‘Ernesto’ traces Hemingway’s Cuba years, exploring where Papa lived, fished and drank

- Share via

Ernest Hemingway, master of the sense of place, nonetheless is identified with a surfeit of places. There are the Chicago suburbs, where he was reared. There is northern Michigan, where he fished, played baseball and first was wed. There is France, where he mingled with John Dos Passos, Gertrude Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald as a charter member of the Lost Generation. There is Spain, where he witnessed both bullfights and the murderous fights of the civil war. There is Idaho, where he hunted, wrote and died.

But mostly there is Cuba.

There Hemingway drank the local beer, breathed the local culture, angled off the local shores and wrote the most famous local book. For Hemingway, Cuba was both romance and refuge, with, of course, revolution mixed in. He inhaled its liquor and its cigars; he was a habitué of its watering holes and a captive of its Caribbean breezes. I was there, in Cuba, a few months ago. Hemingway’s footprints, metaphorical if not real, are still in its streets, in its bars, most of all in the fishing village of Cojímar, where his bronze bust looks out to the seas where he piloted his beloved yacht, the Pilar, itself preserved at his villa.

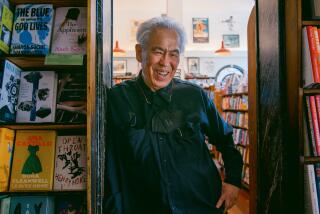

Now Andrew Feldman, having explored Hemingway’s Havana haunts and plumbed his literary and personal papers, has produced the definitive look at a definitive part of his life: his years in Cuba. The first North American invited to study in residence at the Finca Vigia Museum and Research Center, Feldman spent two years in Havana doing the meticulous research that resulted in a staggering 124 pages of footnotes.

“Ernesto” is three books in one — a biography of the writer who won both the Pulitzer and the Nobel Prize, a history of the tumultuous times that Hemingway occupied and in many ways personified, and an examination of the revolution that Fidel Castro made and that Hemingway, by and large, supported. This is a life-and-times volume about an extraordinary life conducted in extraordinary times.

Hemingway’s time in Paris coincided with the flowering of the Lost Generation, his time in Spain with the definitive pre-World War II conflict, his time in Cuba with the vital struggle between Castro and Fulgencio Batista, the American-financed, Mafia-backed autocrat.

In Cuba, his initial contribution to the world’s understanding of that island nation was a number of Esquire magazine pieces that included sage advice (sleep with the curtains open, the better to assure that the brilliant Havana sun hits you in the morning), serious counsel on drinking (which beers were best) and culinary comments (his own recipe for French salad dressing, Cuban style).

Gradually Hemingway became a Cuba celebrity and gradually Cuba began to creep into his celebrated prose. And it was more than mere fishing — that preoccupation and potent symbol — that drew him to, and kept him in, Cuba. The island was, as Feldman portrays it, “an inebriating cocktail of Old World charm and New World promise,” explaining, “Havana blossomed and offered refuge, opportunities and romance, to exiles, entrepreneurs and artists … in need of work, in search of fortune, in obstinate pursuit of paradise.”

What Feldman describes as Hemingway’s “drinking, meanness and depravity” and “the distraction of the whores and the booze” that Cuba offered produced an “obsessive delirium” that eventually led the writer to destruction. It also led him to perhaps his greatest work.

“All the years fishing in Cuba had given him a story about a humble fisherman that had caused the [Nobel Prize] Committee to recognize him and Cuba as a part of the civilized world,” Feldman explains. At around the same time, Castro’s revolution thrust Cuba onto central stage in the diplomatic world.

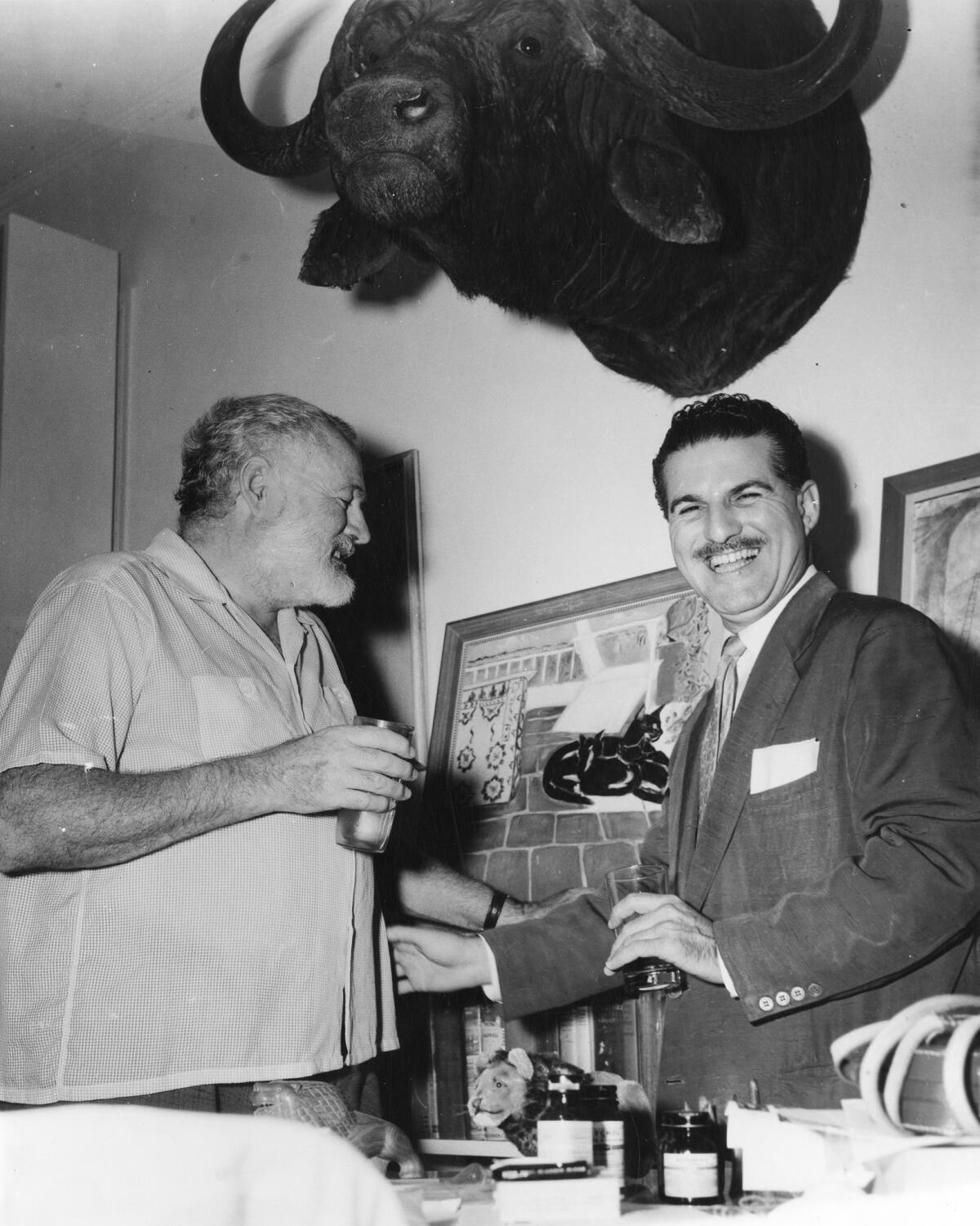

Hemingway’s relationship with Cuba’s new popular leader was casual; he backed the revolution as much out of disdain for Batista as out of support for Castro. “I believe in the historical necessity for the Cuban revolution and I believe in its long-range aims,” he said. “I do not want to discuss personalities or day-to-day problems.” At that point, of course, the only personality that mattered in Cuba was Castro.

Yet for years Castro appropriated the Hemingway myth for his own purposes. “All the work of Hemingway is a defense of human rights,” Castro said in 1967, six years after the writer’s death.

In the middle of Cuba’s and Castro’s ascendancy, Hemingway asserted, “We, the people of honor, believe in the Cuban Revolution.” Photographers weren’t humble enough to capture him kissing the Cuban flag and bid him to repeat the gesture for them. He wouldn’t do it. “I kissed it with all my heart, not as an actor,” he said. A year later he was dead.

Nearly a half-century later Castro reminisced about Hemingway’s years in Cuba, saying that he wished he had known the writer better. “I felt sincere admiration for his thirst of adventure,” said Castro, himself eight years from the grave. Hemingway might have said the same of Castro. And in this sweeping book, Andrew Feldman says much the same thing of them both.

::

“Ernesto: the Untold Story of Hemingway in Revolutionary Cuba”

Andrew Feldman

Melville House; 512 pp., $29.99

Shribman, a Pulitzer Prize winner who for 16 years was executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, is the author of three books on Dartmouth College sports.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.