From the Archives: ‘Midnight Cowboy’ rides Manhattan’s lower depths

- Share via

What ought to be said right away, because it’s easy to forget it after the fact, is how radically “Midnight Cowboy” differs from a certain set of expectations we might have had for it. The story of a good-looking blond buck from Texas fired with simple-minded dreams of making it as a stud hustler in Manhattan could easily have become another of the gamy sexual permutations which the screen is so earnestly examining for us these days.

But John Schlesinger‘s film, which begins an exclusive run at the Bruin Theater in Westwood on Wednesday, is instead an invariably moving study of unlikely (and unsexual) friendship and of collaboration for survival in the sad and gritty shadows cast by the bright lights of Times Square.

It evokes Manhattan’s lower (if not lowest) depths with a fidelity which recalls George Orwell’s “Down and Out in London and Paris,” a world of grifters, drifters, pawn shops and all-night coffee counters whiter and colder than icebergs.

It is a world whose Everyman needs a shave and soles for his shoes and is grateful if he can swipe a packet of crackers. It’s the place of kinky and furtive encounters, where unlikely dreams have long since eroded into 24-hour nightmares of failure and loneliness.

It sounds unbelievably grim, which does not prepare you for the raucous and ribald humor of “Midnight Cowboy,” or for its astonishing tenderness and sensitivity and its defiant hope, whose tragedy is at last not so much of place as of personality and the pursuit of bad dreams.

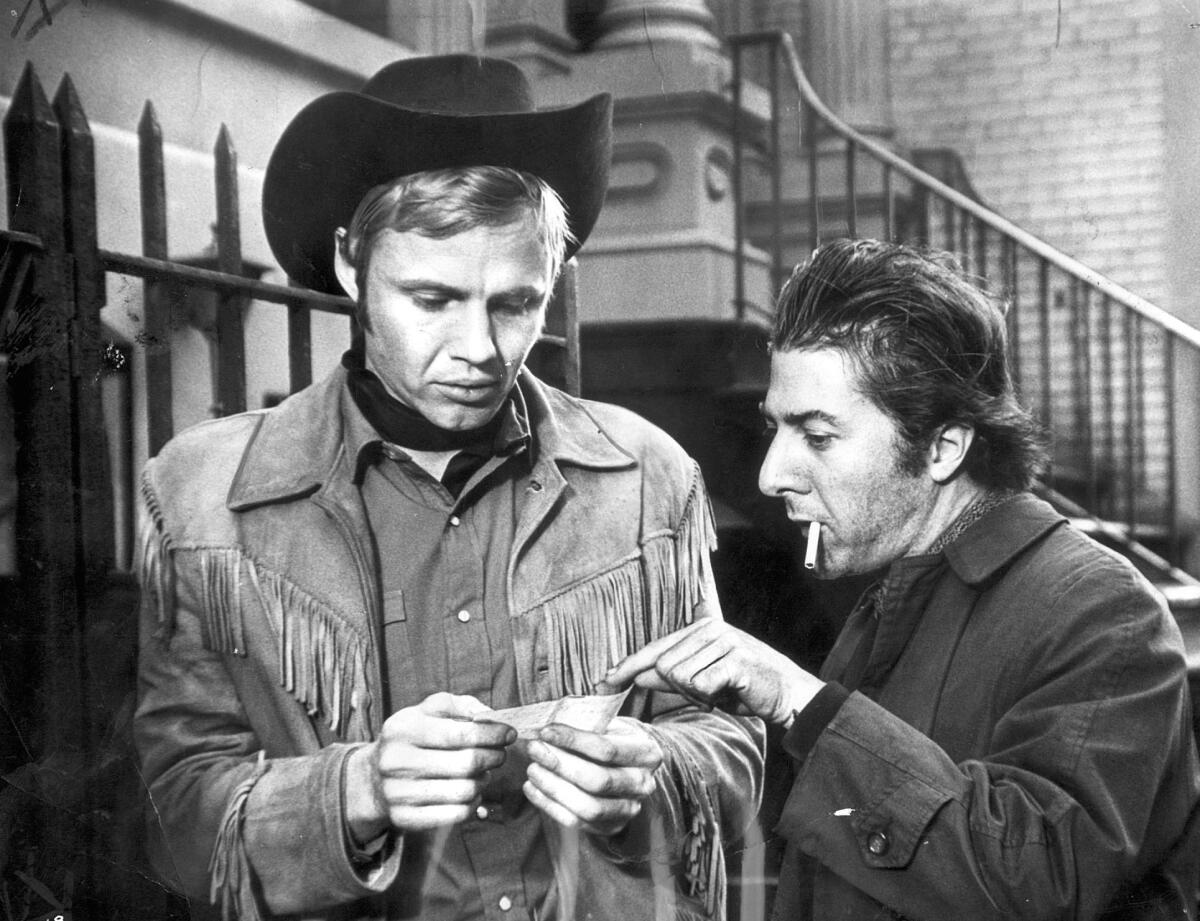

Dustin Hoffman as Ratso, a gimpy Bronx Italian who could hardly be further away from the world of “The Graduate,” creates a character so whole, so convincing, so singular, that it takes no little effort to remind ourselves that the same actor was also the collegian in pursuit of Katharine Ross and Mrs. Robinson.

Newcomer Jon Voight as Joe Buck, the refugee dishwasher from a Texas beanery, is so powerfully persuasive in his high-pitched drawl and cowboy costume that you read with disbelief he is a product of Yonkers, N.Y., and a Texan only for Schlesinger’s purposes. Voight is in fact a major addition to the family of important American actors and his portrayal of a good-hearted lunk, who life has kicked around pretty good and who tries to create one myth so as to pursue another, is damn near perfect. He is sensitive and insensitive, childlike and all too adult, comical and pathetic.

The success of their collaboration as actors has few parallels that I can recall in recent times. It seems clear that Voight and Hoffman discovered their characters together, and revealed them through speech which often has a just-found, improvisational quality. Their relationship as characters — the penny-ante street grifter and the stud hustler trying with desperation to find anybody who wants to be hustled at a price — moves with unwavering credibility from trickery to rage to tolerance, to concern, to loss.

(The postlude, so to speak, seems to me to suggest a grenade with a pin pulled. No small part of the skill of Schlesinger and Waldo Salt, who did the brilliant script, is that we are left at last to imagine the last playing out of a desperate biography.)

As an exercise in filmmaking, “Midnight Cowboy” is dazzling; indeed, once in a while it seems almost too dazzling for its own good. Schlesinger has, for instance, made extensive use of subliminal flashbacks, a device which is not exactly new hat at this time. Yet the logical way in which these flashbacks are triggered by events in present time struck me as the best use of the technique since perhaps “The Pawnbroker.”

Then, too, the flashbacks are fragmentary, almost inchoate (and frequently very difficult for the viewer to decipher until he can at last assemble the whole mosaic in his own mind). As such they seem to me to be a far truer simulation of an actual stream of consciousness (or subconsciousness) than the flashback usually provides. In story terms, they sketch the life path which led Joe to New York — sluttish mother, vanishing father, young and oversexed grandma with lots of visitors, a gang rape which cut both Joe and the girl he loved — and if the bio is arguably expendable, I’d argue that it is invaluably illuminating.

Other grandeurs of technique work not so well, or rather they work fairly well but in some violation of the naturalism of the rest of the movie. These include a funny set piece with a kaleidoscopic television set while Joe romps in bed with a lady he thinks he has hustled, and the fantasy sequence for Ratso, which quickly comes to seem a writer’s invention, not his.

“Midnight Cowboy” is overwhelmingly a two-character story in which nobody else matters much, yet the excellence of its subsidiary casting is another of the satisfactions of the picture. Among the most impressive of the supporting roles are Jonathan Kramer as a guilt-haunted middle-aged homosexual, John McGiver as a religious screwball, Sylvia Miles as a faded blond lady in bed and Brenda Vaccaro (excellent as a secretary in “Where It’s At”) here wryly and prettily amusing as the one legit customer Joe Buck finds. Ruth White is splendid as Joe’s grandmother and Jennifer Salt does extremely well in the highly emotional role as his girl. Bob Balaban is excellent as a young homosexual.

As Schlesinger proved abundantly in “Darling,” he is a careful and perceptive witness to the world we live in. In “Midnight Cowboy,” the suspicion is that he has as an Englishman seen these special sectors of the American milieu with a visitor’s freshness and clarity of sight and insight: the real as against the mythic Texas, the real as against the (tall) storied Manhattan. On a limited scale he has also found and showed us the folk faces which lent such a seamed fascination to his “Far From the Madding Crowd.”

There is, I must say, a long psychedelic party in the Village, an event I hope we can hereafter regard as sufficiently documented by the movies. But I must also say that Viva, Ultraviolet and International Velvet help make Schlesinger’s party as successful as any such party is ever likely to be.

John Barry is credited as musical supervisor, which I take to mean that in addition to his own country fusions he oversaw the pastiche of pop sounds which place “Midnight Cowboy” so accurately, if jarringly, in our time. Toots Thielemans plays lonely harmonica, singularly right for a picture with so much to say and show about loneliness.

The excellent photography is by Adam Holender, and in the story in which sound has a special importance (Joe Buck’s security blanket is a portable radio), special mention is due to the team of Jack Fitzstephens, Vincent Connelly and Dick Vorisek.

Jerome Hellman produced, and has overseen a strong and important film. “Midnight Cowboy” discovers an unattractive slice of our lives and it is unquestionably not a family film. Yet beyond the specifics of circumstance (or out of the press of circumstances) it also discovers compassion, self-sacrifice and a kind of stubbled nobility among men who themselves discover it only in time to realize what might have been.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.