From the Archives: ‘Best Years of Lives’ saga of homecoming

- Share via

“And the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough ways shall be made smooth ...”

So should it be for the returned soldier. Such is the obligation of a country and a people, relieved of the crucial danger of war.

This, in essence, it would seem, is the message of “The Best Years of Our Lives,” Samuel Goldwyn production, narrating the experiences of the serviceman who has come back to his home.

It is the finest subject of its type yet made visible. It has the genuine note.

Road-show booking

The film opened as a challenging reminder of the great World War II, that is, perhaps, being all too easily forgotten, yesterday afternoon at the Fox Beverly Theater. It is being screened in the road-show manner, with two performances daily, except for some special added holiday presentations.

Dated? Yes, some people will doubtless call “The Best Years of Our Lives” that — simply because it deals with the soldier’s reentry into civilian life. That sort of picture is now often described as one that Hollywood has put on the passe schedule.

But actually a sound, solid, real impression of life in a cinema can never be untimely, and William Wyler, as director, whose war experiences were extensive; writers MacKinlay Kantor and Robert E. Sherwood, and the superlatively chosen cast attain just such an impression in this unusually human and appealing, and frequently very diverting, feature.

Paratrooper shines

What most differentiates “The Best Years of Our Lives” from other postwar emprises is the presence of Harold Russell, the ex-Army paratrooper. He appears as one of the three central male figures whose stories are related.

While his is not an acting part of great exactions, he succeeds in bringing enormous impact through the utter simplicity and sincerity of what he does. His work endows “The Best Years of Our Lives” with factual power.

The Russell adjustment to the civilian environment is a deeply wrought thing — the most moving and central development in the plot. What the war brought him, besides ephemeral glory, is a physical tragedy that has beset many men — loss of hand or foot or other permanent disability.

Russell symbolizes these men and their courage, even as the young girl (Cathy O’Donnell) typifies the faith and loyalty of the women who remain devoted.

March brilliant

One could write reams about Fredric March and the brilliant gayety of his performance. He really “celebrates” his homecoming, with Myrna Loy and Teresa Wright trying to help him keep at least one foot on the ground! His scenes are sensationally funny.

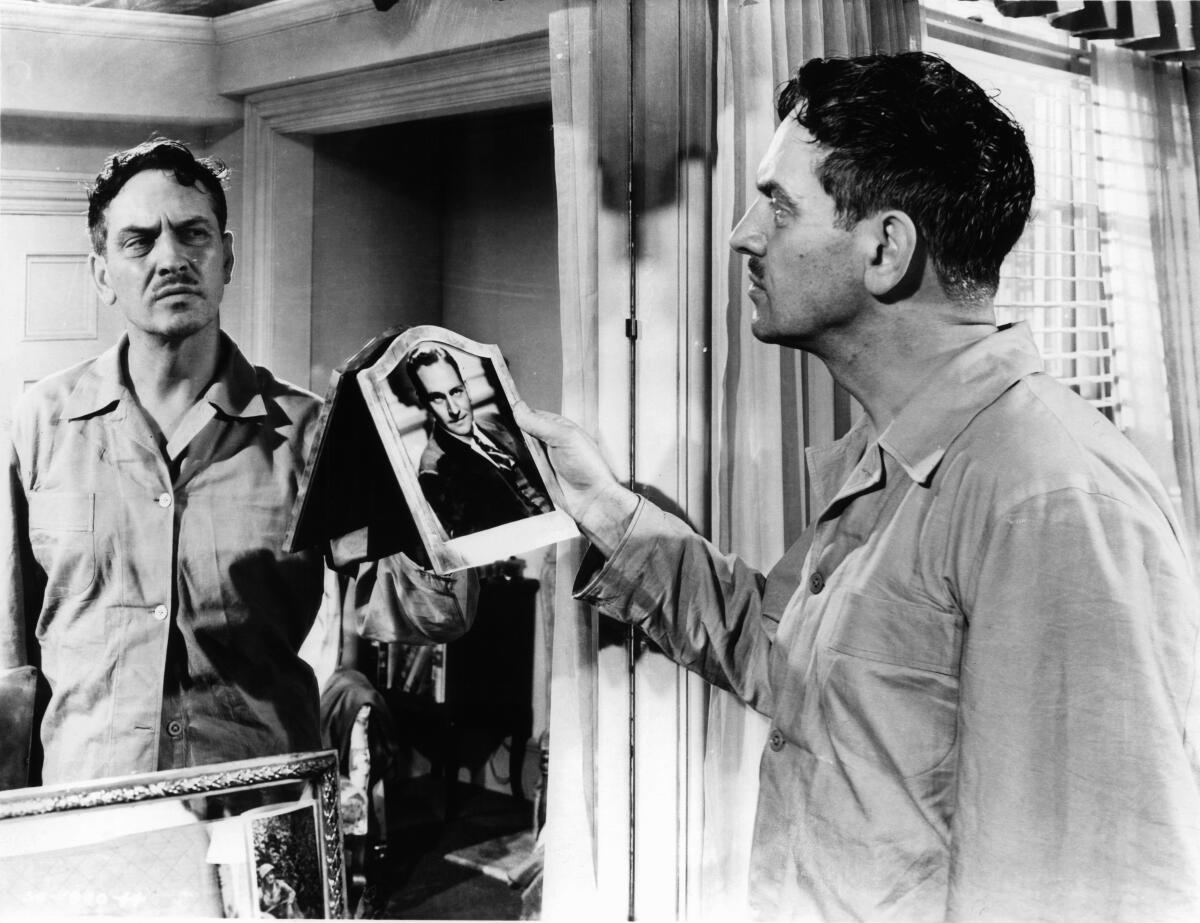

Dana Andrews and Virginia Mayo provide another “typical” instance — the man that was big in the service, who can’t rise to that estate in civilian life — at least in the estimation of a shallow and mercenary little flibbertigibbet of a wife. Andrews and Miss Mayo give superexcellent delineations.

In fact, the acting is notable throughout, and certainly “The Best Years of Our Lives” will Academy-contend in a big way.

Hoagy Carmichael is to be well noted, as nearly always, and Gladys George and Roman Bohnen, though briefly observed, contribute. Minna Gombell, Steve Cochran, Ray Collins, Walter Baldwin and numerous others appear.

The debut of Miss O’Donnell is to be most favorably recognized.