From the Archives: Magnificent ‘Ben-Hur’ inspiring in premiere

- Share via

Last night “Ben-Hur” had its formal West Coast premiere at the Egyptian Theater. Although leaders from all ranks of social Los Angeles and Hollywood attended the usual forecourt festivities were largely dispensed with. This was in keeping with the spirit of “Ben-Hur,” which has been subtitled “A Tale of the Christ.” Opening-night proceeds, with tickets selling at $25, $50 and $100 were donated to the worthy Scholarship Fund of the University of Southern California Medical School. The Egyptian’s capacity is 1,392 souls.

Latest, finest

I find it hard to believe that any of the 1,392 lived through the experience unmoved in greater or less degree.

For its $15 million remake of Gen. Lew Wallace’s bestselling novel MGM called on some of the most seasoned minds in Hollywood, and to their combined know-how added the latest and finest in technical and electronic development — a wide-screen process, Camera 65, color and stereo sound.

True, most of it was shot in Rome. with Italians participating, and the cast is “international.” Nevertheless, “Ben-Hur” carries the hallmark and all the qualities for better or worse, but immensely more for better — that once made Hollywood the filmic center of the world.

All the adjectives

MGM has delivered the “Ben-Hur” it promised. It is, whatever the minor pros and cons that will rage over it, magnificent, inspiring, awesome, enthralling and all the other adjectives you have been reading about it.

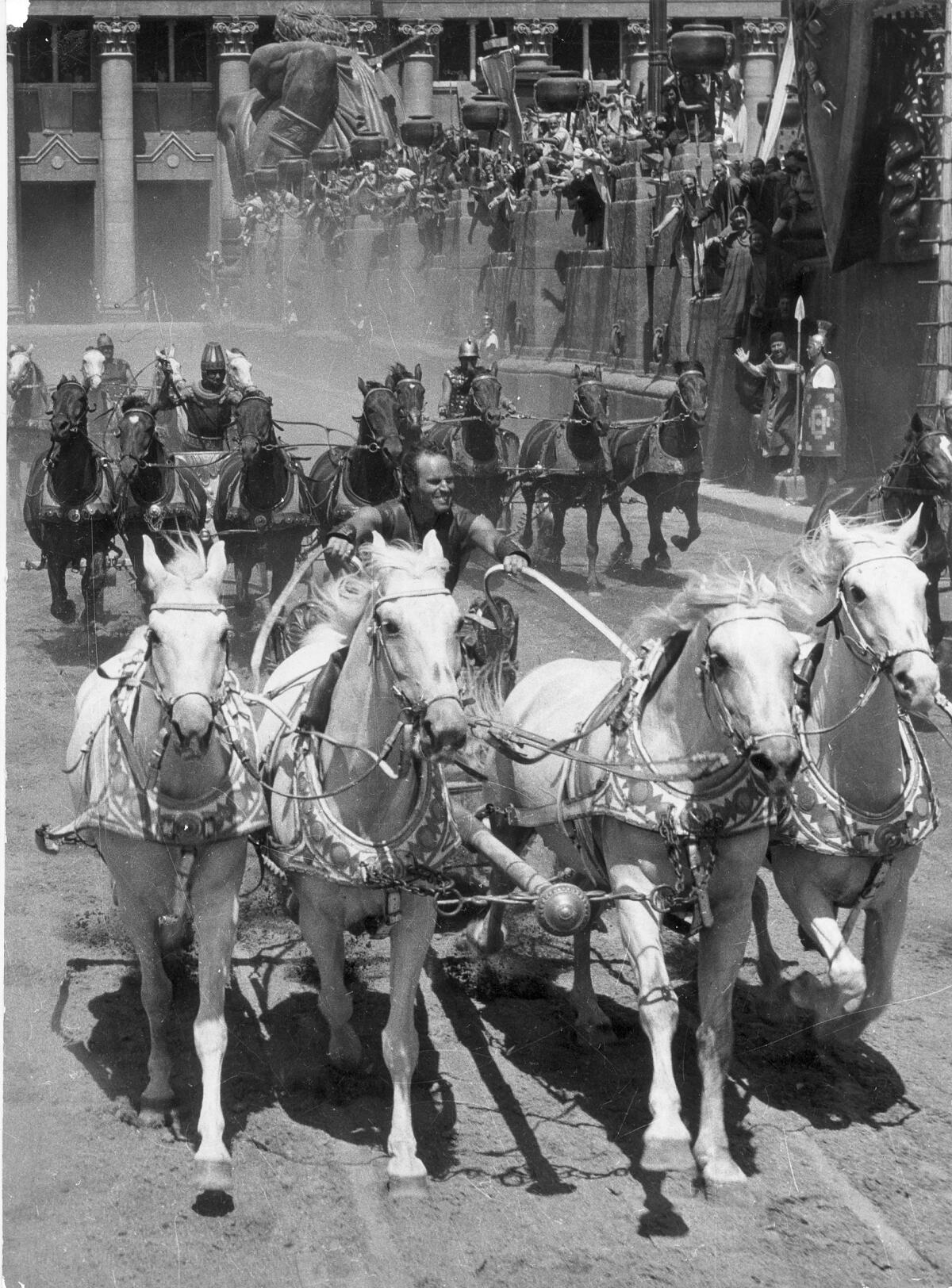

Its race marks an all-time peak in action attained by any camera anywhere — 10 minutes of hurtling chariots, flying horses and berserk supermen. I doubt if old Jerusalem ever saw anything like this, but what would “Ben-Hur” be without it? As a work of art its most serious fault is overstatement.

The picture has its excesses — a charge frequently leveled at the late C. B. De Mille and they are apparent in spite of the reining hand of “conservative” director William Wyler.

Inner conflict

This is simply the old inner conflict between the dedicated moviemaker, amazed by what he has wrought, and the artist of taste — when to break off with a point already made and when to let it run on for a post-climactic effect. In its over-all four hours, “Ben-Hur” is the third longest movie by a matter of minutes.

Some of its sequences probably are too long, not only in the dialogic sense (though this is to plant story points) but also in such visual sequences as the rowing of the galley slaves, built up musically a la Ravel’s “Bolero,” and the climb to Calvary.

Here again, though, the cumulative effects are admittedly tremendous. And so ...

I suppose this last sequence will arouse the most partisan discussion, for no version of Christ’s Passion will ever be definitive. Wyler has filmed it realistically, with much emphasis on brutality and blood, as, indeed, he has many other scenes.

My own feeling is that there was too much of the lepers, Ben-Hur’s mother and sister, not only in the repeated revelation of their disfigurement but also in the retarding tempo of their wraithlike flittings. But these, of course, are to prepare us for the later miracle and for contrast.

The editing is generally expert, considering the episodic nature of the story. Some of the cutting back and forth is jarring and the breaks between a couple of sequences are abrupt.

Common cause

The plot, I imagine, needs no retelling.

The Jew, the Arab and the Christian here find more or less common cause against Imperial Rome, and the film is careful of the sensibilities (since the Caesars are past offending) of the first three.

It is an epic saga of Judah Ben-Hur, the Jewish prince banished to Roman serfdom who after many vicissitudes returns to his people and is converted to Christianity.

Wyler, whose extremes are as often matched by subtleties, has more nearly bridged the centuries between Christ’s and ours than any other moviemaker. “You are there.”

I have not meant to slight the cast in all this. It is they who give it life.

Charlton Heston is required to run an almost impossible gamut and just about does, though he is more compelling in the physical than the spiritual aspect.

Strong conviction

Stephen Boyd plays his arch-enemy, Messala, with strong conviction and makes a formidable antagonist, even if his friendly Irish face sometimes belies him.

Hugh Griffith gives the whole film a needed lift as the jolly, rascally Sheik Ilderim, and Jack Hawkins leavens his imperious Quintus Arrius with a saving humor, too.

Among other well-chosen character men are Finlay Currie (Balthasar), Sam Jaffe (Simonides), George Relph (Tiberius), Frank Thring (Pontius Pilate) and Terence Longden (Drusus).

The Esther is Haya Harareet, whose Israeli origin and sincerity justify her casting in the part, and the sorely-smitten lepers are portrayed by Martha Scott and Cathy O’Donnell.

Honor due Zimbalist

All honor is due Sam Zimbalist, the producer, himself fatally stricken while in Rome.

The screenplay is credited to Karl Tunberg, with side-long acknowledgement by the studio also to Christopher Fry, S. N. Behrman, Maxwell Anderson and Gore Vidal.

Robert Surtees was director of photography and the skillful score is by Miklos Rozsa.

Second-unit directors (the chariot race) were Andrew Marlon and Yakima Canutt.

Along with Wyler, I salute them.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.