From super agent to Disney castoff, Michael Ovitz recounts his epic fallout with Michael Eisner

- Share via

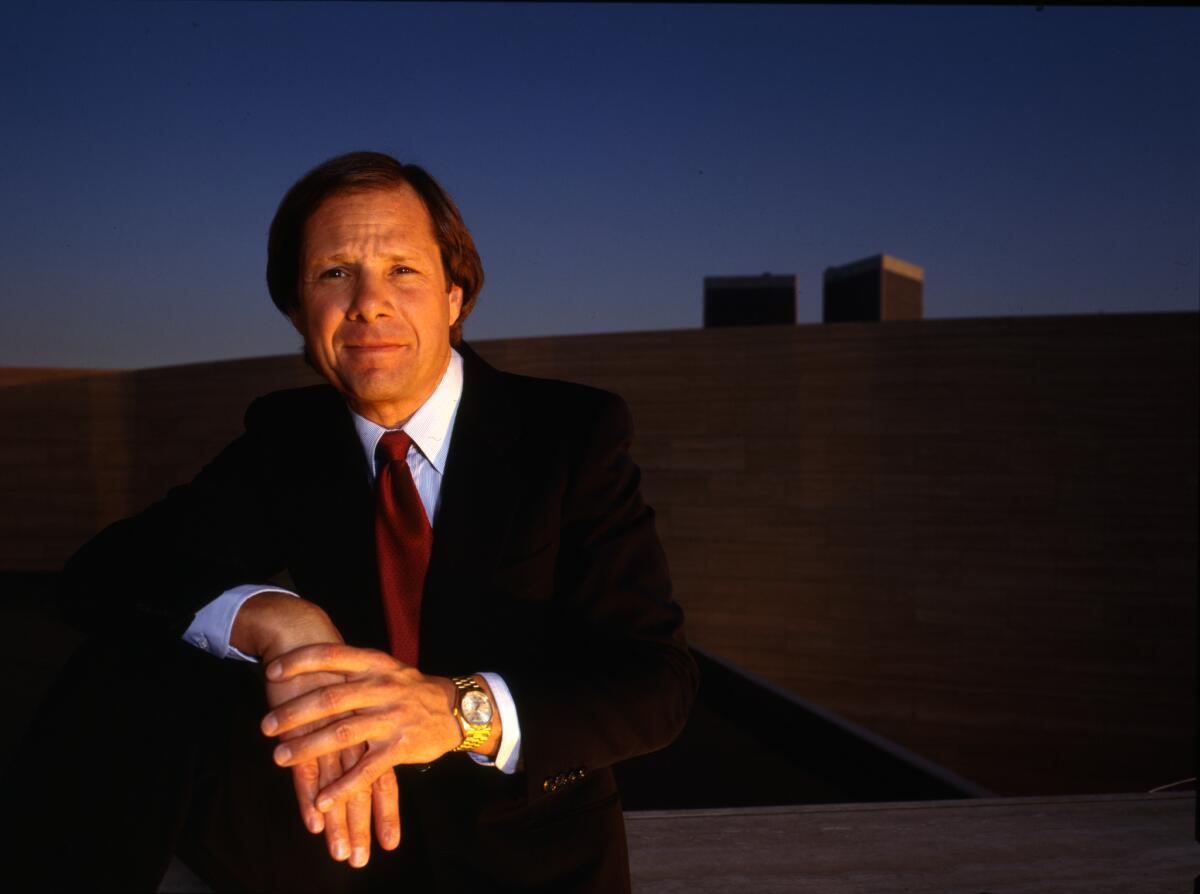

To some, he was a brilliant negotiator and pioneering agent who guided the careers of such top talent as Steven Spielberg, Meryl Streep and Dustin Hoffman. To others, he was a ruthless tactician who would not let anyone stand in his way. In his memoir “Who Is Michael Ovitz?” the former super agent offers his own take on how he became one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. The memoir, due out Tuesday, traces Ovitz’s remarkable career as co-founder of Creative Artists Agency and his brief, ill-fated tenure as president of Walt Disney Co. Disney CEO Michael Eisner handpicked Ovitz in 1995 to be his lieutenant at the Burbank-based company. But Ovitz’s partnership with Eisner was doomed from the start. In a chapter entitled “Number Two,” reprinted here with permission from Portfolio (a member of Penguin Random House), Ovitz recounts what went wrong.

In August 1995, on a family vacation in Aspen, Michael and I took a hike to hash out my role and title. For some time he’d been saying that only two people in L.A. could replace him: Barry Diller and me. After his [heart surgery] operation, he sent a letter to that effect to his board. A number of directors told me I had their support. More than one added that they hoped I’d bring CAA’s team-first culture to Disney, where backstabbing was a blood sport. But Sid Bass, the company’s largest shareholder, would prove to be entirely in Eisner’s pocket. Naive and easily manipulated, he was a rubber stamp for whatever changes Eisner wanted to make — which turned out to be none.

It worried me a little that Michael’s plan for us was in constant flux. First we were going to be co-CEOs. Then he floated the idea of staying on as chairman and making me sole chief executive. More recently he’d talked about making Disney and ABC separate operational entities, one for each of us to run. Titles didn’t really matter, we agreed. We’d be full partners, like Goizueta and Keough at Coca-Cola or Daly and Semel at Warner.

As my September start date neared, Michael decided to keep the CEO title for himself and make me president and COO, reporting directly to the board. He’d had the same arrangement with Frank Wells. I asked how he planned to insert me over his incumbent execs. “They all work for me,” he said, “so they’re all going to work for you.” Fair enough. I assumed I’d start as number two and move up from there.

Now, in Aspen, he informed me that he was tweaking our arrangement. Until I “earned” being COO, I’d report to him rather than the board. I needed time, he said, to transition from a small private company to a gigantic public one. I knew I faced a learning curve, but I had counted on my friend to support me in public and advise me in private. He assured me that time would resolve the issue, but I felt baited and switched.

That was the first yellow flag. The second came a day or two later when I was flying on a Disney jet to L.A. with Joe Roth, Michael’s studio chief and a longtime client of mine. I’d made Joe’s original deal with Disney at a time when the studio needed more producers on the lot. Now he told me he was worried that I’d outflank him by developing movies with CAA clients. I assured him I had no such thing in mind. (To avoid crowding Joe, I would stay out of film production at Disney.) What shook me was discovering that Joe had wanted my job for himself, so he’d be rooting for me to fail.

The third flag popped up that evening at Eisner’s house in Bel Air, where I went to review the press release about my hiring. As Michael greeted me in his dining room, I was surprised to see Stephen Bollenbach, Disney’s CFO, and Sandy Litvack, the company’s general counsel and a man widely detested by Eisner’s subordinates. We’d barely shaken hands when Bollenbach declared he wasn’t reporting to me. Litvack then said the same thing. In the tense silence, my first thought was that Michael had orchestrated the showdown to clear the air — a move I might have made in his place. I waited for him to back me up and set Bollenbach and Litvack straight. But he averted his eyes and let me hang there.

I tried to engage my new colleagues and explain that I was going to be COO and that they’d report to me but it would be collegial — that I was just there to help. But they were adamant. I didn’t know that Michael had recruited Bollenbach by implying he’d replace Frank Wells. I didn’t know that Litvack had his own designs on the job; Eisner had always dismissed him to me as “a functionary.” One came out of real estate and the other out of litigation. Neither had any experience with talent, or with making and distributing films, television, or books.

When Michael and I took a break in his son’s bedroom, he seemed as flustered as I was. He stroked people by reflex, promising everyone autonomy, but obviously we couldn’t all have autonomy. A menschy CEO would never have let Bollenbach and Litvack into his house, let alone allowed them to ambush me without a word of reprimand. I pleaded for Michael’s support. He assured me he’d work it all out. “Steve and Sandy don’t have your creative background,” he said. “You’re the one for this job.”

I stepped out to call Judy. “Michael just threw me under the bus,” I told her. “No matter what I do, I’m going to fail in this job. I think I just made the biggest mistake of my career.”

The next day I assembled my brain trust and posed the nuclear option: should I call the whole thing off? Bob Goldman was pessimistic but stopped short of telling me to bail; Sandy Climan was on the fence; and Ray Kurtzman thought I should make the best of it. I agreed, glumly. I was too far down the road to turn back, particularly after having gone so far down a similar road with Universal. But from that evening at Eisner’s house on, I had a ball in the pit of my stomach that never left.

Eisner was working on a memoir with a writer named Tony Schwartz. Minutes after I called him, following my meeting with the brain trust, to say that I was in, he told Schwartz exactly what I’d told my wife the night before — that he’d just made the biggest mistake of his life. He wondered if he could take his offer back. I wish he had.

“That's the stupidest idea I've ever heard.”

— Michael Eisner

In a big company you’re defined by whom you report to and who reports to you. With Michael cutting me off from the board and boxing me in from the executives below, I felt pinioned from the start. Taking meaningless meetings would get me and Disney nowhere. But there was another way to build the company — through M&A.

I’d come from a racing yacht called CAA that I could turn on a dime. Now I was on the Titanic and I needed to steer it before I’d made any friends in the bridge. Which alarmed the officers in the bridge, which panicked Eisner, which freaked me out and made me steam full speed ahead into the iceberg. That’s the short version.

My first week on the job, I reached an agreement with Brad Grey, a top-notch TV producer and talent manager who would later run Paramount. In return for exclusive rights to his productions and an open line to his artists (from the Saturday Night Live gang to the writers who’d create The Sopranos), Brad would get a production deal at our film studio. It would be a major statement to the creative community. But neither Joe Roth nor Bob Iger, who ran ABC, wanted Brad on the lot. Eisner backed his lieutenants without explaining why. No deal.

The next day I tackled Michael about the Tele-TV concept he’d ripped off from me. Though I’d never been happy with his duplicity, now we could start fresh. Why not combine Tele-TV and the copycat version he’d established with Americast and GTE and pull in the same direction? He dismissed the idea.

Over the next several months I put forward new ideas in publishing, music, digital technology, and international operations. I had tentative deals with Tom Clancy, Michael Crichton, and Stephen King — three of the four bestselling authors in the world — for exclusive rights to their books, movies, and miniseries. Disney would be a publishing powerhouse. Michael said no. Then I brought him a handshake agreement to buy G. P. Putnam’s Sons, Clancy’s publisher, for $350 million. He wasn’t interested. (Later snapped up by Penguin and subsequently merged with Random House, Putnam is now worth well over ten times what we’d have paid for it.) I arranged for my longtime client Janet Jackson to jump from Virgin to Disney in a seven-album, $75 million deal. It could have pumped new life into our Hollywood Records label and fixed Disney’s cheapskate image. “We’ll grow our own stars,” Michael said. Hollywood Records would not grow a single star under Eisner.

I flew to Tokyo to see Masayoshi Son, the head of the tech-focused SoftBank, about his minority stake in Yahoo, then the chief Web portal. Based on preliminary discussions with Eisner and other board members, I was plying a strategy to get Disney online. I could see our cartoon characters leading millions of Yahoo home page viewers to news and weather sites while selling Disney merchandise and promoting Disney movies.

To my surprise, Son said he would sell his shares for a mere $250 million. Given what was about to happen to the internet, his stake would have been a bargain at quintuple the price. Fired up, I rushed from lunch to the airport, flew ten hours to LAX, and went straight to the office at 10:00 the next morning — I didn’t even shower or shave. I entered Eisner’s inner sanctum to find him with Stanley Gold, an influential Disney board member. “You’re not going to believe this!” I told them. “We have a shot to buy Masa Son’s piece of Yahoo.”

“That’s the stupidest idea I’ve ever heard,” Michael said. Wheeling into mountaintop mode, he pronounced that people went online for information, not entertainment. It wasn’t just that he was wildly wrong; it was that my supposed partner was deliberately embarrassing me in front of Stanley. Because my vulnerable spot, as Eisner knew, is my sense of dignity, his tactic was devastating. Humiliated, I left without another word.

With 80 percent of Disney’s revenue deriving from North America, I tried to shift us toward a healthier domestic-foreign split. I met in Beijing with Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji, China’s leaders, on a host of issues of mutual interest: a Disney theme park, joint film and TV production, piracy and intellectual property. On the strength of this budding relationship, I had high hopes for a Chinese Disneyland and a busy pipeline of coproductions. The timing was perfect. We’d be planting the Disney flag early enough to get in on China’s economic explosion. But Michael showed no interest and the initiative died, an untold waste.

Michael contended that Disney was an “operations company,” making acquisitions secondary. While I knew Michael liked to stay in-house, the ABC merger had given me hope. Before we agreed to work together, he had acknowledged that Disney needed to grow in every area I was now addressing. And Michael knew exactly what he was getting when he got me: a deal maker.

Early on at Disney, I got a call from UCLA Hospital. They had been about to sew up a hole in Jay Moloney’s heart, a congenital defect, when they’d discovered “heavy drugs” in his blood. They’d canceled the surgery, then called me because Jay had listed me as his emergency contact. I was touched that Jay still thought of me as a surrogate father, even as I suddenly made sense of his increasingly strange behavior over the past few years: the days he’d miss work and then show up, bruised and out of it, with a story about having been mugged.

A few months later, David O’Connor called me, nearly frantic: Jay was holed up in his house on Mulholland Drive, lost in drugs. David and I went up there together, kicked three hookers out of the house, and flushed a lot of cocaine down the toilet. Jay was remorseful, self-hating, a wreck. “I love you, Jay, you’re like a son to me,” I said. “But I’m not going to stand by and let you kill yourself.” “Okay,” he said, wearily.

I had distanced myself from Jay when he began to fall apart. I felt he should have control over the drugs, rather than vice versa; that he was betraying himself, and was therefore no longer worthy of my affection and support. That was a bad mistake, and looking at him now, so defeated, I wanted to do anything I could to make him better. I found myself wishing fervently that I’d paid more attention to Jay’s neediness, his wounded side, from the beginning. He was so talented and I was so laser focused on my own needs that I had just let him go, let him make money for all of us, let him chase the misbegotten dream of becoming just like me.

David and I drove him down the hill to Turner’s, the liquor store on Sunset, where I had a UCLA internist I trusted waiting in a car in the parking lot. We marched him to the doctor’s car, and Jay reluctantly got in — then tried to scramble back out. We held the door closed, remonstrating with him through the glass. Finally, he gave up, and let himself be driven to UCLA to get cleaned up before going into rehab.

He went through rehab five times over the years, but each time he came back a little further away, a little more lost. CAA finally asked him to leave. I would later offer him a job with me in my next gig, at AMG; I thought that if Jay rededicated himself to others it could help bring him back. But he declined; he was too far gone. In November of 1999, I got a call from David O’Connor: Jay was dead. He’d hung himself in the shower of his home. He was thirty-five. I was shocked and devastated, but not really surprised. At his memorial service, I called him “a passing comet” who “lit up our lives.” But it was Bill Murray, as usual, who nailed it. Looking out at the mourners, all of nineties’ Hollywood, Bill said, “There are so many people sitting here today who I would so much rather be eulogizing.”

“In my first week on the job, Eisner told me to fire Bob Iger.”

— Michael Ovitz

As the dispute over Jeffrey Katzenberg’s unpaid compensation headed for the courts, Michael let me try to settle it. I’d be dealing with both Jeffrey and his friend and adviser David Geffen, which would be tricky. David and I had fallen out back in 1980, when he was producing Personal Best and our dispute over writer-director Bob Towne’s compensation delayed the start date. I respected David’s considerable achievements, but hard as I tried to stay on his good side, he seemed to feel slighted that I didn’t confide in him or, perhaps, defer to him. I would have been wiser to befriend him and take his counsel — given his intellect and influence, that was an error in judgment. But I preferred keeping my own counsel.

This once, however, our interests were aligned. We arrived at a figure of $90 million — a fabulous deal for Disney, given Jeffrey’s contributions to blockbusters such as The Lion King. I brought the agreement to Eisner, who turned it down flat. It was left to me to break the bad news to Jeffrey, a further mortification. (The parties later settled out of court for a reported $250 million.)

The guy who closed everything was now closing nothing. I couldn’t discuss the problem with anyone without looking even weaker, so I revved up, working harder than ever, sleeping only four hours a night, pushing for a breakthrough like a man possessed. Jane Eisner called me in a fury: “Your crazy work ethic is pressuring my husband. He’s putting in too many hours. It’s against doctor’s orders!” I believed if I could get one thing to work, one new artist or acquisition, maybe everything would turn around. If insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result, I had become stark raving mad.

I made plenty of mistakes. I came in like a whirlwind, far too frenetic for Michael’s taste. (He used to complain to me about just that quality in Frank Wells.) In trying to keep the Brad Grey deal confidential, I failed to build consensus before bringing it to the boss. I was at sea in Disney’s hierarchy and fiefdoms. It was hard to downshift from CAA, where I did as I pleased at my own headlong pace.

But my instincts were good. In a 2005 article headlined “What if Eisner had listened to Ovitz?, Fortune looked at six of my proposals. The magazine judged one, a merger of Sony and Hollywood Records, a long-term negative (I’d argue that the advent of digital music would now make that deal a winner). My plan for an NFL team in L.A. was called a push. But the article rated four other ideas (Yahoo, Putnam, the Katzenberg settlement, and a joint venture with Sony PlayStation) as big positives for the Magic Kingdom had Eisner said yes.

I did get a few things done when I immersed myself in the nitty-gritty of operations. I came up with the idea for ABC’s One Saturday Morning, a two-hour block of children’s programming they launched after I left. I mediated for executives who were at odds with Michael or one another or both — a tidy subset at Disney headquarters, which was hardly a Magic Kingdom. When Tim Allen walked off Home Improvement, putting a syndication deal worth hundreds of millions into jeopardy, I met with him and worked things out.

But for the most part I ran in place. My directives were ignored; my suggestions vanished down the memory hole. More than one person at Disney later told me that Eisner went around me to everybody who mattered. He directed Larry Murphy, who led the planning group, to report on our meetings but to sit on anything I proposed. He did the same with Dean Valentine, head of TV animation, who fawned to my face while feeding the press anonymous negative quotes about me. Just humor him, Michael said, and they did.

Unable to quit without losing my severance, I was a lame duck awaiting the ax. In mid-September 1996, Sandy Litvack barged into my office. “Michael doesn’t want you at the company anymore,” he said, triumphantly. “Go tell Michael to come tell me himself,” I said. After a twenty-something-year relationship with my so-called friend, I thought I deserved to be fired face-to-face. Michael didn’t appear.

He had volunteered to throw the party for my fiftieth birthday that December. ‘Hang in till then,’ I told myself, ‘and perhaps not all will be lost.’ He repeatedly suggested that we’d figure out a soft landing so I wouldn’t be totally embarrassed in the community: I’d stay on Disney’s board for a year after leaving management, or serve the company as a consultant. (He reneged on those promises, too.)

Three days before my birthday, Michael summoned me to his late mother’s apartment in New York to sign off on my resignation “by mutual consent.” He said he still wanted to stay friends and host my party — a bizarrely crazy idea that wouldn’t happen, of course, but one that was quintessential Eisner. I shook his hand glassily and walked out. Twenty years later, I still have no interest in ever sitting down with him again. Even if he made the most spectacular apology in the world, he’s incapable of true change. By the time I returned to my apartment, three blocks away, my letter of resignation had already been hand delivered. It was signed by Sandy Litvack.

I spent a quiet birthday at home in Brentwood with Judy and our three children. For once, I didn’t answer the phone. Then I flew to Aspen for a week to be alone and think. I was livid with Eisner and furious at myself. I felt awful, worthless, an utter failure.

Intellectually, I knew it wasn’t my fault. From the moment of the ambush in Bel Air, Michael had withheld the support he’d promised. It had been deliberate, and cruelly so. But I couldn’t process what had happened intellectually; the emotions were too strong. Betrayal really sets me off. I had to walk out of the movie Betrayal — based on the Harold Pinter play about a man who carries on a long affair with his friend’s wife — because it stirred up so many churning feelings. My dad once told me, “You give your all to your friends and clients, and you expect the same back. But you’re not going to get it. They’ll betray you. I was in sales — I know.” I had argued with him then, but now I decided he was right.

A week of hard thinking about Michael Eisner wasn’t nearly enough. It took me half a year to feel normal again, and longer than that to make sense of Michael’s behavior. I think he was sincere when he wooed me, in his weakened postsurgical state. But then Michael recovered. And the better he felt, the worse I looked to him. I was four years younger and vastly more energetic. Ovitz the Savior became Ovitz the Rival.

In my first week on the job, Eisner told me to fire Bob Iger. He thought Bob was stupid, or so he said. I thought he was being rash and said so: “Bob Iger knows ABC cold.” I later spent three hours over dinner with Iger — who’d heard of Eisner’s dissatisfaction — persuading him not to leave. I told him Eisner had a short attention span, and would soon be on to someone else. That was true: he promptly told me to fire Dennis Hightower, our head of television. Dennis was our only high-ranking African American executive, and I told Michael, “That’s a terrible idea for me or you.” Hightower stayed.

In 2005, after Eisner resigned under pressure and Iger replaced him, I finally grasped the method behind Eisner’s madness: he saw Iger as a future successor. Bob has led Disney to new heights as CEO. He built the business with high-wire acquisitions and a stronger foreign profile, more or less what I’d tried a decade earlier. He made big M&A bets on Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, and Fox, and built the Shanghai Disney Resort. Bob was smart about it. First he changed the culture, dismantling the strategic planning group and erasing Eisner’s imprint. And then he empowered the people around him, as any successful leader must.

I still think I could have run a big public company, given time to learn and adjust. But I never could have run that company as Eisner’s number two. Disney’s culture under Michael was too ingrained and ingrown. I lacked the power to change it or the temperament to blend in. Bert Fields later told me that Eisner didn’t want me at Disney so much as he wanted me out of CAA, in order to weaken the agency’s power — all agencies’ power. I’d been a thorn in Disney’s side for too long, so he pulled it out. Humiliating me every day was just a bonus.

“The bad publicity came, and it was pretty bad.”

— Michael Ovitz

Right after I got fired, Teddy Forstmann called and said, “I want you to go on the board of Gulfstream,” an aerospace company his equity firm owned. “It’ll help you.” “Thanks,” I said, touched by his loyalty. “But I can’t. It won’t be good for Gulfstream — I’ll be getting a lot of bad publicity.”

“You’re on the board,” he said, and hung up.

The bad publicity came, and it was pretty bad. Headlines everywhere, stories of my fall. Within days of my departure, a group of Disney shareholders brought suit against the company and me. They charged that I’d broken my contract and that my $130 million, no-fault payout was a fiduciary breach. In 2004, as the action headed toward trial in Delaware’s Court of Chancery, I seized it as a chance for vindication. I was raring to go, to tell the world what had really happened.

The judge, Chancellor William B. Chandler III, was sharp and attentive. And after he listened to thirty-seven days of testimony, his 175-page decision was strongly in my favor. Chandler found that I was “a poor fit with [my] fellow executives” at Disney, but he rejected the plaintiffs’ claim that I’d been untruthful or derelict in my duties. In approving my contract with the company, he observed, Disney’s directors were well aware I needed “downside protection” before taking the job. I was walking away from up to $200 million in booked CAA commissions. My severance would offset my losses if I were fired without cause — which I was.

While Chandler cleared the board of impropriety, he had harsh words for their conduct. Disney’s directors “fell significantly short of the best practices of ideal corporate governance,” he wrote. He called Eisner a “Machiavellian” CEO who stacked his board with cronies and “enthroned himself as the omnipotent and infallible monarch of his personal Magic Kingdom.”

That’s the tragedy that can befall the company man: we come to believe we are the company.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.