Column: Dear Harvard prof: Your $2,500 ticket for ‘Hamilton’ doesn’t mean price-gouging is a good thing

- Share via

Harvard economics professor N. Gregory Mankiw can be depended on to speak up for free-market principles, especially when they operate to the advantage of the privileged class. His works in the popular press have included columns defending the 1% as exceptional individuals collecting their “just deserts” and advocating the repeal of the estate tax, which he says is unfair to the rich.

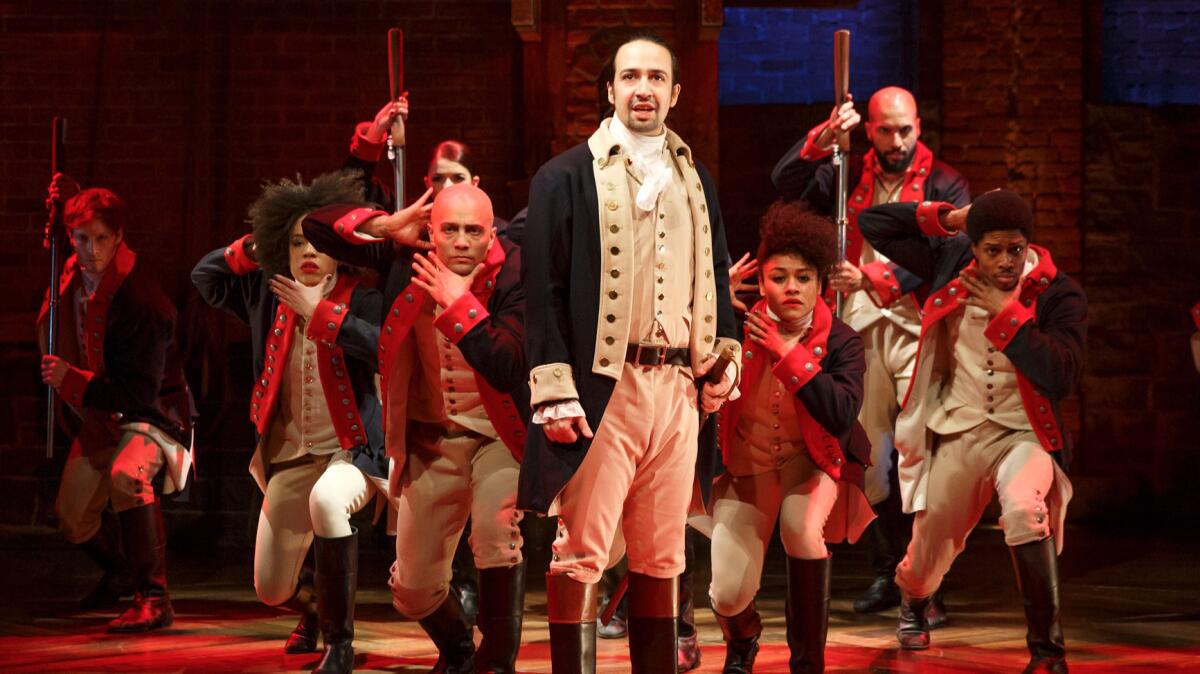

Mankiw’s latest effort in this vein tells of his quest for tickets to the musical “Hamilton,” which he was so eager to see on Broadway that he paid a scalper $2,500 each for three seats. “I paid $2,500 for a ‘Hamilton’ ticket,” he wrote in the New York Times last week. “I’m happy about it.”

The professor uses this case as a springboard to defend the law of supply and demand, or as others might label it under some circumstances, price-gouging.

I paid $2,500 for a ‘Hamilton’ ticket. I’m happy about it.

— Harvard economist N. Greg Mankiw--but is he really happy?

The issue has been getting a lot of play lately, because during emergencies — a devastating hurricane, for example — state and local officials often invoke anti-gouging laws to keep merchants from profiteering. For some reason these laws draw condemnation from conservatives and liberals alike; they’re the one violation of the law of supply and demand that everyone is comfortable attacking. After Superstorm Sandy in 2012, for instance, the usually reliable progressive Matthew Yglesias called laws stopping price hikes during disasters “hideously misguided.” All they do, he argued, is “exacerbate shortages and complicate preparedness.”

Mankiw depicts pricing as a natural instrument of the free market. “High prices are a natural reflection of great demand and scant supply,” he explained in his New York Times essay. “In a free market, in which private individuals can engage in mutually advantageous gains from trade, they are inevitable until demand subsides or supply expands.” The mutual advantage he cites is that he and his family had “no problem getting tickets” to “Hamilton,” which was good for them, and the seller of the scarce commodity got a terrific price, which was good for him. Win-win.

It’s true, he acknowledges, that “most people can’t easily afford paying so much for a few hours of entertainment,” which he labels “lamentable.”

Yet he doesn’t follow to its logical conclusion this hint that unregulated price-gouging might be a win-win-lose. That’s because he doesn’t recognize that it’s one thing to countenance whatever the market will bear when you’re talking about a luxury such as a Broadway ticket, and quite another when you’re talking about staples or public safety.

So let’s examine how price-gouging laws actually work in an emergency, and where the winners and losers are.

The defense of price-gouging most often found in the academic literature — and in Mankiw’s piece — resembles Yglesias’: higher prices are a way to ensure that a scarce item remains available longer, and therefore to more people.

If retailers were required to keep bottled water at its normal price of, say, $1 a bottle as a storm approached rather than jacking it up to $5 or $6, then the earliest customers would buy more than they needed, stripping the shelves clean before later customers arrived. Raise the price, it’s argued, and those first (price-conscious) customers would buy only what they need, leaving more for everyone else.

We’ll leave aside the question of how to know what price actually would keep people panicking about an approaching calamity from loading up. It’s more important that most such justifications of price-gouging fail to take notice of the population that can’t pay the higher prices under most circumstances. It doesn’t do a low-income family much good to find bottled water on the shelves if at $5 a bottle they can’t afford to purchase enough to tide them over the crisis. They might value the water at $5 in their extremity, but they still can’t buy it.

This is why the public typically views price-gouging in a crisis as immoral. The action substitutes one market phenomenon for another that seems much less fair: Instead of a first-come-first-served advantage, it creates a most-money-best-served advantage. Almost anyone, given sufficient foresight, can get to the store or gas station early enough to lay in a supply of water or foodstuffs or to fill up the tank. But when the commodity is priced into the stratosphere, there will be people who can’t acquire it at all.

The same rule can be invoked to analyze why it’s bad — not merely morally but from a standpoint of public health — to allow drug companies to charge market rates for life-saving drugs. When Gilead Sciences set the price of its hepatitis C cure, Sovaldi, at nearly $100,000 per treatment, it was making a free-market decision that economists like Mankiw typically applaud. In doing so, Gilead maximized its profit, but in terms that forced insurance companies and government health programs to deny the treatment to all but the sickest liver patients, even though millions suffering from the early stages of the disease would also benefit from the drug. Gilead was careful to set the price high but not so high that it would lose so many customers that its total revenues would decline. But what of those patients on the outside looking in?

Price-gouging in an emergency, then, doesn’t look like a case of the market working efficiently so much as one in which the market fails. In other words, it’s crying out for government regulation.

It’s true that pricing can help reduce shortages by steering commodities to where they’re most scarce. But that works mostly over the long term and in large-scale regional markets. When a limited market is experiencing a very brief and very severe imbalance, as in natural disasters, it merely creates inequities among consumers and profiteers among sellers.

It’s also true that getting products into a crisis zone can be more expensive than normal, so higher prices might sometimes be warranted. But that can be accommodated by anti-gouging laws that allow some flexibility, as almost all do — restricting price increases to 10% or so, or requiring a showing that higher production or transport costs justify a higher price. But allowing suppliers to raise prices sky-high just because they can get them serves no one except the profiteers.

The most curious aspect of Mankiw’s defense of price-gouging is its failure to acknowledge the role of profiteers in the mechanism he’s defending. What makes it curious is that Mankiw is fully aware that they exist: They’re the people he paid for his tickets. He writes that he was “saddened” by his purchase “in this one important way,” because he knew that about 80% of his money went not to the theater where he saw the show, or to its creators or cast, but was pocketed by the scalper, who played no role in getting the show made or getting tickets to the most deserving.

Seen in that light, Mankiw’s win-win transaction was actually a lose-lose for everyone except the scalper. Mankiw should have been more candid about who he’s defending, and admitted that he wasn’t all that “happy” about being gouged, after all.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.