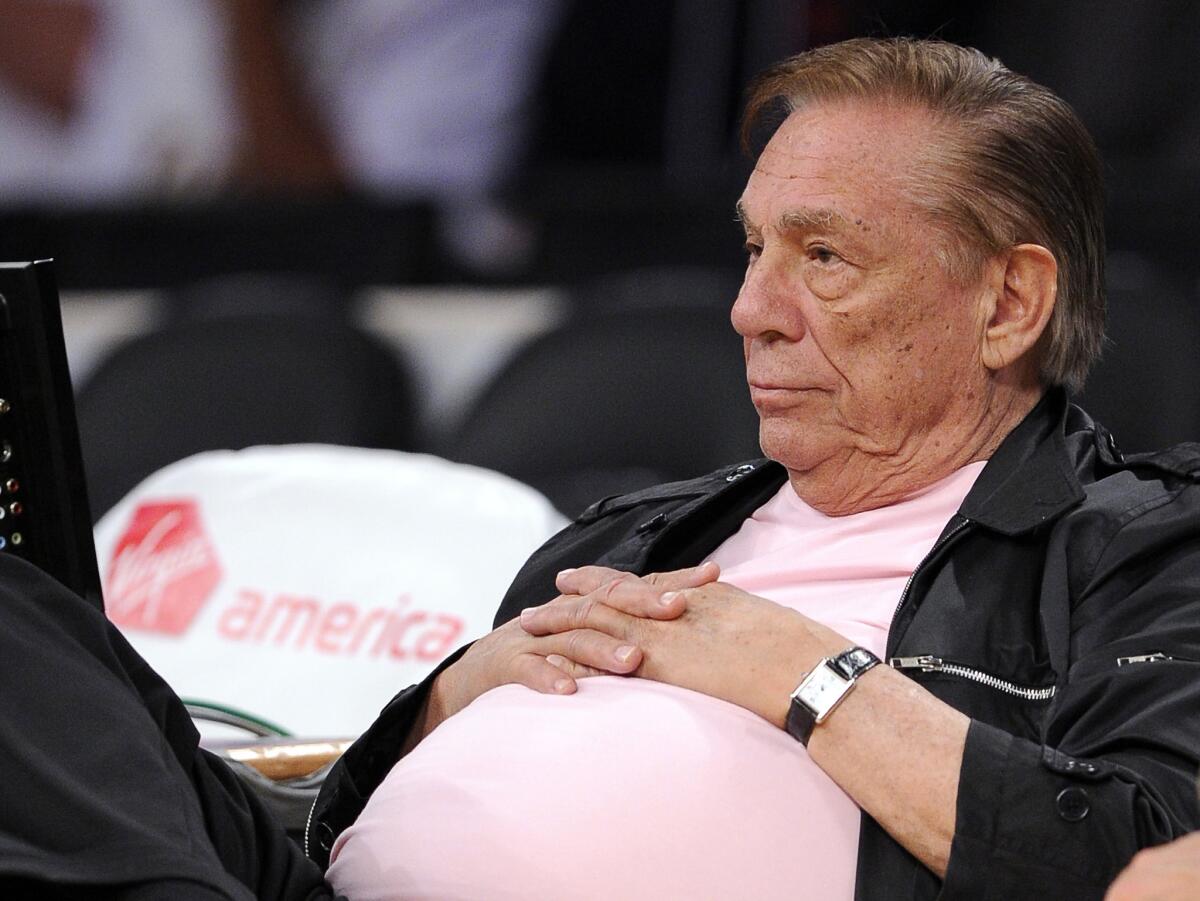

Donald Sterling and the problem of pro sports ownership

- Share via

So Donald Sterling, owner of the Los Angeles Clippers, stands accused of having made remarks of unbelievable crassness and flavored with a racism that would bring a tear to the eye of Cliven Bundy.

Are you surprised? Me neither. Sterling’s record of difficulty with racial issues is well-documented, including two lawsuits (one from the federal government) alleging racially discriminatory rental practices at his real estate properties. He settled both for millions.

Then there was the lawsuit from long-term Clippers general manager Elgin Baylor accusing Sterling of racial and age discrimination; Baylor lost his case in a 2011 jury trial. Another accusation of racist rhetoric, attributed to veteran college basketball coach Rollie Massimino, dates back to the 1980s. And there’s more.

The fact that Sterling has survived all these prior dustups -- and the betting here is that he’ll survive this one, too -- says less about Sterling himself than it does about America’s unhealthy relationship with its pro sports tycoons and about the unhealthy structure of pro sports leagues.

Let’s start with the character of the men (and a few women) who have been members of this tiny club. Almost all of them are self-made businesspersons or inheritors of great wealth. Either way, they’ve come up in the world unaccustomed to having their personal whims thwarted. As my former colleague Tom Mulligan reported in a 1996 profile of Sterling, his real estate wealth gave him “the luxury of being able to say no to anything and anybody.”

People in that position have difficulty with impulse control, not to mention empathy with other humans. Add the slavish sycophancy that comes to owners of businesses (like sports teams) that are commonly mistaken for civic assets, and their concerns about how they’re perceived by the public evaporate completely.

Why should a pro sports magnate care about his public reputation when municipal leaders are willing to throw billions of dollars his way to build a new stadium or arena? And if his local leadership balks, there’s always another city willing to step in.

The structure of pro leagues, which are basically alliances of independent entrepreneurs, exacerbate these people’s worst instincts. Consider the behavior that the leagues have found acceptable.

Wrecking a team for profit? Jeffrey Loria has done that with baseball’s Miami Marlins. He’s still an owner.

Abandoning a loyal fan base for profit? Bob Irsay of the NFL Baltimore Colts did that, infamously moving the team to Indianapolis in the dead of night. His son Jim is still the owner of the team.

Failing to invest for success on the field? Lots of guilty parties here, including Peter Angelos, whose Baltimore Orioles have made it into the postseason three times in his 21 years of ownership. Sterling is a standout in this category: Since he acquired the Clippers in 1981, it’s had five winning seasons, going 930-1,646 -- a winning percentage of .361.

Felonious activity? Eddie DeBartolo Jr., owner of the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers, pleaded guilty to a federal felony in connection with the solicitation by former Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards of a bribe for a casino license. DeBartolo relinquished control of the team, but this year he was a finalist for the NFL Hall of Fame, and he still hankers for a return to NFL ownership -- a goal that several owners say they would favor.

Racism? Leaving Sterling aside, Marge Schott, onetime owner of baseball’s Cincinnati Reds, had a long history of racist and anti-Semitic remarks. Baseball finally suspended her as the team’s principal owner, but she retained a financial interest.

Leagues are reluctant to take firm action against owners for several reasons. One is that their authority to do so, absent some truly egregious act, is murky -- even overt racism is a judgment call. Figuring out what to do with an orphaned team is a headache. And fellow owners are loath to lower the bar, possibly because not a few of them have unsavory histories of their own to worry about.

Success on the field can provide protection against judgment -- witness the reverence still afforded DeBartolo in San Francisco, where his team won five Super Bowls. But it’s not necessary -- witness Sterling’s dismal record.

The pro sports leagues can’t be trusted to police their own team owners. So what’s the solution to their noxious behavior? It can only come from the communities. Politicians inclined to hand over public land or facilities to pro teams have to remember that the people they’re giving gifts to are, as a species, some of the most contemptible human beings in creation.

They’re arrogant, manipulative, greedy and capable of the most inhumane and abusive behavior, individually and collectively. If you doubt that they will take advantage of anyone in a defenseless position, take a look at how the NFL teams, as a group, have mistreated their underpaid cheerleaders, who are unprotected by a union. (For that matter, consider how they’ve treated their own injured players, who are protected by a union agreement.)

But nothing will prompt the leagues to take action against a misbehaving owner until and unless they perceive that the behavior is costing them money. An owner who loses a stadium deal? That would do it. An owner who provokes a fan boycott that actually empties the stands? That would do it.

What does that mean for Donald Sterling? The Clippers play in a private arena, so the city of Los Angeles doesn’t have much sway over the team. Magic Johnson has said he’ll boycott the Clippers as long as Sterling is the owner, so possibly there’s a seed of a community revolt in that.

But don’t count on it. The smart money says Sterling will wriggle out of this controversy. He’ll say that the recorded conversation at the heart of the latest accusations was private, that he misspoke or uttered his slurs in a weak or emotional moment, or that it isn’t him at all. He’ll point to his record of public philanthropy. He’ll find a complaisant television talk show host to give him a platform for a heartfelt public apology.

Already, the Clippers have alleged in a statement that the tape of Sterling’s comments was released by a woman involved in a lawsuit with his family. And the statement asserts that “what is reflected on that recording is not consistent with, nor does it reflect his views, beliefs or feelings. It is the antithesis of who he is, what he believes and how he has lived his life.”

Sterling will point to the Clippers’ winning record and postseason appearance this year. If the team beats the Golden State Warriors on Sunday afternoon and returns for Tuesday’s home game in a position to win the series, well, that’s what pro sports is all about anyway.

Isn’t it?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.