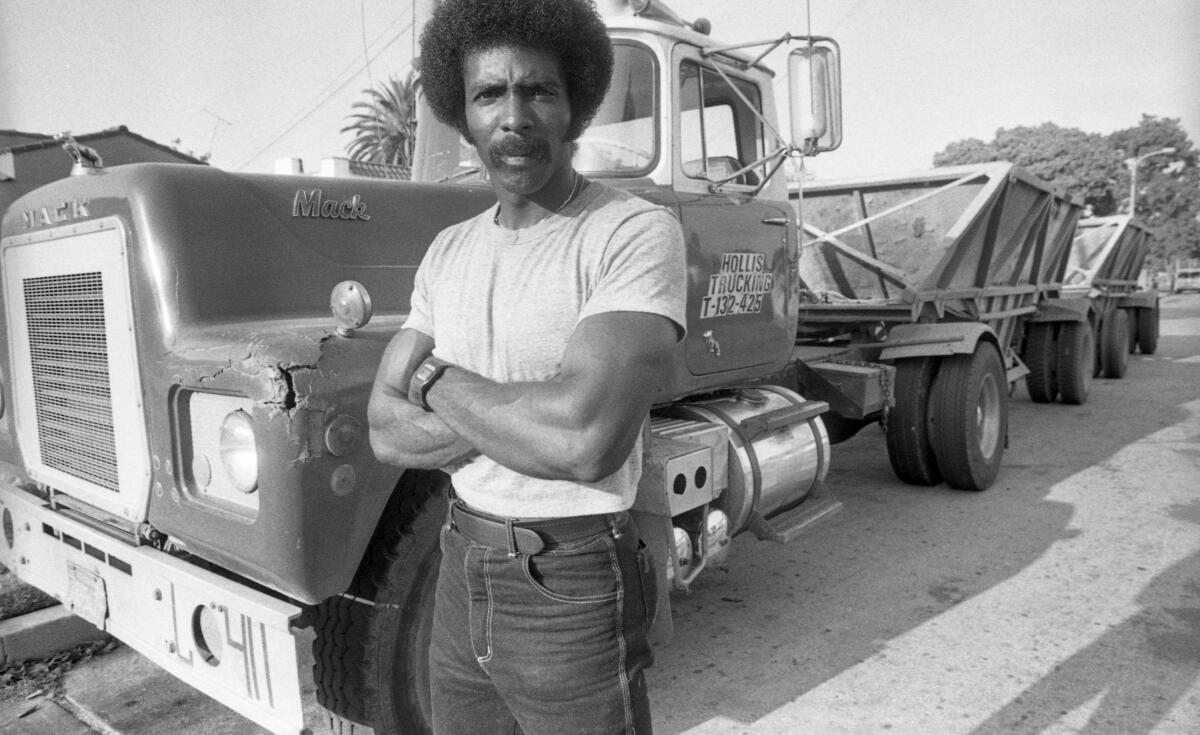

Hollis is now a driver for his family’s trucking company. Lewis, who suffered the career-ending injury, for the last five years has worked as a traffic coordinator at an aerospace company.

Ross, following his stint in the Navy, worked a variety of odd jobs, mainly as a heavy equipment operator. For the last year he has been unemployed.

Deputy, Blackjack Dealer

Shaw for the last two years has been a Los Angeles County deputy sheriff. Turner earned a degree in health education administration, but for the last five years has been a blackjack dealer at a Reno casino.

Bowie spent several years working on the Alaskan oil pipeline after leaving school following his freshman year and now coordinates deliveries and pickups for a Whittier trucking firm.

Williams works as a warehouseman and plans to enroll next fall as a part-time student at Cal State Dominguez Hills to complete his degree.

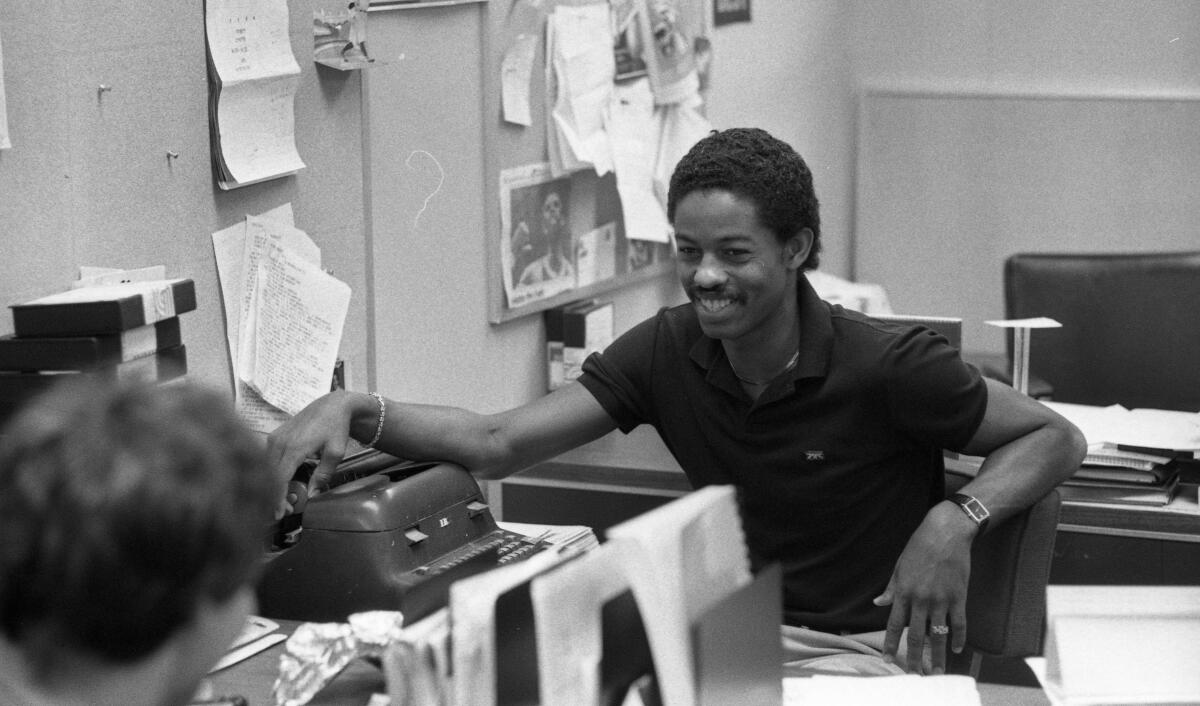

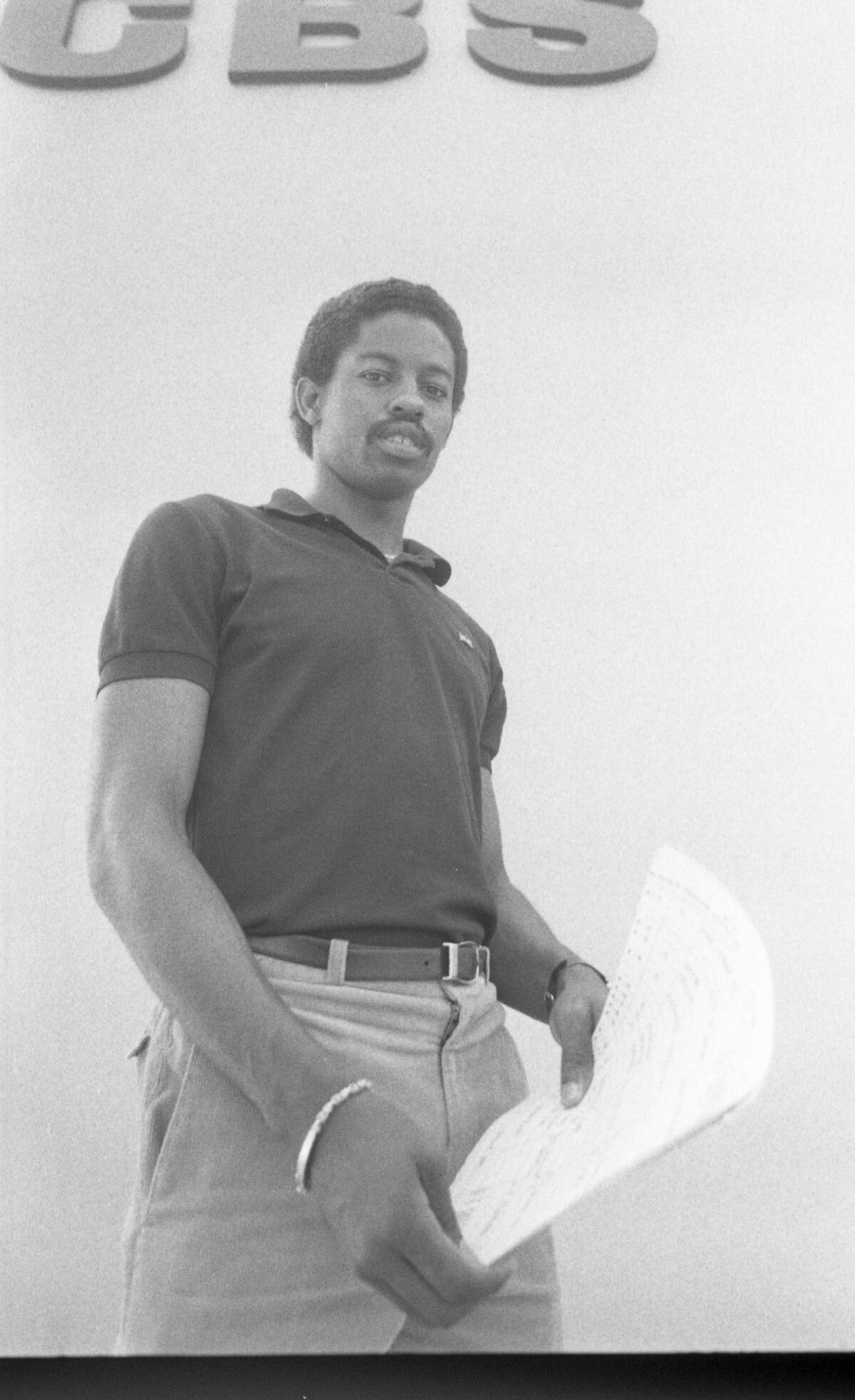

Hamilton, after comeback attempts with a minor league team and the NBA’s New Jersey Nets failed, went to work at a Los Angeles television station as an editorial assistant, where he still hopes to get another call from the pros.

After leaving Nevada Las Vegas in his senior year, Brown played professional ball in Europe and Mexico, hoping to attract the attention of the pros. Finally he got a chance.

In January, 1981, he signed a 10-day contract with the NBA’s Washington Bullets. He played a total of 90 seconds and was released. Now back in Los Angeles, he works an occasional job, while practicing almost daily in the hope that someone will need his skills.

“I’m not going to let this get me down,” he said.

But that pronouncement has a hollow ring. Brown is now 27, the age when the average NBA career has already ended.

Considering its collective goal, the team has fallen far short. In comparison to others, however, it has fared remarkably well. In Verbum Dei’s 20-year history, which includes five CIF players of the year since 1971, several all-Americans and all-CIF players, only one student from the hundreds who have played sports there over the years has ever made a career in the pros — David Greenwood.

Some Question Path

As the Verbum Dei players look back over their lives, some question the path they took.

“Like a lot of guys, I got caught up in sports,” Tackwood said. “I played ball almost 24 hours a day. At school I would play football for about three hours, basketball for another two hours. After school I’d play basketball for another three or four hours. It was like a job.

“If I had to do it all over again, I would still be going to school, working on my masters or something.”

Shaw realized that he stayed in the game too long.

“By the 11th grade, I should have realized that it was a no go for me,” Shaw said. “I should have spent more time on academics. There are millions of kids playing basketball across the country, and they’re not thinking that only 300 can play in the NBA. You don’t realize until it’s too late that the numbers are against you.”

Despite the failure of such outstanding players as Brown and Hamilton to make it in the pros, new dreamers who envision themselves slam dunking over Dr. J, skirting past linebackers or hitting the game-winning home run are not deterred.

“They think, ‘It’s not going to happen to me,’” said Verbum Dei’s principal, Father Thomas James. “It’s just human nature. Here I am smoking a cigarette although I know it kills people. It’s just that I think it’s not going to happen to me.”

Greenwood sees the concentration on sports by black youngsters as a failure of parents and teachers to provide guidance.

“These kids see sports figures on TV, and they are the only heroes they know about,” he said. “Blacks have made a lot of contributions these kids know nothing about.

“It’s up to teachers to teach black children, for instance, that Benjamin Banneker, a black man, helped to design Washington D.C. It’s up to parents to set standards for their kids instead of letting them watch TV all the time.”

::

Derrick Dorsey is a 6-3, 180-pound starting guard entering his senior year at Verbum Dei. He is considered one of the blue-chippers in next year’s college recruiting wars. He has already received letters of interest from USC, Iowa, Fresno State and Pepperdine.

His “lifetime dream”: a career in the pros.

“I’ve always wanted to play ball in the pros,” he said. “It would be a dream come true.”

And to that end he has applied himself. Spurred on by his mother, Dorsey began playing basketball the moment he entered junior high school, and by the time he had finished, he was one of those “special few.”

When it came time for him to choose a high school, his mother -- and the coach from his summer league team — sat down and decided on Verbum Dei because of its sound academic program. And its athletic program.

This summer, in between two jobs at two different liquor stores, Dorsey spent most of his time in five different summer basketball leagues. By the time he finishes, he will have played in 80 games — as many as the pros play all year.

Urged on by his mother, he has kept a solid 2.8 grade point average.

He had been told by David Greenwood, who occasionally visits the school, about the dismal prospects of having a professional basketball career.

“David has told us that there is a one in a million chance of making it to the pros. He said just to get drafted is a privilege.”

But Dorsey is not deterred, even though “a lot of my family have strived for it and not made it.”

“Nobody in our family has gotten as far as I have,” he said. “I’ve worked hard to make it to the pros.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.