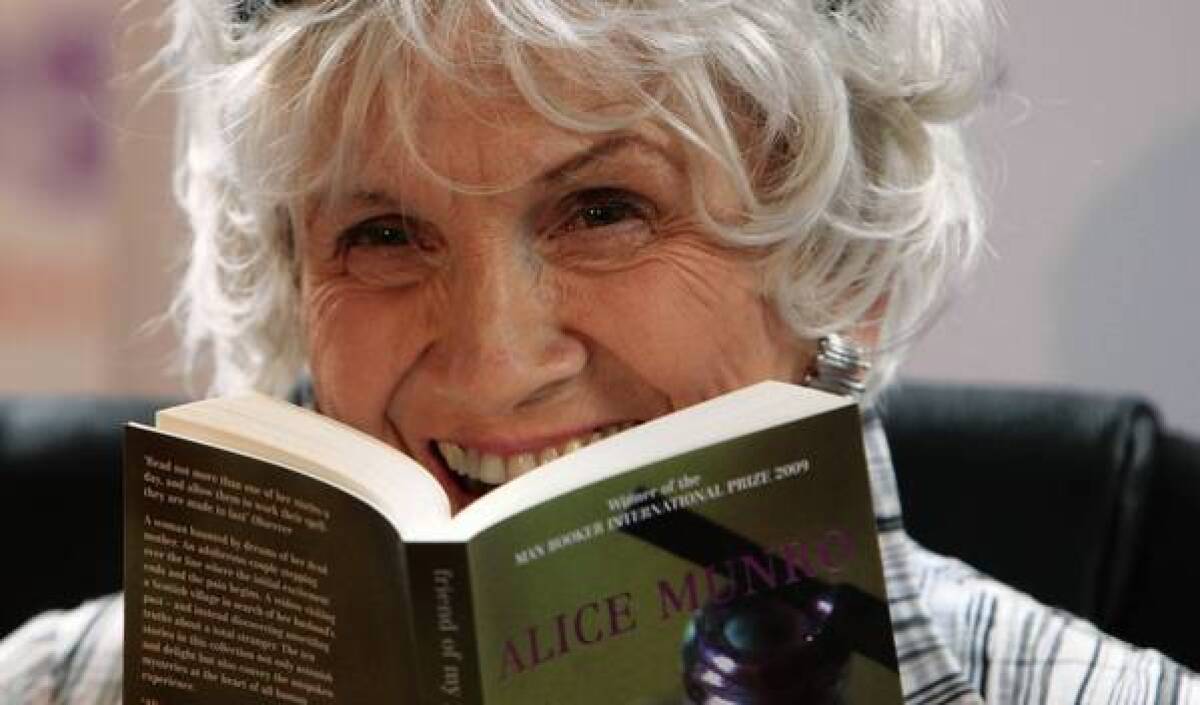

Alice Munro’s quiet, precise works lead to Nobel Prize in literature

- Share via

Alice Munro was nowhere to be found on Thursday morning when the Swedish Academy awarded her the Nobel Prize in literature. The permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, Peter Englund, had to leave her a voice mail. The short story writer surfaced briefly for a quick interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corp., and then dropped out of sight.

This is utterly in character, for Munro has never sought the spotlight during her remarkable career. The author of 14 books of fiction, she’s well-known to readers around the globe and a perennial Nobel contender for the acuity of her vision, the precision of her voice. Now 82, Munro publishes regularly in the New Yorker, and several of her stories have been translated into film, including “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” which was adapted by Sarah Polley into the 2006 film “Away From Her.”

In 2009, Munro won the Man Booker International Prize for her body of work, and this year, shortly after the publication of her most recent story collection “Dear Life,” she announced she would not be writing anymore.

She is in a class by herself: the 13th woman, first Canadian and first writer of predominantly short fiction to win the Nobel Prize. And yet, her work is less overtly political than recent laureates such as Harold Pinter, Doris Lessing and Mo Yan. Her writing is quiet, character-driven, using precise language to evoke the lives of everyday people, and the glories and heartaches to be found in ordinary lives.

“Many people write about marriage or childhood,” says Ann Close, her editor at Alfred A. Knopf since 1978, “but somehow she manages to get at things you’ve forgotten, and you think, ‘That’s how it is.’ I think hers is the most amazing work about women in this era that there is.”

Munro has lived for many years in rural Ontario, 20 miles from where she was born and raised. During her first marriage, in the 1950s and 1960s, she lived in Vancouver and later Victoria, where she and her husband owned a bookstore, Munro’s Books; she remarried in 1976 to geographer Gerald Fremlin, who died this year.

Through it all, she has written stories of extraordinary sensitivity and subtlety — “innovative, quiet, understated,” enthuses novelist Mona Simpson, who interviewed her for the Paris Review in 1994.

Her work also exhibits a sneaky fierceness, the ability to face the world on its terms.

“If you go to her first book,” says Munro’s longtime friend and colleague Margaret Atwood, “you’ll find all the key signature elements of her writing: the detailed but often hilarious descriptions, and the event that is transformative but doesn’t really change things in the end.”

In collections such as “Who Do You Think You Are?,” “The Progress of Love” and “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage,” relationships are often fraught and characters must deal with time not as a consolation but rather as an inevitable force.

In “Axis,” selected for “The Best American Short Stories 2012,” she describes the relationship of two college girls, Avie and Grace, which collapses when Grace gets pregnant and drops out of school. Years later, Avie — now widowed — meets Grace’s former paramour and recalls that there was also a spark between them, “water under the bridge,” but still inflected with a potent sense of loss.

“The miracle of an Alice Munro story,” notes novelist and story writer Marisa Silver, “is its deceptive ease.... But then, the layers of her tale peel back, she deftly dips and weaves through time, until you realize that the simple story of a woman searching for love, say, is actually the story of a time, a place, a set of sexual and social mores that by their very limitations force a character into confrontation with her deepest yearnings and regrets.”

In many ways, such a sensibility has its roots in Ontario, which has become, to steal a phrase from Faulkner, her “own little postage stamp of native soil.” But equally important is her experience as a young wife and mother. Much of her work is set there, among women (and some men) trying to carve out space for themselves amid family and responsibility.

This was Munro’s own experience, as a young wife and mother in the 1950s and 1960s, raising three daughters and trying to write.

“I used to work until maybe one o’clock in the morning and then get up at six,” she told the Paris Review. “And I remember thinking, You know, maybe I’ll die, this is terrible, I’ll have a heart attack. I was only about thirty-nine or so, but I was thinking this; then I thought, Well even if I do, I’ve got that many pages written now. They can see how it’s going to come out. It was a kind of desperate, desperate race.”

Desperation is a factor in much of Munro’s writing: the desperation to be seen, to be heard. In “The Ottawa Valley,” the narrator describes her Aunt Dodie: “The tragedy in her life was that she was jilted. ‘Did you know,’ she said, ‘that I was jilted?’ My mother had said that we were never to mention it, and there was Aunt Dodie in her own kitchen … saying ‘jilted’ proudly, as somebody would say, ‘Did you know I had polio?’ ”

There is, of course, a vivid power in such honesty: the power of owning up to who you are. Munro, however, had to struggle to achieve that, spending more than a decade writing the stories that became her first book, “Dance of the Happy Shades,” which won Canada’s most prestigious literary prize, the Governor General’s Award, in 1968.

Although her second book, “Lives of Girls and Women,” is called her only novel, it’s more a collection of linked stories, a strategy to which she has occasionally returned.

“She wanted to write novels,” Simpson says, “but stories fit better into her life. So she used her limitations; she molded circumstance to her own ends.”

In the introduction to her “Selected Stories,” Munro is more explicit. “I did not ‘choose’ to write short stories,” she writes. “I hoped to write novels. When you are responsible for running a house and taking care of small children, particularly in the days before disposable diapers or ubiquitous automatic washing machines, it’s hard to arrange for large chunks of time.”

That’s a telling statement, both in what it says about the challenges women continue to face in balancing work and family, and the remarkable, even revolutionary, intent of Munro’s work. Who needs novels, after all, when she has written stories that are as full as novels, in which time turns and telescopes and entire lives are revealed?

“Her stories only deepen upon further reading,” observes Elissa Schappell, author of “Blueprints for Building Better Girls,” in an email. “Reading ‘The Bear Came Over the Mountain’ as a young woman, I felt the wife was being bullied into entering a nursing home by her husband and I didn’t understand it. Now as a married woman in her 40s, it’s a love story, a terrible tragedy for both of them.”

As for Munro, she told CBC radio this morning, “I would really hope this would make people see the short story as an important art, not just something you played around with until you got a novel.”

The same is true of domestic life, the private lives of men and women (but, again, mostly women), which can and should be the substance of the highest literature — perhaps the most transformative idea of all.

Times staff writer Hector Tobar contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.