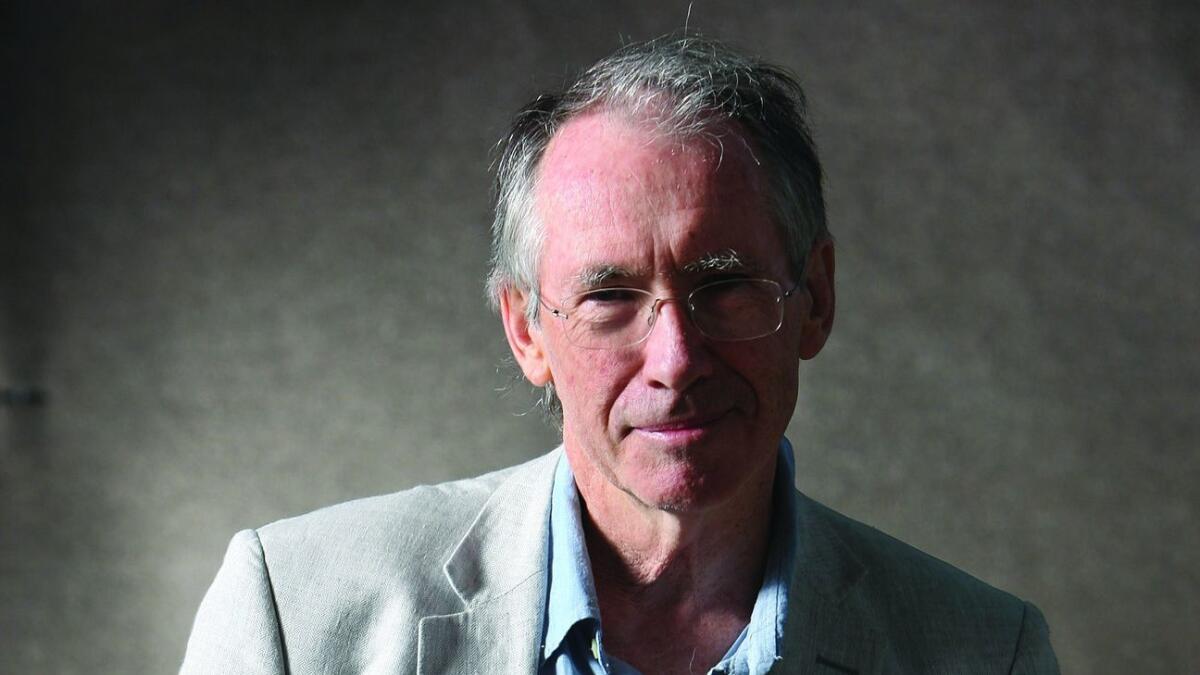

Q&A: Ian McEwan on how ‘Machines Like Me’ reveals the dark side of artificial intelligence

- Share via

Critics derided the Beatles’ 1982 reunion album, “Love and Lemons,” for its reliance on orchestration, but Charlie Friend still enjoyed the songs, the way John Lennon’s voice sounded like it was coming from “beyond the horizon, or the grave.”

Charlie Friend, the critics, the album and the Beatles reunion (two years after Lennon was actually assassinated) are all figments of Ian McEwan’s fertile imagination in his latest novel, “Machines Like Me.” The Beatles’ presence is a tiny diversion in a counterfactual novel by the author of books including “The Innocent,” “Amsterdam,” and “Atonement.” Set in a world where the atom bomb was never dropped and John Kennedy survived his Dallas shooting, the crucial alternative reality is that Alan Turing, the genius who broke Nazi Germany’s secret codes during World War II, was not hounded into suicide for being homosexual — instead, he lived to spark huge technological breakthroughs that led to an earlier Digital Age, with progress sped up by Turing’s generous open sourcing.

The novel focuses on a young couple, Charlie and Miranda, grappling with ownership of and their relationship to Adam, one of the first androids sold to consumers. “Machines” explores the moral dilemmas arising with technological advances, but also those that derive from our own basic humanity; a child’s love of play, our ability to lie to ourselves and to others, impure motives and contradictory motivations are all central to the book. The couple’s messy and emotional lives are contrasted with Adam’s constancy, for better and worse. (Adam notes that in a drama-free world run by androids, all literature would be superfluous ... except for haikus.)

“When we begin to build artificial humans or even mainframe computers to make decisions, we might want to imbue them with our best selves,” McEwan says in a recent interview with The Times. “But then we’ll find it’s rather uncomfortable to be alongside artificial people who are nicer than us, more consistent morally than us.”

But the novel also takes a big-picture look at a British society in crisis, with echoes of the mistakes made in recent times, from the Iraq War to, of course, Brexit. “The social stuff is very much one with the science and technology,” McEwan says. “It’s all seamless. Everything happening in Charlie’s household is mirrored in a society that’s beginning to wonder about things like unemployment and automation and housing.”

McEwan says he has the “old fashioned view” that, even in our screen-obsessed world, “a novel can be very effective in exploring ethical questions.”

Despite the book’s vast scope and ambition, McEwan is happy to discuss his personal take on the fictive “Love and Lemons” — he sides with the critics — and ends our conversation with the reassurance that, beyond the confines of his book, “the Beatles went on to make another album after ‘Love and Lemons,’ and it was really good.”

Charlie is a reliable narrator, but your counterfactual details create an unreliable world. Was keeping your reader slightly off-balance appealing?

Yes. We’re always predicting the future [and we’re] always wrong about it. Why not be wrong about the past?

I wanted to reflect on how very frail a construct the present days [are], how easy it would be for things to be different, that nothing is inevitable about where we are. So everything in the book is fundamentally different.

Was making Turing such an innovator a way to show what a society that is intolerant of “the other” misses out on?

He was basically driven to suicide by the primitive, stupid attitudes of his time. Everything could have been otherwise — it’s rooted in real possibilities, but it’s also a bit of wish fulfillment keeping him alive.

You sketch Charlie’s backstory very quickly but effectively. How do you figure out how much to include?

I just gave him everything he needed — he needed to have a bit of a grip on AI and to be reasonably intelligent. He has to carry the whole weight of the story.

One bit of it was autobiographical, I can now confess: the Wiring Club. When I was a teen, I toiled away for months, soldering, following these strict instructions with all these little bits, trying to make a radio. The difference between me and Charlie is that mine never worked. I never got a sound out of it. That’s a little wish fulfillment.

You’ve also long been fascinated by artificial intelligence. Why was this the time for this book?

I’ve wanted to explore for a long time what it’s like to have a relationship with what seems like an artificial consciousness. It’s like the conversation with HAL at the end of “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

We are at the beginning of something now, ready to take a huge leap forward. It is beginning to invade or enhance our lives, however you want to see it. We now have extraordinary phones in our pockets. On the dark side are the tragic deaths of almost 400 people in two Boeing 737 Max because the system is telling itself the plane is stalling when it is not. Airlines don’t like to call their jets “autonomous vehicles,” but I think this comes close.

In the last 10 years, there have been extraordinary advances in voice recognition and face recognition. The great goal now is general intelligence, to deal with situations without being told what the situations are in advance. That’s deep learning, and we have got our fingers at least on the crust of this pie.

Manufacturers of autonomous automobiles are thinking about the extent to which they protect the driver at the expense of pedestrians. So we’re at the edge of moral decisions.

Technological advances don’t always turn out the way we expect or hope.

All these new toys never quite gleam and shine the way we expect in the dusty, messy nature of life.

I remember seeing a long line in Manhattan early in the morning, and what were they lining up for? For an iPhone5. Where is it now, in the bottom of your sock drawer? We have fast trains, but they have grimy windows. And there’s the human nature the technology never quite reaches, be it messy divorces or the occasional war. Yet nothing can stop us pursuing AI. The artificial human is an ancient dream. The modern text is Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” but her monster turns into a murderer, and I think it’s more complicated — the changes bring both benefits and brand new problems.

Your characters split on moral decisions. Miranda and Charlie initially are divided on whether Adam is a machine or a sentient being. Then, at the crux of the novel, Miranda and Charlie stare across a moral divide at Adam. You had a definite opinion on the fictional Beatles’ album, so do you also have your own judgments in these debates?

I’m certainly trying not to tell the reader what to think. What I’m really hoping is not only to divide readers from each other but to split within themselves. Adam is on a learning curve during the book. I want the reader to be in Charlie’s shoes as he’s contending with someone who has a superior character and who can discuss Shakespeare with some warmth and insight. At the end, do you think Adam is a cold-blooded machine or a sentient being? That’s the issue we’re going to have, and it’s going to open up new territory for us in the moral dimension.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.