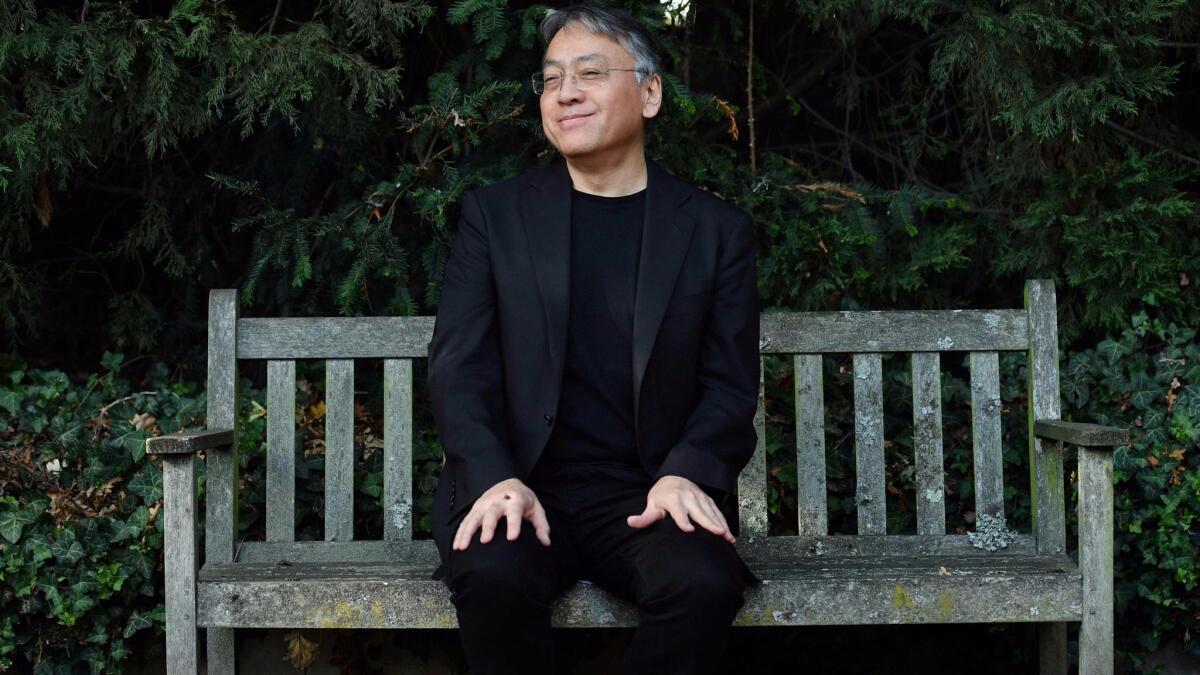

British writer Kazuo Ishiguro is a rarity and now a Nobel laureate

- Share via

Among literature fans, Thursday’s Nobel Prize announcement came as a surprise. The author of “The Remains of the Day” and “Never Let Me Go,” though a critically acclaimed and respected novelist, had been on no one’s shortlist.

But then Kazuo Ishiguro, the 2017 Nobel Laureate in Literature, has always been surprising.

He is, after all, that rarest of creatures — a literary craftsman who also sells books. Ever since the 1989 publication of “The Remains of the Day,” winner of England’s prestigious Booker Prize and adapted into an Oscar-nominated film starring Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson — Ishiguro has regularly landed on U.S. bestseller lists.

That’s not always true of Nobel laureates, popularity with American readers not being one of the Swedish Academy’s criteria.

“Kazuo Ishiguro is a terrific choice for the Nobel Prize. He is both a popular and accessible writer, and yet also one who is smart, sophisticated, inventive, and experimental,” said Viet Thanh Nguyen, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and a professor at USC.

Ishiguro had no advance warning of the award and was at home in London answering email when he got the news, which at first he thought was a hoax. “It’s a ridiculously prestigious honor,” he said in a phone interview with the Swedish Academy that was uploaded to YouTube. “I come in the line of lots of my greatest heroes. Absolutely great authors. The greatest authors in history have received this prize.”

The author of seven novels, a short-story collection and screenplays, Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki, Japan, in 1954; his mother had survived the atomic bomb attack as a teenager. He moved at age 5 with his parents to England, where his father worked as an oceanographer. His parents intended to return to Japan but never did. Still, the idea of the birthplace he didn’t know left such a lasting impression that it was a setting for Ishiguro’s first two books, “A Pale View of the Hills,” published in England in 1982, and “An Artist of the Floating World,” published in 1986.

But it was when he turned to England that Ishiguro’s work found its driving force: the tension between what is unexpressed and the thread of memory. “The Remains of the Day” looks back on the period between the world wars and, through Stevens, a loyal butler, observes British leaders that the reader can see are making dangerous choices even if Stevens cannot until it is too late. “The author’s subtlety and coolness are fascinating,” wrote Patricia Highsmith in the L.A. Times review. “‘The Remains of the Day’ is a book to make the reader feel happy and at ease on being introduced to the world of the civilized Stevens and his social superiors. The humor is sly, unwitting, and charged with social comment.”

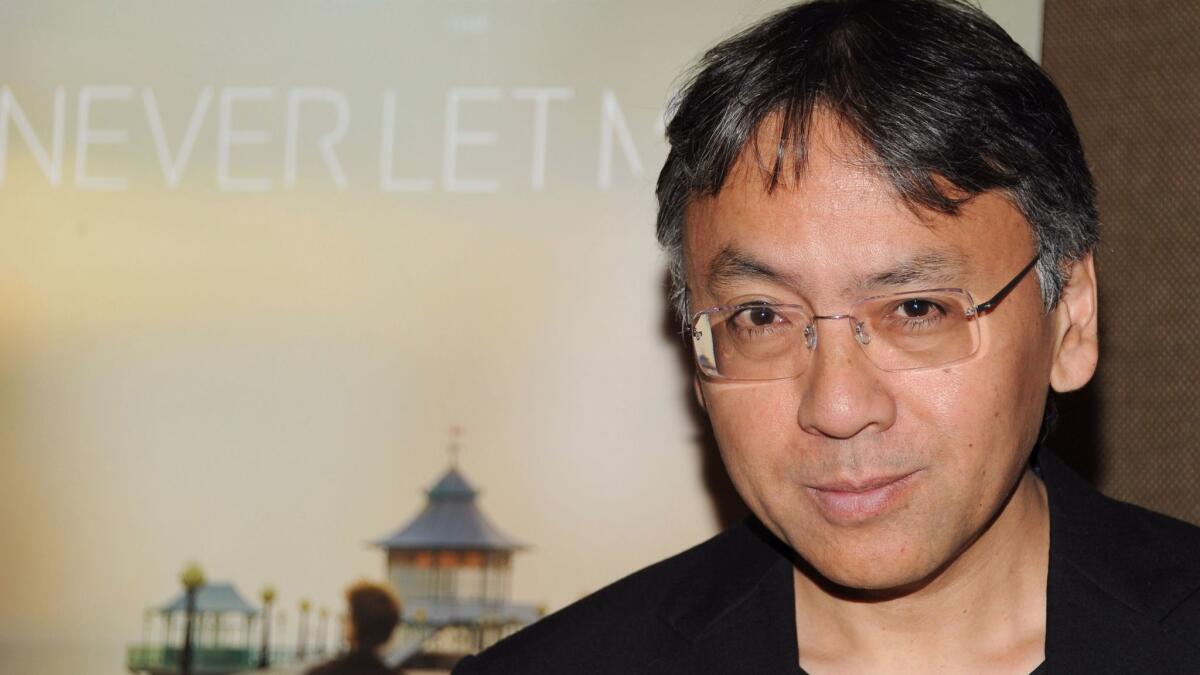

Emotional restraint, moral complexity, self-delusion and the fragility of memory run through Ishiguro’s works, which have quietly pushed the boundaries of literary fiction. His most recent novel, “The Buried Giant,” is set in Arthurian England and its inclusion of ogres sent at least one prominent critic to dismiss it as “ungainly” and worse. “I didn’t anticipate this bigger debate,” Ishiguro told Neil Gaiman in a 2015 interview with the New Statesman. “What is genre in the first place? Who invented it? Why am I perceived to have crossed a kind of boundary?” He’d already dabbled in science fiction — “Never Let Me Go,” set in a seemingly idyllic British boarding school, was a well-received dystopia (and was also turned into a movie).

Ishiguro attended British boarding schools and before college took time off, in 1974, to hitchhike around the U.S. with his guitar. He desperately wanted to be a musician, but when he felt that was not going to happen, he turned his talents to fiction.

He studied philosophy and literature at the University of Kent, where he sang and played in a band, and got a master’s degree in creative writing at the University of East Anglia. Steeped in the idealistic social movements of the 1960s and ’70s, he worked for several years helping the homeless and on housing rights; his wife, Lorna, is a social worker. Yet he also worked flushing grouse for hunters at the British royal family’s castle Balmoral, in Scotland.

An underlying tension informs Ishiguro’s works, Nguyen points out. “The fact that he is a writer who embodies some of the issues around migration, displacement, and otherness — by virtue of being a Japanese-born but British-bred author writing in the most beautiful English — is also personally resonant with me. He came to England at five; I came to the United States at four. I can understand why he was able to write a novel like ‘The Remains of the Day,’ about an aging British butler in a dying system of class and empire. Ishiguro could see from within that system and yet look at it from the outside as well.”

In 1990, Ishiguro sat down with The Times to talk about “The Remains of the Day.” “In British and Japanese society, the ability to control emotions is considered dignified and elegant,” Ishiguro told The Times. In Stevens, there is “the tendency to mistake having any emotions at all with weakness.”

“Ultimately,” Ishiguro said, “the book is about the tragedy of a man who takes that thing too far, who somehow denies himself the right to love and be human. This is something the middle-class and upper-middle-class English do a lot.”

In its citation, the Nobel committee praised Ishiguro “who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.”

Sara Danius of the Swedish Academy said, “If you mix Jane Austen and Franz Kafka you have Ishiguro in a nutshell — and you have to add a bit of Proust into the mix.”

The literary references were clear. Last year, the academy awarded the Nobel in literature to American musician Bob Dylan, citing his work as poetry. The decision made headlines, not all of them good. Danius declined to comment, in a streaming interview, on how the selection of Ishiguro might be received.

For his part, Ishiguro didn’t think last year’s prize was a problem at all. “It’s great to come one year after Bob Dylan, who was my hero since the age of 13. He’s probably my biggest hero,” he told the Swedish Academy. “I do a very good Bob Dylan impersonation, but I won’t do it for you right now.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.