Bruce Berger’s ‘A Desert Harvest’ finds a story in every sunset and quirky character of the West

- Share via

“The real desert sunset occurs in that unlikely direction, the east,” Bruce Berger writes in one of his essays from “A Desert Harvest.” “It is opposite the sun that the last rays, deflected through clear skies, fall on the long, minutely eroded mountain ranges and bathe our eyes with light of decreasing wavelengths.…”

In this latest collection, consisting of both new and previously published work, Berger makes a habit of these subversive observations. He looks where others may look — at the Phoenix canals, or a simple found photograph, for instance — and then turns away, examining the subject within another context, collapsing the space between history and present, between one place and the next: “That is the revelation about desert sunsets: that the distance is so unmoored, so delicious, that you want to be there, to become that distance.” The reader can almost taste it.

As landscape without our image recedes, the wilds only deepen in their strangeness.

— Bruce Berger

Berger was raised in Chicago and educated on the East Coast, but now, at age 80, he’s a bona-fide desert veteran. His style is more poetic and less raucous than contemporary Edward Abbey; his conservationism equally felt, if not as stridently expressed. Taken in its entirety, “A Desert Harvest” renders Berger’s travels across the Southwest and down through Baja California Sur with plenty of charm and a comic sense for the surreal, but it also leaps beyond: into questions of water use or the substance of time (those foremost of arid subjects), grounding readers in the issues of the region.

In one exemplary essay, “The Mysterious Brotherhood,” Berger begins with the task of describing varieties of decayed cactus: “the barrel’s great mashed thumb, the organ pipe’s burnt candelabra, the staghorn still more like antlers when stripped of its flesh.” Death is a common preoccupation, the result of encroaching human activity in his treasured and adopted home, of his many years engaged with a land of extremes: vastness, temperature, extraordinary spines. “Cactus tells us nothing of what’s ahead, any more than the death of a close friend: all they reveal is process, but process which retains, even in human terms, immeasurable beauty.”

The history of Phoenix, from outpost through oasis to elephantiasis, is written in channeled water...

— Bruce Berger

This emphasis on process, or linked events, is one of Berger’s strengths, which appears in his style of storytelling as much as the stories themselves. The standout “Cactus Pete” takes place during multiple visits across three years to the namesake’s remote Arizona outpost. Pete claims to map the mountains on Venus, cure cancer and discover rare minerals with his trusty “doodlebug,” a mysterious contraption that seems nothing more than a spring with a rubber handle and a plastic cone (apparently tipped with uranium). Berger’s willingness to return and engage with Pete, embracing his antics, provides material for a wonderfully nutty portrait. But Berger has more in mind: He uses Pete’s mention of caliche to turn the essay inward, likening the hard mineral substance (the desert’s “false bottom”) to Pete’s persistent solitude. This new angle is where real meaning develops, as Berger finds himself navigating between “nostalgia and dementia,” attempting to understand the mixed motives of desert settlers: escapism to some pristine, primeval world, paired with a desire to make that world one’s own — to shape it.

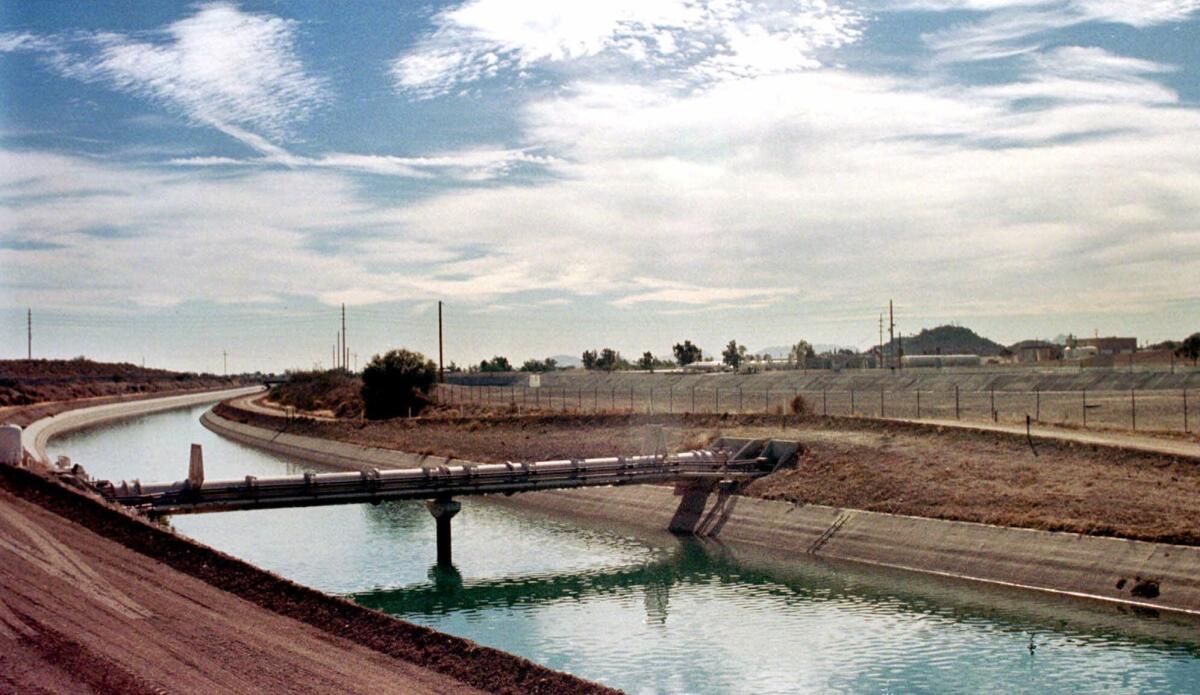

“Phoenician Shipwrecks” charts the fascinating history of the Phoenix canals, some of whose routes predate the city by nearly two millenniums. Berger begins the essay around 200 AD — when the Hohokam Indians used handheld digging tools to create more than 250 miles of irrigation lines — and then proceeds to the canals’ retrenching by settlers in the mid-1800s (for grain and alfalfa), to the citrus boom that soon followed, and into the recent past: when residential neighborhoods replaced the groves, children swam in the canals, families congregated on the banks and adventurous water skiers ploughed past at 50 miles per hour tethered to cars on adjacent streets.

“The history of Phoenix, from outpost through oasis to elephantiasis, is written in channeled water,” he writes. Now the neighborhoods are walled and the canals dredged each year to remove the tires, guns, refrigerators and dead fish that accumulate. It’s an engrossing and illuminating look at the development of one of the West’s most populous places. “Total control, once gained, was exercised, reducing the riverbed to a waste …” Berger concludes, taking his elegiac stance against Western water hubris.

These longer works are composed with the structure and pacing of good fiction or music. Berger’s background as a pianist is evident in this respect, and more explicitly in his story “The Search for Mata Hari,” in which he plays a benefit concert for the community of La Paz and searches for the lost melodies of a local maestro. Other essays riff on Willa Cather or quote Robinson Jeffers or, as when Berger returns to La Paz for the 1991 eclipse, attempt dialogue with Annie Dillard. In some of these riffs (Cather), the payoffs are great; others (as with Dillard, where it’s more mention than engagement) feel like reaches without rewards.

“A Desert Harvest” also includes a number of shorter pieces, two-page meditations on heat, sunsets, slick rock and side canyons, that verge on prose poetry:

“The addict knows that to enter a side canyon is to spin the wheel of fortune. His career is a series of tangents, out and back, out and back; like the sidewinder he advances laterally. It does no good to tell him his behavior is about as reasonable as a frayed rope, that his days are a compendium of minutiae, that he cannot see the river for its tributaries.”

The book’s final essay, “Arrows of Time,” takes up the theme of time most explicitly, despite the abstract angle. Berger accompanies a friend to a physics conference in Spain on the “Physical Origins of Time Asymmetry,” and between meals with Stephen Hawking and chasing birds in the nearby preserve, distills the behavior of quantum-level particles. The essay meanders and feels somewhat out of place in the collection but manages to provide an interesting counterpart to Berger’s reflections on geologic time in his pieces set in the Southwest. One such piece likens a wilderness trip to cycles of sleep: “Hallucination, blackout; hallucination, blackout…” As if time, like a series of dreams, were measured by the vividness of unfamiliar scenery, punctuated by “nights of sheer oblivion.” Desert hikers know that time can easily collapse or elapse in foreign proportion when surrounded by layers of ancient sediment, far from civilization, with a limited supply of water.

“A Desert Harvest” has the feel of a tributary collection for Berger; the book places him among the best of past generations to write about the Southwest. For longtime readers, though, it fails to offer much in terms of new material. The finest essays — “Cactus Pete” and “Curse of the Adorers” and “Mata Hari” — are culled from prior works. This wide range presents new readers with an excellent survey of Berger’s career, but it also leaves the collection, as a whole, spread somewhat thin; it lacks the cohesion and sustained devotion of his earlier investigations.

Nonetheless, “Harvest” is a welcome revival for an author for whom too many books have gone out of print. In Berger’s words: “The more our lands are surfeited by our presence, the more the forces that spawned us retreat from sight. As landscape without our image recedes, the wilds only deepen in their strangeness.” Berger brings us closer to the strange and encourages us to preserve it: to bridge the distance with care, or else steer clear.

::

Bruce Berger

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 272 pp., $26

McCoy is a writer from Arizona and the editor of Contra Viento, a journal for art and literature from range lands. He lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.