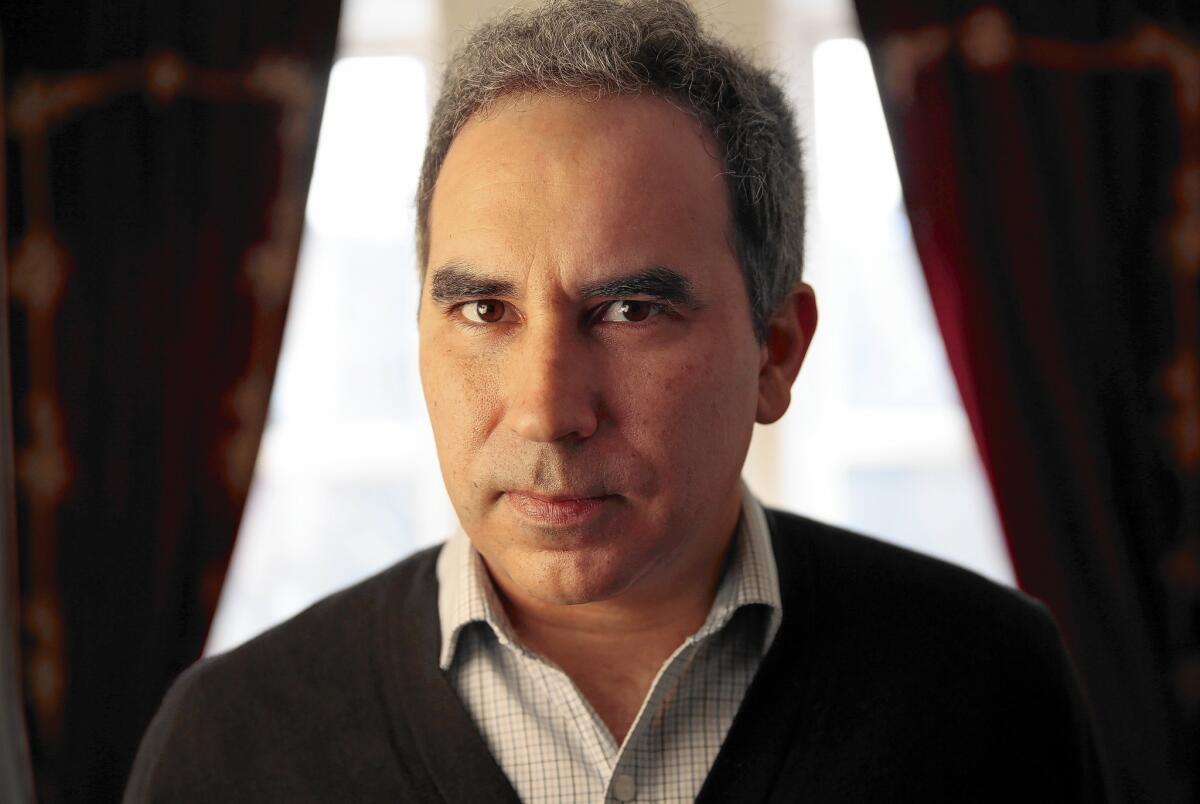

David Grand conjures early L.A. in ‘Mount Terminus’

- Share via

“I developed a phobia of Los Angeles,” says David Grand.

That could have been a problem for the 45-year-old author, whose novel “Mount Terminus” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 384 pp., $26) is set in early 20th century L.A. But it was the book — which he spent more than a decade writing — that estranged Grand from the city where he grew up.

“I couldn’t deal with the sensory overload I experience when I’m there,” he says from the safety of his Brooklyn walk-up. “Whether it’s the light or the landscape or transitioning from one dynamic neighborhood to another, I just kept thinking I’m going to see all these people trampling the sacred ground that I’ve been constructing for all of these years.”

What Grand has constructed is a layered literary take on creativity and silence, identity and ambition, storytelling and filmmaking and solitude. In it, Bloom, a young boy, is brought by his father to Mount Terminus, which looms over the not-yet-built city of Los Angeles. For his father, Jacob, California is a place of both refuge and reckoning; he is, like many who came here, running from something and trying to start anew.

Before his history catches up to him, Jacob creates a home for his son that’s idyllic and free of want but also isolated. Bloom is raised in their hilltop villa with no companions but a deaf and mute maid. He is a product of this world, perfectly suited to its solitude and quiet.

“I chose the interior space of Bloom,” Grand says. “I wanted to create the feeling that he was this odd, lonely guy with a rich imagination who was very comfortable in a world of silence.”

“Mount Terminus” is dense and intense. Thank Grand’s process: Write several pages one day, compress them into a few lines the next. Then do that again and again for 10 years.

That’s a long time for an author to stay out of circulation. And those who remember Grand for his well-reviewed earlier books — 1998’s “Louse,” a satire featuring a Howard Hughes-like mad billionaire, and 2002’s “The Disappearing Body,” a 1930s noir — won’t find many similarities here. Except, of course, for a determination to create something entirely new.

He’s been busy while writing: He’s married, has twin sons, and teaches creative writing at Fairleigh Dickinson University. One time-sapping activity he has managed to avoid is social media. “If I had my choice I would like to lead my very simple life, not put myself out on public display when I have an interesting, idiosyncratic idea.... I kind of reserve that for my work — which is why I could sit around for 10 years and work on a book,” he says, laughing.

During the course of our video interview, he cracks up when he says something weighty or serious. It’s a little self-deprecating, maybe, but it’s also delightful: not what you might expect from someone who has spent a decade creating a serious work of art.

In “Mount Terminus,” Bloom becomes a young storyboard artist, a man who envisions how stories can come to life frame by frame. Of course, he never would have emerged from the mountain if not forced to; that impetus arrives in the form of his elder brother Simon, an ambitious film producer and real estate developer, poised to bring the whole city into being all by himself. The mogul-on-the-make is a familiar story, Grand knows, so he puts it on the periphery while history unfolds at an even further remove.

What we have instead is a bildungsroman of Bloom, a portrait of the artist growing into his creative self, and secondarily becoming a man. Will he, can he, should he learn to live in the world?

It creates a new literary hybrid: the Los Angeles Gothic. “Once you put a big house on a hill, you’re entering the Gothic; there’s no way of getting around it,” accedes Grand. Like the latter-day noir of the film “L.A. Confidential,” there’s a thrilling contrast between the bright light of Southern California with the dark emotions and actions of the humans who move through it.

“I had that feeling when I was growing up: My moods were a little too dark for sunny Southern California,” Grand says. His parents divorced acrimoniously in New York when he was 8, and his mother, a teacher, moved David and his brother to an inexpensive apartment in Westwood.

Grand was raised “a good Jewish boy,” attending Sinai Temple on Wilshire Boulevard. Some of his Jewish heritage makes it into the book, but it’s the lost history that’s more important. Bloom’s family tree pretty much stops at Ellis Island, something he shares with Grand.

“I know very little about my family history — it’s kind of a blank slate. I got a few stories out of my grandmother before she passed away. Nothing earth-shattering or groundbreaking: just people getting thrown under trains and houses being burnt down. All of the horrors one would expect from, you know, a pogrom,” Grand says. “That’s part of the Jewish experience that I wanted to relate in the novel, the absence of family history.”

But that lack inspired self-invention. “It doesn’t surprise me that a bunch of Jews wandering the desert would find themselves in a place like Los Angeles building a dream factory,” Grand says.

The texture of early Hollywood comes to life in the book as Bloom apprentices under a director making silent-era audience-pleasers, then works for a visionary filmmaker.

“I wanted to create the experience of a silent film in that character; I wanted him to embody it,” Grand explains. That melding of form and content is impeccable throughout “Mount Terminus.” Bloom’s mother’s life takes some operatically dramatic turns — which Grand describes as being “the type of experience that age would have had. I didn’t want to shy away from that overinflated emotion and the melodrama.”

Grand learned that lesson from a Russian poet he studied with in college. “He must have been 90,” he says. “He was always wagging his finger at us, saying, ‘Oh, you people. I grew up in a poetic age. I grew up in an age where people were unafraid to feel. I look at you, I feel so sorry for you.’”

It doesn’t matter to Grand that melodrama isn’t often found in contemporary literary fiction. “I just decided I’m just going to embrace it. I’m going to go for it. Because that informs so much of the cinema that emerged in that period. That raw emotion.”

Now that Grand has completed the world he envisioned for Los Angeles in the earliest days of cinema, he’s ready to return. “The second I finished, my first thought was, ‘I can’t wait to go back to L.A.’ I miss it,” he says. He reads at the Last Bookstore on Thursday, after making a run to In-N-Out.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.