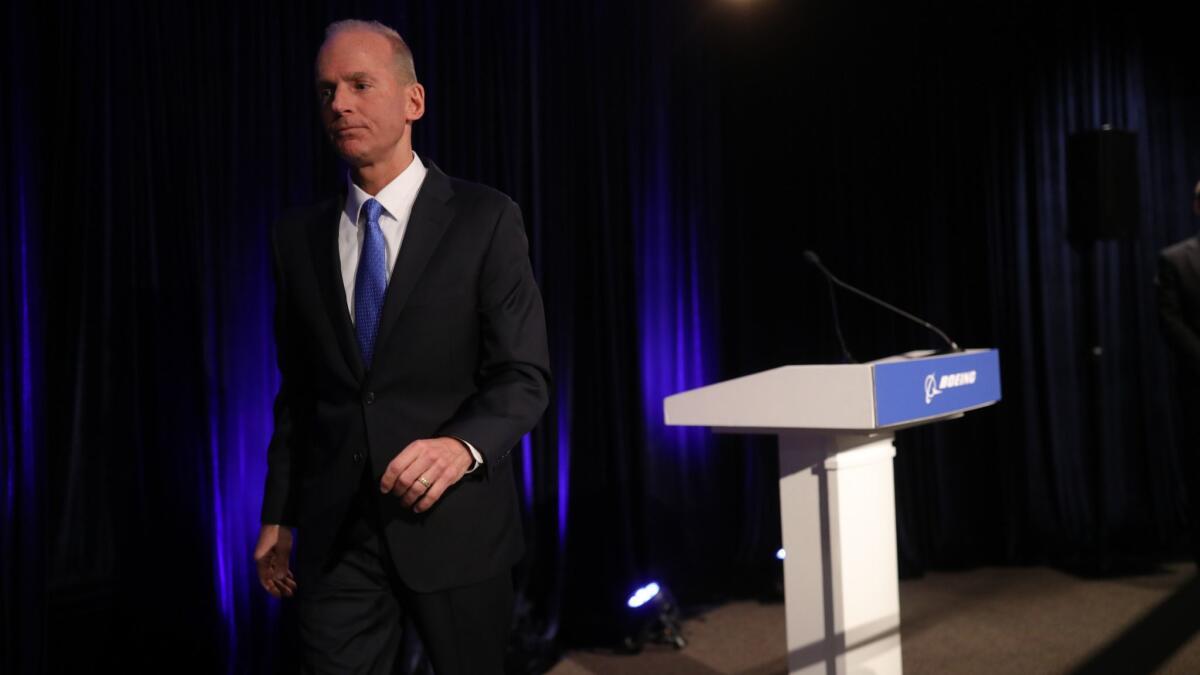

Can Boeing CEO Muilenburg engineer a recovery course amid 737 Max crisis?

- Share via

Dennis Muilenburg wanted to be “the world’s best airplane designer,” he once told a reporter. Growing up milking cows on his father’s farm in Sioux County, Iowa, he earned a coveted place studying aerospace engineering at Iowa State University, where a scholarship named after a former Boeing chief executive won him an internship with the world’s largest passenger aircraft manufacturer.

That launched a 34-year, one-company career and led to Muilenburg’s appointment as chief executive in 2015. But now he stands accused of helping precipitate the biggest crisis in Boeing’s 103-year history and of a faltering response that may deepen the company’s troubles.

Questions over whether design and software flaws caused the fatal crashes of two of Boeing’s top-selling passenger jets have handed the man in its cockpit a career-threatening challenge.

It was still dark outside on the Sunday in March when Muilenburg was woken by news that Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 had gone down, killing all 157 people aboard. It was the second such disaster in five months, and, like the Indonesian Lion Air plane that plummeted into the Java Sea last October at the cost of 189 lives, the model was a 737 Max 8, the single-aisle passenger aircraft at the heart of Boeing’s short-haul product line.

Within three days, regulators began to suspect that the same flight control system had played a role in both disasters and authorities from Beijing to Washington grounded all the nearly 400 Max aircraft Boeing had delivered.

The fallout could cost the company billions of dollars. Shareholders and families of the dead have brought lawsuits, airlines will claim compensation for the costs of the grounding and at least one of the government investigations it faces could end in prosecutions.

The crisis demands that Muilenburg, 55, summon the kind of political skills they do not teach aviation engineers. He has to address accusations that engineering mistakes or deliberate shortcuts led to 346 deaths. He also has to restore the trust of regulators, airlines and pilots — as well as navigate a U.S. president with strong views on aviation.

Muilenburg must defend the world’s largest commercial aircraft manufacturer against charges that it rushed a plane to market without paying enough attention to how design changes would affect its safety — or even that it deliberately ignored the risks. He will also have to answer charges leveled by some pilots, aviation experts and politicians that Boeing could have prevented both crashes by training pilots on the Max’s new anti-stall maneuvering characteristics augmentation system (MCAS) and that after the first crash it resisted rushing out a software update that pilots from American Airlines called for.

Some of these accusations relate to decisions that predate his tenure at the helm, but others were taken squarely on his watch.

Most of all, he will need to convince a skeptical public that the aircraft — which Boeing hopes will be back in operation in August — is safe to fly.

Boeing says it has completed a software update that solves the Max’s MCAS problem but the Federal Aviation Administration is not satisfied yet. Global aviation regulators met last week to draw up a plan for recertifying the aircraft as safe.

What happens next — especially in Washington, where Boeing faces congressional and federal investigations and a criminal probe — could put question marks over some of Boeing’s nearly 5,000 orders for the Max, and over Muilenburg’s position.

His response so far has highlighted his strengths but exposed some serious blind spots, according to industry veterans. But with regulators and politicians increasingly in control of the next phase, he faces new tests.

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a professor at the Yale School of Management, says that in the league of leaders’ handling of crises, from Takata’s exploding air bags to General Motors’ faulty ignition switches, “I give [Muilenburg] a B.” He argues, however, that the chief executive’s “engineer’s personality” has not helped.

Dave Calhoun, Boeing’s senior independent director, says Muilenburg deserves credit for his internal communications but what he can say in public has been constrained by regulators. “He has a very difficult time when [he’s not allowed to rebut] all of the speculative comments that are thrown at him in interviews,” the Boeing director says, “and when he does it looks defensive.”

Asked to explain Muilenburg’s handling of the seven months since the Lion Air crash, analysts and colleagues tend to start with the observation that he is, first and foremost, an engineer.

His background and hands-on style have helped in recent weeks as he has toured plants, hosted customers and accompanied pilots on flights to affirm the safety of the Max, Calhoun says.

Muilenburg arrived in the top job with a reputation as a cost-conscious defense executive. In his mid-30s he had led the weapons design component of a bid for the $200-billion U.S. Air Force Joint Strike Fighter contract. Boeing lost that bid, but Muilenburg rose rapidly and was running the whole defense division by the age of 45.

When Muilenburg succeeded Jim McNerney in 2015, Boeing was mired in accounting investigations into its delayed 787 Dreamliner long-haul program and falling behind Airbus in the short-haul passenger market. Under pressure to compete with its European rival, Boeing opted to tweak the 737 — which had been flying since the 1960s — rather than start from scratch.

It did not take long for the competitive environment to change in Boeing’s favor, and by last summer, the punchy confidence Muilenburg brought to the company was on display at the U.K.’s Farnborough Air Show.

That self-assurance has been missing during what Muilenburg has called “the most heart-wrenching” weeks of his career.

Since 1982, when Johnson & Johnson recalled 31 million bottles of Tylenol after some painkillers were laced with cyanide, there has been a playbook for corporate crises: take swift, decisive action and put the boss in front of the TV cameras to explain and reassure. Muilenburg has not followed this model.

“There is a consensus that he was slow [to respond],” says John Chevedden, an activist Boeing shareholder.

Not only did Muilenburg insist the Max could keep flying after Chinese, U.K. and European regulators had grounded it, he was also all but invisible to the flying public.

The company only put its leader in front of journalists seven weeks after the Ethiopian Airlines crash. The usually affable Muilenburg appeared stiff and defensive during a 16-minute press conference, taking just a few questions before bolting for the door after being asked whether he should resign.

But he had also adopted a more combative stance, suggesting that pilot error and other factors should share blame for the crashes. Critics say Boeing rushed the Max through certification without revealing that the MCAS system had tremendous power to force the nose of the aircraft down in certain circumstances. Boeing denies this claim.

Even if flaws in MCAS were just one link in “a chain of events,” as Muilenburg now suggests, that would not absolve Boeing, says Scott Hamilton, an analyst at Leeham News and Analysis, an aviation website. “Even if the pilots committed by-the-book errors I would argue that they were trapped into making the errors by MCAS and by not knowing about it. They were trapped into making them by Boeing.”

In a further blow to its credibility, Boeing said over the weekend that it had corrected a flaw in the software of Max flight training simulators because they did not accurately reproduce the conditions in the Ethiopian flight.

“Boeing has been doing a lot of half measures,” says Jim Corridore, an aerospace analyst at CFRA Research. “I was applauding them when they said, ‘We own this,’ but then they backtracked.”

The reason, he and other analysts surmise, is fear of legal liability. “There are many good reasons not to have lawyers run a company,” says Richard Aboulafia at aerospace consultancy Teal Group. “It’s the wrong gamble: The upfront pain from litigation can be managed. Reputational and product image damage, that keeps on giving.”

Could the 737 Max disaster force Muilenburg out?

For now, he has the advantage of a supportive board, which paid Muilenburg $23 million last year and whose lead independent director defends him in glowing terms: “So far he has passed all the tests.... He is early in his career but this will be a defining moment in his leadership and I think it’s going to serve him incredibly well,” Calhoun says.

April’s annual meeting rejected a proposal to split his dual roles and pick an independent chair, Corridore says, though support for doing so rose to 34% from 25% the year before.

For Aboulafia, Muilenburg’s fate is tied to Boeing’s share price, which has held up “remarkably well.” It is 20% off its February peak, but over 12 months Boeing stock has only slightly underperformed the S&P 500 index, despite the Max crisis and the U.S.-China trade battle. Boeing is heavily dependent on orders from Chinese airlines.

At $358.75 at the close Tuesday, the shares remain far above the $146.47 price on the day Muilenburg was named CEO. His commitment to share buybacks and dividend increases has helped but so has the strong increases in Boeing’s top line and profit margins.

But outside the investment community, Muilenburg faces a much tougher ride. Consumer activist Ralph Nader, whose grandniece died in the Ethiopian crash, says Boeing put shareholders before safety. Muilenburg should resign, he believes. “If he pinched a secretary on the rear he would have been forced to resign; instead he pursued a policy of overriding their own engineers, overriding objections from pilots, and killed 346 people,” Nader says.

Aboulafia agrees that Boeing “obsessed over” its share price and undervalued engineers during the years of Max development. “Customers came second. Company assets, such as people, became a commodity, something to be measured against returns.”

Boeing denies having cut corners on safety in designing the Max, but these questions will be a focus of the lawsuits and investigations it faces. Muilenburg is likely to find himself testifying before Congress.

Perhaps the biggest imponderable is whether the public will shun the Max once it returns to the skies, probably starting in the U.S. in August. A Barclays survey of 1,700 passengers found 44% said they would wait a year or more before flying in a Max.

Yet industry veterans doubt this prediction, saying passengers’ concerns over aircraft safety typically fade fast. A Reuters/Ipsos poll released last week found most U.S. air travelers said ticket prices were more important to them in choosing flights and only 43% even knew which model had been involved in the recent crashes.

© The Financial Times Ltd. 2019. All Rights Reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.