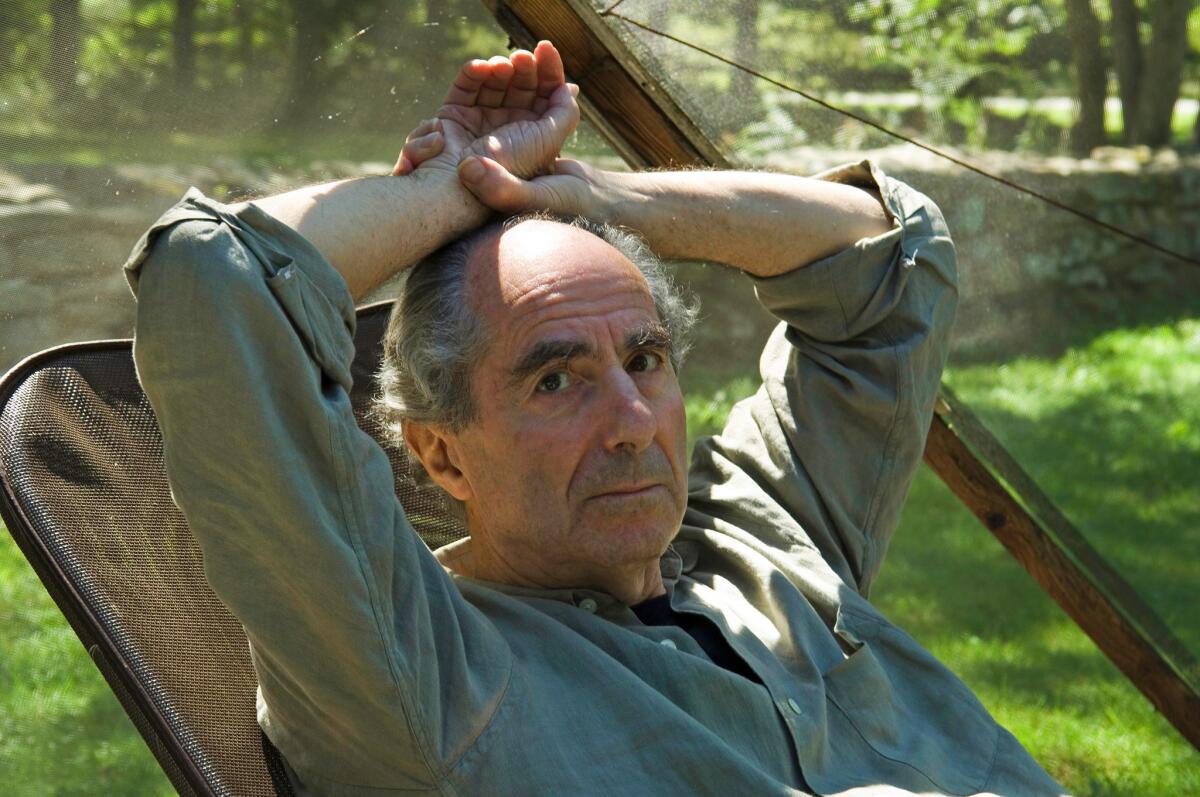

Appreciation: Philip Roth, a provocateur whose candor seared even as it reflected the American story

- Share via

Philip Roth was the first writer I encountered who reflected my image, or that of my family, back from the page.

At this point, on the day after his death Tuesday evening from congestive heart failure in a Manhattan hospital at age 85 — nearly six decades after his debut “Goodbye, Columbus” won a 1960 National Book Award — such an observation may seem like a commonplace. Let’s not forget, however, the culture from which Roth emerged and started writing, that of American (or more accurately, Northeastern) urban Jewry in the years before and after World War II.

This world was intact even in the early 1970s, when I came upon his novel “Portnoy’s Complaint” as a 12-year-old. When we think about that book, we think about the sex, all that adolescent lust and obsession; the scene in which the narrator, Alexander Portnoy, uses a piece of liver as a masturbation aid is a particularly memorable one.

But even more, I was drawn to the set pieces, especially those that took place at home. In his stoic father and his mother, who harangued and lectured like a drill sergeant, I recognized not my parents but their parents, the long line of Jewish immigration and assimilation, the fabric of their social anxiety.

“Open your mouth,” Portnoy’s mother demanded. “Why is your throat red? Do you have a headache you’re not telling me about? … I don’t want you running around, and that’s final. Or eating hamburgers out. Or mayonnaise. Or chopped liver. Or tuna. Not everybody is careful the way your mother is about spoilage.”

Roth had complicated feelings about “Portnoy’s Complaint,” which made him notorious after it was published in 1969. “I don’t have any ambivalence about it,” he told me, during a 2006 interview. “But … if you take that book out, my whole career would seem different. … I’m not sorry I wrote it. I’m not sorry I published it. But it’s influenced virtually everything anybody’s ever thought about my work.”

In some sense, Roth was right in that assessment, although it’s impossible to imagine his body of work without the novel; it’s a spindle around which much of the rest revolves. “Zuckerman Unbound” (1981), the second volume in the “Zuckerman Trilogy,” uses a “Portnoy”-esque novel called “Carnovsky,” written by Roth’s alter ego Nathan Zuckerman, as its inciting incident. The 1995 novel “Sabbath’s Theater” takes the earlier work’s “brutality,” to use Roth’s word, and supercharges it, sexually and otherwise.

At the same time, Roth was a provocateur from the beginning, in the sense that all essential artists are. His story “Defender of the Faith” ignited a firestorm when it was published in the New Yorker in March 1959 for its portrayal of a Jewish soldier using his heritage to seek special treatment from a sergeant who is also a Jew.

“What is being done to silence this man?” a rabbi wrote of Roth in response. Three years later, he was accosted by audience members at New York’s Yeshiva University.

“Mr. Roth,” one asked, “would you write the same stories you’ve written if you were living in Nazi Germany?”

The controversy is revisited in the first Zuckerman book, “The Ghost Writer” (1979), which also imagines the possibility that Anne Frank did not die at Bergen-Belsen but survived the Holocaust.

What he was investigating in such works, Roth insisted, was “the unforeseen consequence of art.” Certainly, it’s an issue that confounds Zuckerman, who became a fixture in his work. Between 1979 and 2007, Roth published nine novels in which the character appeared. He also invoked him in his first work of narrative nonfiction, “The Facts” (1988), which begins with a letter to Zuckerman and ends with his response.

“Dear Roth,” he cautions. “I’ve read the manuscript twice. Here is the candor you ask for. Don’t publish — you are far better off writing about me than ‘accurately’ reporting your own life.”

If, on the one hand, the device reads as a bit of postmodern gamesmanship, Roth was absolutely serious about the implications of narrative. In novels such as “Operation Shylock” (subtitled “A Confession”) or “The Plot Against America,” which imagined fascism coming to the United States with the election of Charles Lindbergh as president in 1940, he used himself, or a fictionalized version, as a central character. In “The Counterlife” — which is, I think, his most brilliant novel — he killed off Zuckerman and brought him back to life.

These strategies, he argued, were not experimental but practical. He built “The Plot Against America” around his own family in 1940s Newark, he once said, because he “wanted it to affect a family, but it seemed to me that if I began to invent other people, I’d get all muddled up. So I told myself the simplest thing to do, and perhaps the best thing to do, was to change just one thing — that is, the result of the 1940 election. Have Lindbergh run and win. But leave everything else in place.”

“The Plot Against America” was the culmination of a late, great run in Roth’s career: eight big novels published between 1993 and 2004, including “Sabbath’s Theater” and “American Pastoral,” which won the 1998 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, all taking on political or cultural concerns. This was a shift for Roth, whose 1961 essay “Writing American Fiction” lamented the novelist’s inability to out-imagine world events. “The actuality,” he wrote there, “is continually outdoing our talents, and the culture tosses up figures daily that are the envy of any novelist.”

If Roth, however, spent the 1960s and ’70s gazing inward, he was also looking outward, to the world. In 1971, he followed “Portnoy’s Complaint” with “Our Gang,” a vicious parody, released a year before Watergate, about a president named Trick E. Dixon, who gins up a war with Denmark so he can give the unborn the vote. Five years later, he created the book series “Writers From the Other Europe,” which introduced Eastern European authors such as Tadeusz Borowski, Bruno Schulz and Milan Kundera to readers in the West.

Even “The Counterlife,” for all its turns of plot and character, took place, in part, in Israel, where “Operation Shylock” is also set. “Part of it,” Roth told me in 2004, “is a function of age. When you’re a young man, if you’re looking back, you’re looking back to your childhood. Otherwise, you want to write about what’s going on around you. But at a certain age, I was able to look back at decades, and see that I had lived through what’s called American history.”

Roth won nearly every major literary prize except the Nobel, which became a source of consternation to him. “I suspect they’re a little bit provincial,” he said in 2013, referring to the Swedish Academy.

He was also criticized — deservedly so — for the portrayal of women in his books. In “Exit, Ghost” (2007), the last of the Zuckerman novels, the character, now in his 70s, becomes infatuated with a younger woman, objectifying her as if he were young Portnoy, a horny adolescent come to life. A similar sensibility marks his 1990 novel “Deception,” which is constructed as a dialogue between an older man and his younger lover and remains his most egregious book.

At the same time — and not to dismiss or minimize these failings — we are who we are and we write, as we must, from our own perspectives, for good and also for ill. What Roth brought to the page was a visceral honesty, an expression of the narrative of consciousness, which in the end is all we ever have to know.

I have never stopped thinking of his reflections on mortality: “The ceaseless perishing,” he laments in “The Human Stain.” “What an idea! What maniac conceived it?” Or this, the end of “Sabbath’s Theater”: “And he couldn’t do it. He could not … die. How could he leave? How could he go? Everything he hated was here.”

And yet, he did die, as we all will: It is the human condition, yes, the human stain. What other choice do we have?

“You fight your superficiality, your shallowness,” he wrote in “American Pastoral,” “so as to try to come at people without unreal expectations, without an overload of bias or hope or arrogance, as untanklike as you can be, sans cannon and machine guns and steel plating half a foot thick; you come at them unmenacingly on your own ten toes instead of tearing up the turf with your caterpillar treads, take them on with an open mind, as equals, man to man, as we used to say, and yet you never fail to get them wrong. … Since the same generally goes for them with you, the whole thing is really a dazzling illusion empty of all perception, an astonishing farce of misperception. … The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It's getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again.”

Ulin is the author of “Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles.” A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

ALSO

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.