A little-noticed zoning twist is set to spark a home-building boom in L.A.

- Share via

On a recent spring day, bulldozers leveled the low-slung Holiday Auto Plaza in Palms, home to several repair shops. Just another unremarkable commercial building being swept away — except for the intriguing turn that its replacement might mark for L.A.’s housing crisis.

The Venice Boulevard site is currently zoned for 46 residential units. But because the plot is near a major bus stop, its developer can now plan much bigger: an eight-story building with 79 units, eight of them reserved for extremely low-income households.

A half-mile away on Overland Avenue, another developer is leveling an auto repair shop and 17 existing homes on land zoned for 110 units. He’s building 168 market-rate homes and 19 extremely low-income units. Walk across the street and down two blocks, there’s another similar project.

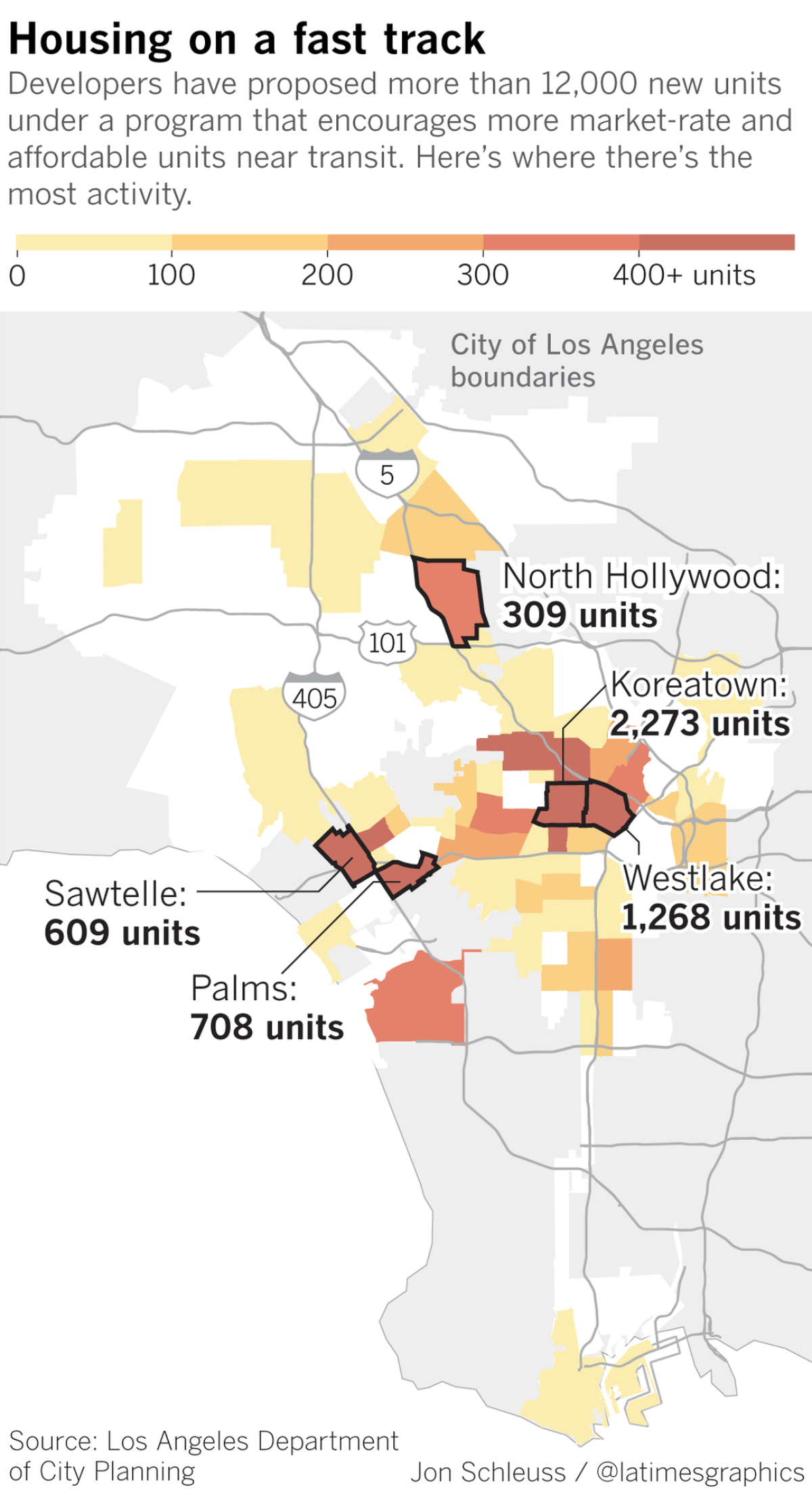

Across Los Angeles, developers are flooding the city with such proposals, taking advantage of a new city program that allows for larger projects near transit if developers keep some units affordable for people with lower incomes.

Since the Transit Oriented Communities, or TOC, program launched in September 2017, developers have proposed more than 12,000 units, including at least 2,300 homes kept affordable for lower-income households, according to city data through the end of 2018.

“It’s busy,” said Laurie Lustig-Bower, a commercial real estate broker with CBRE. “A significant amount of my business” has been these density-boosting projects.

Given the newness of the program, most of the resulting projects haven’t broken ground and none have yet opened, according to the city. And the number of new units pales in comparison with the 500,000 additional below-market homes Los Angeles County needs, according to the California Housing Partnership.

But affordable housing advocates praise the program for making a dent and reserving many of the coming below-market homes for the very poorest. And as projects rise, Los Angeles is making further progress toward its goal of putting housing in central locations near bus and rail lines.

“The two biggest problems we have is our housing crisis and our traffic woes,” Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said in an interview. “TOC is an incredible weapon to help us address both.”

Protecting the displaced

Not everyone is a fan. Some homeowner groups criticize the streamlined process for increased-density projects. And some low-income advocates, though supportive in general, have raised concerns that to build new projects some developers are demolishing older rent-controlled buildings that can be a haven of lower-cost housing.

Garcetti’s office said that although more study is needed to determine the path forward, the mayor supports establishing a right of return for tenants, particularly those with low incomes, when rent-controlled or income-restricted homes make way for new projects, regardless of whether they’re TOC.

“We need to ensure the lives of the people who are being displaced are not sacrificed and traded for affordable housing for other tenants in need,” said Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival. “These people’s lives are going to be thrown into a tailspin.”

Under TOC, developers are allowed to build with fewer parking spots and can increase housing units by 35% to 80%, depending on how close a project is to a major transit stop. As the number of allowed units rises, so does the requirement for some to have below-market rents or mortgages. Developers can receive additional breaks on things such as project height and how close they can build to the property line.

No public hearings are required, and the city has little discretion to deny a project if it follows TOC guidelines.

“It’s created a more predictable process,” said Jessica Lall, chief executive of the Central City Assn., a downtown business group. She credited the planning department with going “bold” in crafting the program. “It’s delivered units faster, at a time we are facing a huge housing shortage.”

The zoning relaxation grew out of Measure JJJ, a 2016 ballot proposal that labor and low-income advocates said would create more affordable housing — and well-paying home-building jobs.

Most of the debate leading up to the vote focused on ballot language that required developers to pay union-level wages and build some below-market units if they received zoning changes or general-plan amendments. As opponents predicted, requests for those changes dropped sharply.

But the measure also instructed the planning department to craft a program to boost affordable housing within one-half mile of major transit stops. It was to be modeled after an existing state law that lets developers build up to 35% more units regardless of proximity to transit. Beyond setting that minimum density bonus, it left many of the specifics to the department.

The idea was to use the zoning code to make it profitable for companies to provide low-cost homes without public funding, which has been on the decline.

Beyond an increase in density, developers say TOC is profitable for them because, unlike zone changes and general plan amendments, JJJ kept union-level wages optional. Instead, it instructed the planning department to provide additional incentives if developers compensated workers at that level and, according to the planning department, only one TOC developer has taken advantage of those incentives.

It’s impossible to know whether construction would be greater if JJJ failed and TOC never was created, in part because developers, trying to get ahead of the restrictions on zoning changes and amendments, flooded the city with proposals before the vote.

The city’s lack of historical data tracking also makes it difficult to judge TOC’s full effect. But the bottom line for now is TOC last year helped lead to more market-rate and affordable units proposed through the planning department than in 2017 — and developers are setting aside homes for the poorest Angelenos in a way they weren’t before.

A rise in low-income proposals

City data show the largest category of affordable-housing proposals — at least 947 homes — is for extremely low-income households, or those with incomes of $20,350 or less for an individual or $29,050 for a family of four. Prior to JJJ, that’s a category the city didn’t even incentivize through zoning.

“It becomes an important homeless prevention strategy,” said Laura Raymond, director of the Alliance for Community Transit-Los Angeles, a coalition of low-income community groups behind JJJ.

The city has also partnered with the nonprofit People Assisting the Homeless, known as PATH, so it can contact developers and encourage them to rent below-market units to people already on the streets.

Local political officials cited the flood of projects as one reason to oppose the controversial Senate Bill 50, which failed earlier this month. That bill would have allowed four units on land now zoned for only single-family homes, and in some cases much larger projects.

TOC, on the other hand, can be used only on land where at least five units are currently allowed. Qualifying developments are scattered throughout Los Angeles. But the neighborhoods with the most units proposed are Koreatown, Westlake, Palms and Sawtelle — all areas with access to light rail or the subway.

Ken Kahan, president of California Landmark Group, is building on the Venice Boulevard site where an auto repair building previously stood. He said the reason for using TOC is simple: more money. In one instance, he even rejiggered a project already under construction in Sawtelle to add more units.

“If TOC was not economically more profitable, developers would not do it,” Kahan said. “The city has come up with a procedure to provide more housing — and more affordable housing without using city coffers.”

Some of the popularity of TOC projects probably is from developers who shifted already-planned projects from one program category to another. But TOC last year did help boost the total number of units proposed that need sign-off by the planning department.

In 2018, the number of market-rate units proposed through any sort of entitlement application rose 20% from 2017, when TOC largely did not exist, while the number of below-market units increased 2%.

Those increases may understate the scale of TOC’s effect on overall proposals; the data don’t include TOC projects that only asked for density and parking breaks and didn’t need planning approval.

A crisis of affordability

The lack of affordable housing in Los Angeles, and elsewhere across the state, has grown into a full-blown crisis. More than half of California tenants pay rent that experts deem unaffordable. Home prices, meanwhile, have surged 80% since 2012, according to Zillow.

Economists generally agree the root cause for both is that for decades too few homes were built relative to population and job growth. Opposition from existing residents is cited as a major factor.

Research indicates that any increase in supply helps hold down costs on a regional level, while UC Berkeley researchers found below-market homes are most effective at limiting displacement of low-income families. Some building proponents argue that even adding a luxury development helps bring down costs in a neighborhood, because well-off households will move there and free up older units.

Not everyone agrees that’s the case. The L.A. Tenants Union, which opposed JJJ, worries that the increase in mostly market-rate apartments will convince nearby landlords that they, too, can charge top dollar.

Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal, a co-founder of the L.A. Tenants Union, called TOC a “scam” for allowing the demolition of old rent-controlled apartments in exchange for income-restricted units that revert to market rents in 55 years. She said what’s needed is political will for an investment in public housing, rather than “tinkering around the edges.”

The housing department says that all rent-controlled units leveled for TOC projects must at a minimum be replaced with the same number of income-restricted affordable units or homes subject to rent control. In some cases, all the non-income-restricted units would be rent controlled, which means landlords set initial rent but then face limits on annual increases for as long as a tenant stays.

Through 2018 developers have filed TOC applications with the planning department to build 19 new units for every demolished unit, rent controlled or not. The ratio for below-market units is 3.4 new homes for every unit lost.

Gross called those ratios positive. But he said developers should do more than just give displaced rent-controlled tenants the relocation assistance they are entitled to. That money can evaporate quickly, particularly when longtime residents are suddenly forced into today’s high-cost rental market. “There needs to be a commitment to ease and mitigate the impact better,” Gross said. “You are pushing people out onto the streets to build housing for people already on the streets.”

Some residents are up in arms for other reasons.

On Tuesday evening, about 80 people packed the auditorium at Toluca Lake Elementary School for a contentious meeting. Representatives of a developer had agreed to present plans for a four-story, 38-unit TOC project with ground-floor retail and four of the units reserved for extremely low-income households.

Most of those in attendance appeared to be opposed. They spoke of a lack of parking and the loss of a village-like atmosphere and their post office, which would be demolished. One man called the design “pedestrian.” A woman said the project would “alter the character of the neighborhood and the village beyond recognition.” The crowd clapped in response.

Gary Benjamin, a consultant for the project, said the reduced on-site parking would be supplemented by an adjacent surface parking lot the developer owns. And he said the developer tried to make the project fit the village, in part by reducing the height of the roof in places.

Benjamin said the developer isn’t opposed to making some “reasonable” changes to respond to feedback. But he also noted that a goal of TOC was to shield projects from endless debate as long as they follow specific guidelines.

“As long as you comply … the property should just be approved,” he said. “We need the affordable units and we need housing supply.”

Times staff writer Jon Schleuss contributed to this report.

Follow me @khouriandrew on Twitter

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.