Column: After an environmental debacle, a big gas utility tries to dictate terms for a cleanup

- Share via

For most of the period after Oct. 23, when a massive gas leak in at a Southern California Gas Co. storage well in Aliso Canyon was discovered, the gas company made all the right noises.

The company pledged to counteract pollution from the methane leak and help the residents of nearby Porter Ranch, who were displaced for months by the noxious fumes of escaping gas. "SoCalGas recognizes the impact this incident is having on the environment," gas company CEO Dennis Arriola wrote in a letter to Gov. Jerry Brown on Dec., 18, even before the leak was capped. "I want to assure the public that we intend to mitigate environmental impacts from the actual natural gas released from the leak and will work with state officials to develop a framework that will help us achieve this goal."

As of March 24, however, Southern California Gas has changed its tune. It doesn't care for the mitigation "framework" that was developed by the state Air Resources Board under an emergency order Brown issued on Jan. 6. It's proposing changes that would appear to make the program cheaper for itself while (according to ARB) accomplishing less mitigation than is warranted.

Any proposed mitigation program from the ARB does not itself impose any legal obligations on SoCalGas.

— George I. Minter, regional vice president, Southern California Gas. Co.

The company is also questioning whether the state has the legal authority to force it to do any specific mitigation. According to a March 24 letter from company executive George Minter to Air Resources Board Chairwoman Mary Nichols, Southern California Gas Co.'s participation in the program outlined by the board would be voluntary. The letter treats the board's plan as largely advisory, stating that it provides "ideas as to how the company might mitigate the actual greenhouse gas emissions" from the leak.

"The general tenor of their reply seems to be, 'Thanks but no thanks,'" observes Alex Jackson, legal director for the California Climate Project at the Natural Resources Defense Council. He calls it "a disappointing and shortsighted response for a company that markets itself as an environmental leader and is trying to regain the trust of the Porter Ranch community."

He also observes that Southern California Gas might be setting up for a fierce legal fight. Even if it's true that the Air Resources Board has no specific authority to impose a mitigation plan on the company, that doesn't reckon with the potential outcome of a lawsuit brought by Los Angeles City Atty. Mike Feuer and joined by Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris on behalf of a raft of state agencies. That case could be the mechanism for a court to hold the company to its "voluntary" commitments.

Feuer says he anticipated that possibility. "The gas company must be required to implement a robust climate change mitigation program, at its expense," he told me. "I'm hopeful that our lawsuit will be the vehicle to impose that requirement."

The gas company says it's not trying to wriggle out of its promises. Even before the leak was capped, a spokesman says, "SCG voluntarily committed to mitigate the greenhouse gasses released during the incident. We stand by that commitment. While SCG and ARB have different approaches, that does not lessen our commitment.... As for living up to our commitment, judge us on our actions."

Let's briefly recap the Aliso Canyon leak, which the Air Resources Board has calculated pumped 100,000 tons of methane into the atmosphere before it was capped on Feb. 18. (A final estimate won't be available until this summer.)

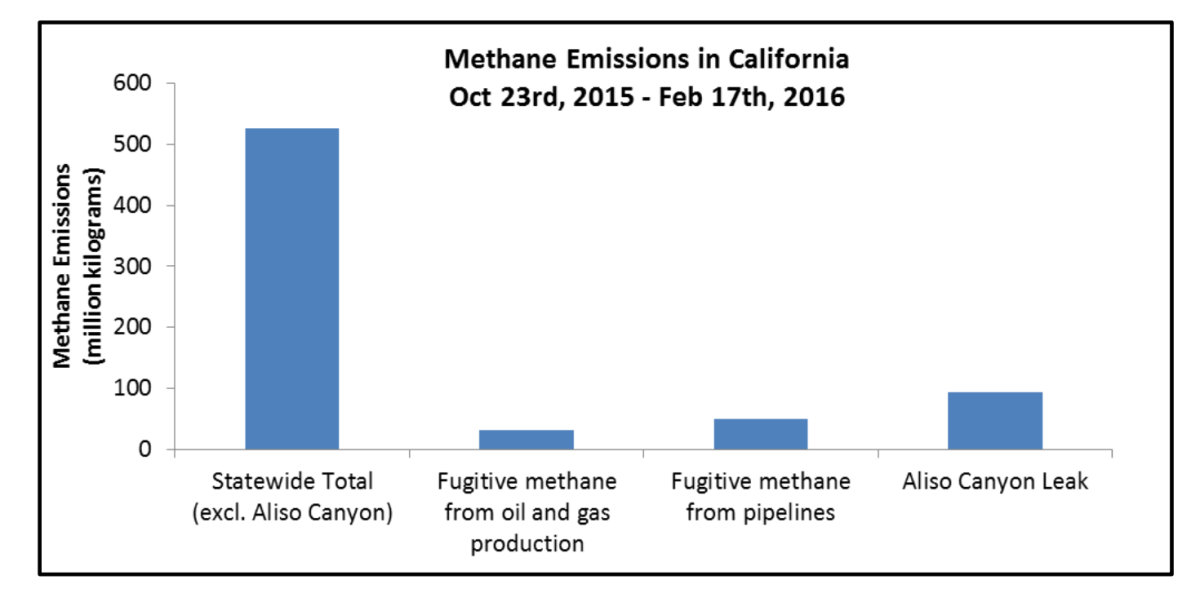

That represents a big setback to the state's climate change program and to the war on climate change generally, not merely because of the volume of escaped gas, but because methane is among the most potent greenhouse gases of all. Methane doesn't last as long in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, but in the short term it's as much as 80 times worse for the environment than carbon dioxide on a molecule-for-molecule basis. The Air Resources Board estimated through November for each day the leak continued, it added 25% to California's statewide greenhouse gas emissions, far outstripping the routine emissions from oil and gas production and pipeline operations.

That's the big picture; the small picture is the impact on the local community of Porter Ranch, a community of some 30,000 residents that was blanketed with toxic fumes of toluene, benzene and mercaptan. That's the compound added to otherwise odorless natural gas to signify its presence by a nauseating smell. Residents, including children, started reporting dizziness, breathing difficulties and nosebleeds, and hundreds had to be relocated until the well was capped.

In addition to the leak's many effects on local residents, the emissions from Aliso Canyon will contribute to global warming and its detrimental consequences for the environment.

— California Air Resources Board

There's no question that Southern California Gas is the responsible party here, and that its shareholders, not the customers, must bear all the costs of rectifying the damage. The board of its parent company, Sempra Energy, acknowledged as much when it cut the 2015 pay of Sempra CEO Debra Reed for the mishap. As I reported, the reduction was a paltry $130,000 on Reed's $16.1-million pay and she still received the biggest bonus of her executive career; but in an era when CEOs don't seem to be held responsible for anything, this was a big step.

----------

RELATED READING:

Despite the Porter Ranch disaster, the top executive over SoCal Gas is getting an enormous bonus

----------

Nevertheless, in challenging Air Resources Board's mitigation plan, the gas company essentially is acting as though the Aliso Canyon leak is just another industrial gas emission, albeit a biggish one. It's not acknowledging that this incident is not only quantitatively greater than anything anticipated by pollution regulations, but qualitatively so. That puts it at odds with the position of regulators and public officials.

"One thing on everybody's mind here is that this is an extraordinary event, not something that people would plan for," says David Clegern, a spokesman for the Air Resources Board. "There are mechanisms to deal with it, but the scale is unimaginable."

The gas company raised three major objections to the board's proposal. One involved the Air Resources Board's estimate of the "global warming potential" of the released gas. The so-called GWP is normally calculated as a multiplier of the impact of carbon dioxide, which is pegged at 1, over 100 years. This allows the relative potency of other greenhouse gases to be measured. The ARB proposed that the impact of the Aliso Canyon methane be measured over a 20-year span, which would give it a much higher impact — 84 times as much warming impact as carbon dioxide, rather than 28 times as much.

The Air Resources Board's rationale is that methane's impact is front-ended, because it dissipates quicker than carbon dioxide, so the effect of this leak should be measured in the near term. But that raises the potential cost of mitigation for SoCal Gas, so naturally it objects. Most other climate change programs use the 100-year metric, so ARB should too. But that glosses over the fact that this is a special case.

SoCal Gas also objects to the Air Resources Board's position that it shouldn't be allowed to use existing pollution control programs, such as the state's cap-and-trade credits, to mitigate the leak's effects. Its argument is that the cap-and-trade program wasn't designed to accommodate gross insults to the environment like the Aliso Canyon leak, but only routine industrial pollution; to counteract the leak, SoCal Gas might have to buy so many cap-and-trade credits that the trading market in pollution rights could be thrown out of whack.

"Allowing the gas company to use programs it's already planning or that it's legally required to do isn't really making the atmosphere whole," says Jackson of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Finally, the gas company doesn't want to be held to concentrating its mitigation efforts in California, as Gov. Brown insists. "Climate change is a global phenomenon," a company spokesman told me. "Therefore, the locations for the Mitigation Program should be flexible both in terms of where the emissions reductions occur.... The Mitigation Program should not be artificially restricted to projects within the state of California."

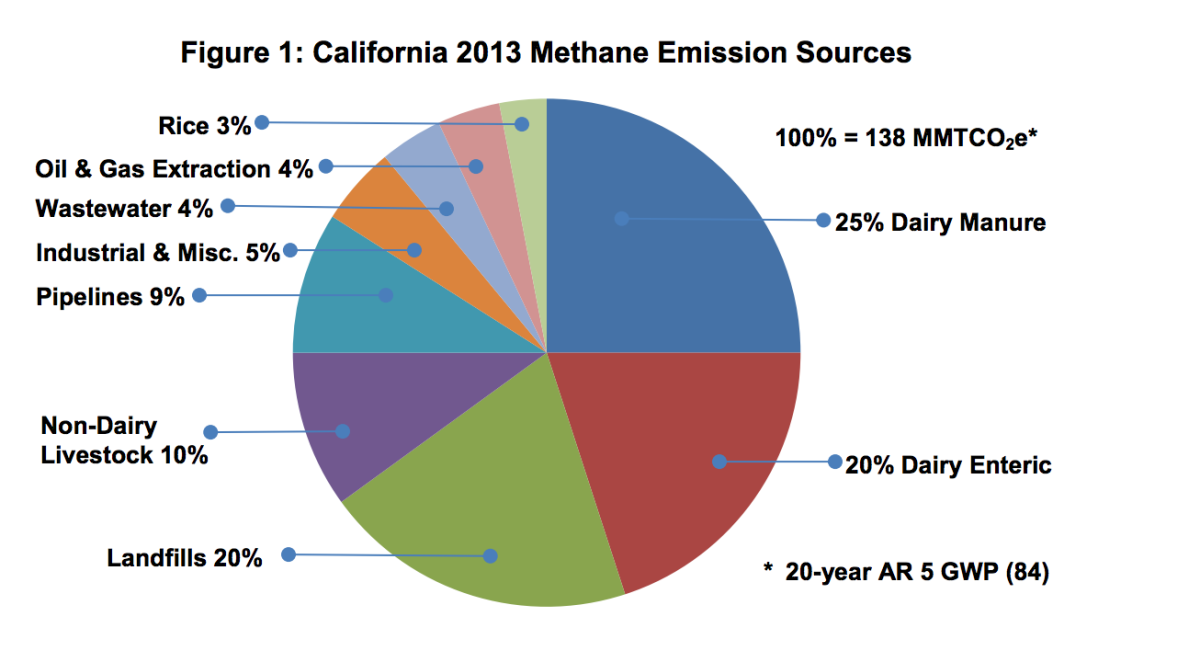

Yet there are sound reasons to force the company to focus on California. The state needs action against greenhouse gas emissions; creating programs to address methane emissions from agriculture and waste sites, the largest categories of methane emissions, is an opportunity for the state to gain something positive from SoCal Gas' fiasco.

Keeping the program within the state's borders also eases the task of enforcing the company's commitment and ensures that it's paying the price. "From the gas company's perspective," says Jackson, "they can get cheaper reductions the further afield they look."

It's only proper that state authorities have the ability to watch Southern California Gas like hawks. Though the company has made its commitment, it's already looking for ways to mitigate the cost of its own mitigation.The Aliso Canyon leak was anything but business as usual for local residents or for the greater battle against climate change, and SoCal Gas shouldn't be allowed to treat the consequences as merely the cost of doing business.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.