Kim Fowley’s rock ‘n’ roll exegesis ‘Lord of Garbage’

- Share via

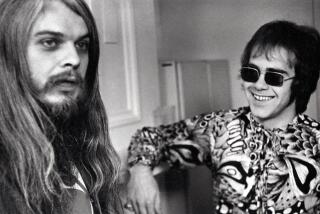

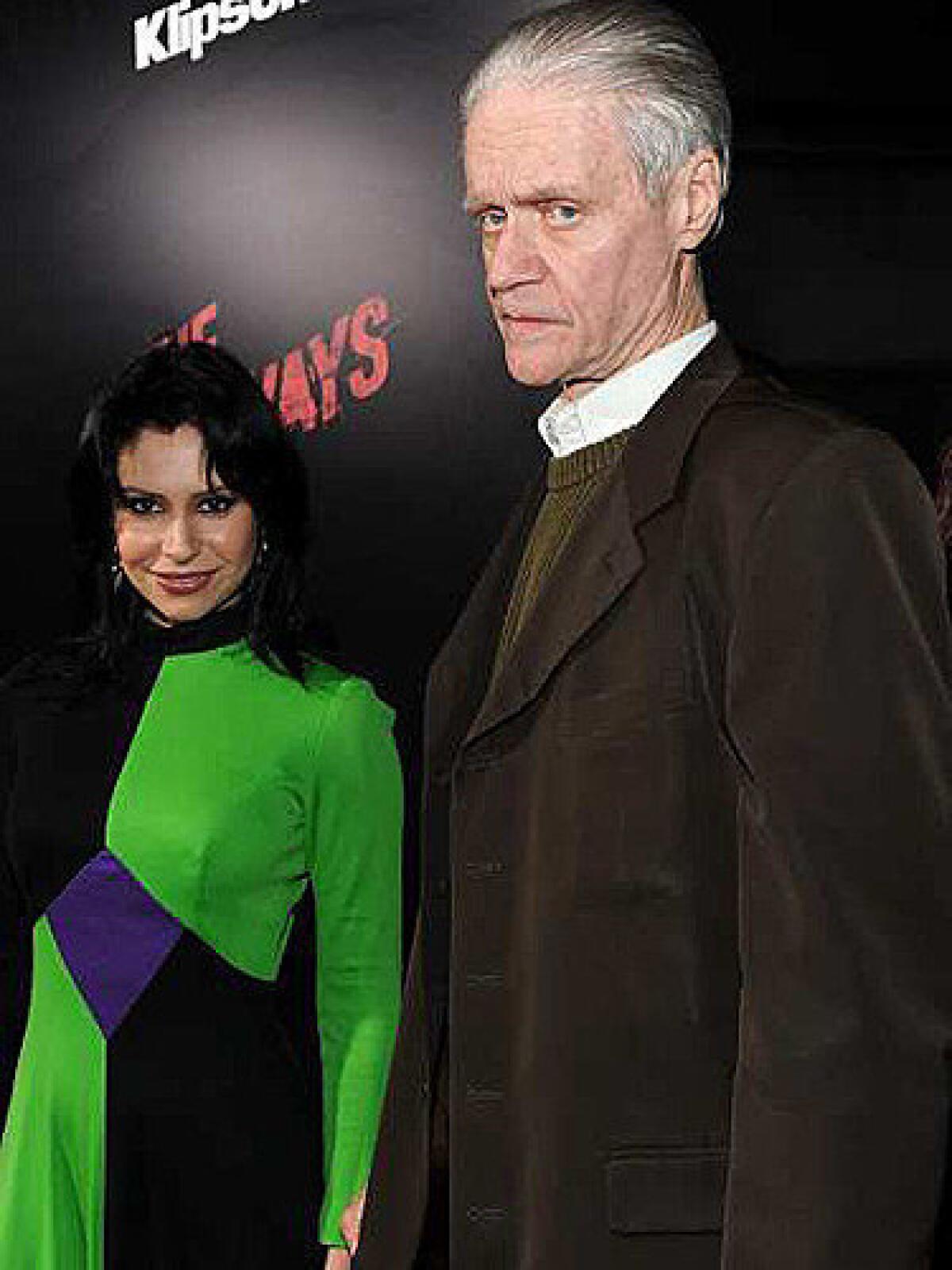

Kim Fowley came out of a Hollywood that doesn’t exist anymore, the Hollywood of Kenneth Anger and Ed Wood. Best known for cooking up the Runaways, he began to work in the music business in the late 1950s and since then has turned up in more places than Woody Allen’s Zelig, producing for Gene Vincent, writing with Warren Zevon and introducing John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band when they performed in Toronto in 1969.

Fowley turned 73 in 2012, and by his own admission has been suffering from bladder cancer, so it’s no surprise that he might choose this moment to look back. But his memoir, “Lord of Garbage” (Kicks Books: 150 pp., $13.95 paper) may be the weirdest rock ’n’ roll autobiography since … well, I can’t think of what.

The first of a projected three-volume set (Fowley claims the follow-ups have already been delivered), “Lord of Garbage” covers the first 30 years of its author’s life, from his early years bouncing between a model mother and a B-movie actor father, through a high school membership in the 1950s gang the Pagans and on to his involvement as a songwriter and producer in 1960s L.A.

How much of it is true is hard to say, exactly: Written in bombastic prose, it follows the broad parameters of Fowley’s biography while also insisting that, at the age of 1, his first words were: “I have a question. Why are you bigger than me?”

“Kim Fowley could talk at ten months,” he tells us, “could read and write by one and a half.” It’s no coincidence that he refers to himself in the third person, since “Lord of Garbage” is clearly the work of someone who considers himself larger than life. “You already know the genius music,” Fowley declares in a brief head note. “Now, know the genius man of letters.”

And yet, as self-congratulatory as that is, as sadly confrontational, it’s also, in its own weird way, slightly thrilling — not unlike Fowley himself.

Indeed, what’s most compelling about the book is not so much its air of self-hagiography but the fact that for all his posturing, Fowley does end up revealing some important things about himself.

“I became the guy / you could never be / too bad you never / took the time / to know / me,” he observes in a poem addressed to his father (the book is peppered with his poetry), writing from the perspective of a lost child, and as “Lord of Garbage” progresses, we begin to understand this as the source of his bravado, his insecurity, his self-absorption, everything.

As to how conscious Fowley is of that, I couldn’t tell you, but in the end, I’m not sure it matters.

More essential is his framing of rock ’n’ roll as an art of survival, in spite, or even because, of tragedies such as those that befell Lennon, Elvis Presley, the Big Bopper, Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens, to cite a few performers Fowley mentions here.

“I am better than Elvis,” he concludes the book. “I am better than JFK. I am better than the Beatles. BECAUSE I EXIST!”

ALSO:

Timothy G. Turner’s portrait of old L.A. finds life in digital age

Remembering John Lennon through his letters (and postcards)

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.