You ‘fen-sucked brassy nut-hook’ ... and other Shakespearean insults

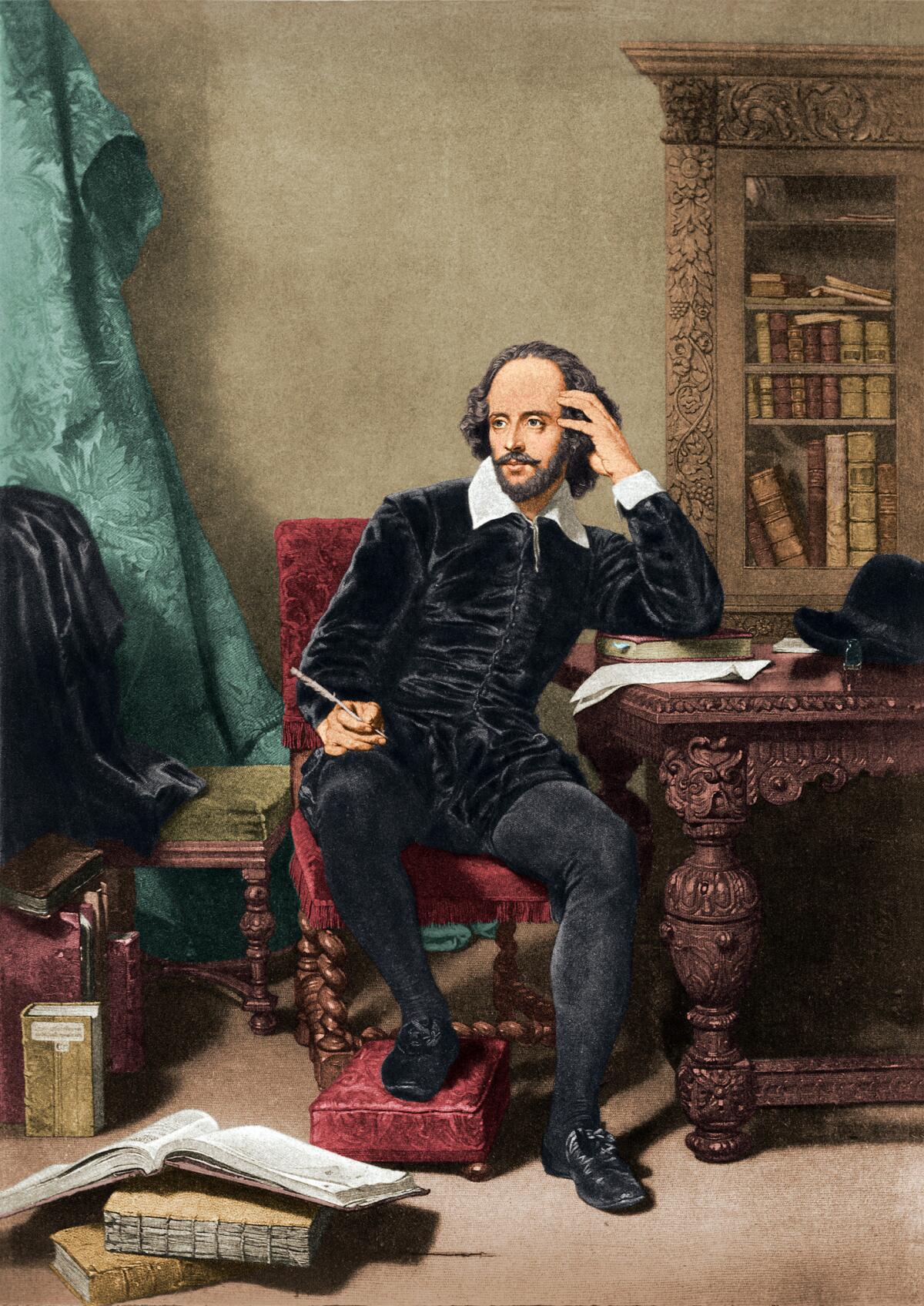

William Shakespeare ponders his next work, circa 1600.

- Share via

I first learned the pleasure of Shakespearean insults in ninth grade, when I was assigned to read “Henry IV, Part I.” My teacher was a gifted man named Greg Lombardo who instilled in our class a sense of literature as provocative, pointed, even dangerous — something that lived and breathed and mattered and bled.

For “Henry IV, Part I,” he focused on the humor, and encouraged us to stage an Elizabethan festival in class. We played music, had a feast and called each other the names we’d learned from Falstaff:

“’Sblood, you starveling, you elfskin, you dried neat’s tongue, you bull’s pizzle, you stockfish! O, for breath to utter what is like thee! You tailor’s-yard, you sheath, you bowcase, you vile standing tuck—”

Such expletives reside at the heart of Sarah Royal and Jillian Hoffer’s “Thou Spleeny Swag-Bellied Miscreant: Create Your Own Shakespearean Insults” (Running Press: unpaged, $12.95), a parlor game between hard covers, or an internet meme brought to analog life.

The idea is not a new one (a Google search yields several similarly intended websites), but the book is deftly put together: It features three sets of cards, spiral bound, that can be flipped in various combinations; on each is a derogatory Elizabethan adjective or noun.

“Foul-reeking onion-eyed fustarian,” reads one such combination. “Ruttish mammering clotpoll,” proclaims another. If there’s a flaw to this it’s that these words don’t come with definitions, although most of the time — as with “pernicious swaggering varlot” — they’re pretty easy to figure out.

In any case, I like the music of the language, not to mention the fellowship of the foul-mouthed, to which I lovingly belong.

Indeed, it was Shakespeare’s skill with an insult, especially in the banter between Falstaff and Prince Hal, that made his writing accessible to me: not as the canonical musings of an “unmannerly cullionly bed-swerver,” but rather as the street-level utterances of a “craven roguish miscreant.”

This is the Shakespeare Royal and Hoffer mean to celebrate, and their book brings me back to Greg Lombardo’s classroom, with its emphasis on Shakespeare as unfiltered, sharp and entertaining — a writer, in other words, who spoke the language of his audience.

ALSO:

Did Shakespeare write that? Forsooth, take our quiz

Denis Johnson is back, with first published story in years

Marina Warner on ‘Gilgamesh,’ the flood and what remains

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.