Reading Ferguson: books on race, police, protest and U.S. history

- Share via

Nearly a half century before Michael Brown and Officer Darren Wilson crossed paths on a street in Ferguson, Mo., a 21-year-old man named Marquette Frye was pulled over by the California Highway Patrol, just outside of Watts.

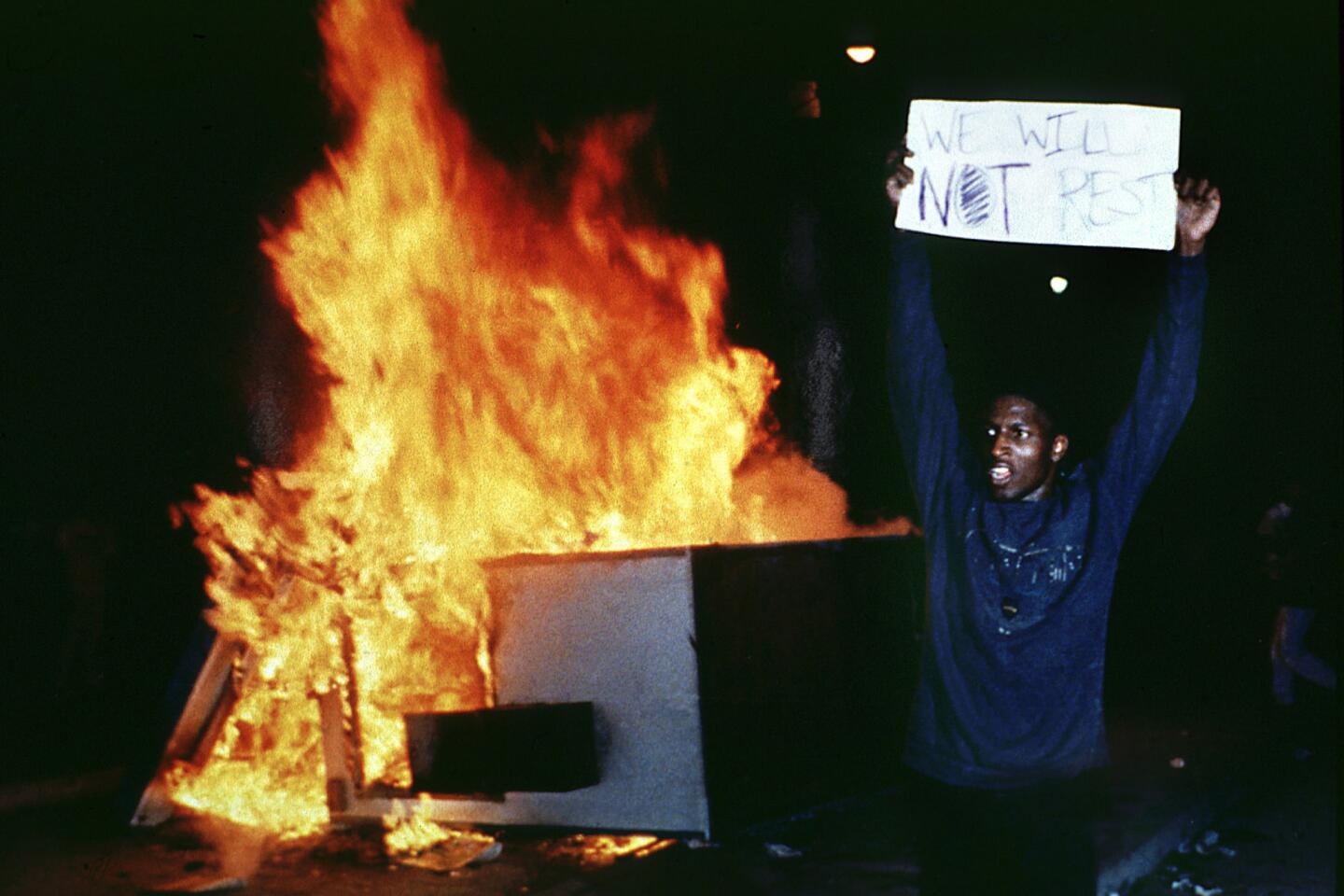

Both incidents unfolded on an August day, with a crowd of bystanders nearby. And both involved a police patrol car stopped in a predominantly African American community. In 1965, Frye and his mother were arrested (and roughed up by officers) and an impromptu protest began. Soon South Los Angeles and Watts were being consumed by days of looting and arson in what came to be known as the Watts Riots.

The parallels between the recent events in Ferguson and previous incidents and social movements in American history are many. Throughout the 20th century, interactions between police and African Americans and other groups have led to public protest and violence. This article lists just a small sampling of the vast literature on the subject.

“Riot and Remembrance: America’s Worst Race Riot and Its Legacy,” by James Hirsch is one of several recent books detailing the long-forgotten history of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, in which armed white residents torched black neighborhoods in the Oklahoma metropolis. The event began with the arrest of a black man following an encounter with a white woman in a downtown Tulsa elevator; to forestall his lynching by a white mob, a group of armed black men (including many World War I veterans) arrived at the courthouse where he was being held. The sight of armed African Americans (in a state with Jim Crow laws) led to what amounted to a white pogrom against Tulsa’s black community.

The Tulsa tragedy is also recounted in Tim Madigan’s “The Burning: Massacre, Destruction, and the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.” Online, readers can peruse the report issued by an Oklahoma state commission in 2001.

Two decades after Tulsa, race riots swept through Los Angeles -- the so-called Zoot Suit riots of 1943 in which groups of mostly white servicemen beat up Latino youths. The California writer Carey McWilliams witnessed the violence, which also targeted black youths, and wrote about it in his ground-breaking 1949 work, “North from Mexico.” In a much more recent book, the historian Edward J. Escobar sees the Zoot Suit riots in the context of the many violent encounters with whites and police that helped forge the Mexican American community in Southern California in the first half of the 20th century. His book “Race, Police, and the Making of a Political Identity: Mexican Americans and the Los Angeles Police Department, 1900-1945,” is published by the University of California Press.

“Fire This Time: The Watts Uprising and the 1960s” by Gerald Horne is a detailed account of the events leading to the looting and arson that swept through South Los Angeles in 1965. In fiction, Walter Mosley’s 2004 novel “Little Scarlett,” is set in the community during the Watts riots. In an interview with NPR, Mosley recalled living in Los Angeles in the 1960s. African Americans were so angry at being marginalized (and of being the targets of police abuse) that even Mosely’s conservative, law-abiding father said he wanted to take a rifle and a Molotov cocktail and join the rioters (though he did not). “I wanna go out there and fight,” his father told him.

Almost four decades after Watts, Los Angeles erupted again, after the videotaped beating of Rodney King by LAPD officers in a San Fernando Valley traffic stop. The rioting began just hours after the officers were acquitted in a televised trial. But even before the verdicts came in, an official report into the LAPD led by Warren Christopher found widespread abuse in the department. Most troubling was the release of internal police text messages (sent from terminals in police cars) in which officers bragged of beatings suspects. “Capture him, beat him and treat him like dirt…,” one officer wrote.

The frustrations of African Americans in 1990s Los Angeles were also stoked by a second incident: the shooting of an unarmed 15-year-old girl in a South Los Angeles liquor store. The case is detailed in a 2013 book, by the UCLA historian Brenda Stevenson, “The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender and the Origins of the L.A. Riots.”

Of the riot itself, and the enormous psychic toll it took on Los Angeles, there are few books more moving than “Twilight: Los Angeles 1992,” which is based on Anna Deavere Smith’s one-woman play of the same name. (I was a dramaturge on the original, 1993 production at the Mark Taper Forum.) For me the highlight of Smith’s opus was then, as now, the soliloquy spoken by former gang member Twilight Bey. Riffing on the origins of his nickname and his sense of identity as a young black man, Bey says: “Twilight is that time of day between day and night…I call it limbo…So sometimes I feel as though I’m stuck in limbo, the way the sun is stuck between night and day in the twilight hours.”

Hector tweets about topics literary on Twitter as @TobarWriter

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.