CES 2014: Consumer electronics show to feature ‘Internet of things’

- Share via

To glimpse the future of consumer electronics, get a grip on the world’s first Internet-connected tennis racket.

With tiny sensors embedded in the handle, the racket measures a player’s strokes, topspin and just about everything else that happens when the ball is struck.

All that information is instantly relayed via a wireless Bluetooth connection to a smartphone app. The player can later view and analyze it on the Web.

“It’s going to be a huge change for the tennis player,” said Thomas Otton, director of communications for Babolat, the French tennis company that invented the original cow-gut racket strings 140 years ago. “They are going to have access to all kinds of information and data that will help them progress much faster and have more fun. It’s a true revolution.”

The $399 Babolat Play Pure Drive tennis racket is one of many devices that are expected to be rolled out in the next several years and make up the so-called Internet of things, tech industry jargon for just about any object that is connected to and in some cases run over the Web.

By 2050, analysts project, there will be 50 billion Internet-connected devices, or five gadgets for every man, woman and child.

“It transforms things in pretty significant ways,” said Scott McGregor, president and chief executive of Broadcom, an Irvine company that hopes its semiconductors will power this trend. “You’re going to see an explosion of devices.”

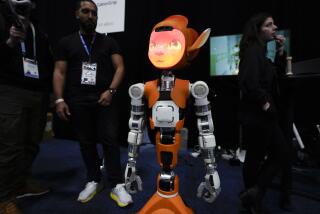

No wonder, then, that Internet of things will be a major theme at International CES, the huge consumer electronics show that begins in Las Vegas this week.

More than 150,000 people are expected to descend on Las Vegas as CES begins its weeklong invasion, which remains one of the tech industry’s largest gatherings. There will be two days of media previews starting Sunday before the show officially begins for industry attendees Tuesday.

This year, CES will feature keynote speeches from Yahoo Chief Executive Marissa Mayer, Cisco Systems chief John Chambers and Sony chief Kazuo Hirai. Later in the week, attendees can catch luminaries such as Twitter chief Dick Costolo and Qualcomm Chairman Paul Jacobs on stage.

The show’s record 1.861 million square feet of exhibit space represents an endurance test for even the hardiest of tech warriors. Those able to meet the challenge will see the usual array of new laptops, tablets and smartphones.

But these are increasingly dwarfed in prominence by special exhibits for connected automobiles, the smart home and wearable computers, the latter with an emphasis on fitness and health products. These three categories are mere slices of the much broader trend toward the Internet of things that is gradually turning the entire physical world into a vast connected network of objects.

Thanks to smaller, cheaper sensors, speedier wireless connections and the explosion of smartphones and tablets, it’s becoming easier and more cost-effective to link just about any object to the Internet.

Gadget by gadget, people are coming to expect that even the most common things will be more useful when they are connected. Pets. Livestock. Sports equipment. Watches. Power meters. Light bulbs. Washing machines. Thermostats. If you can think of it, someone has probably stuck a sensor on it and connected it to the Internet.

“I think a lot of this is going to start with the smart home,” said Kelly Davis-Felner, a representative of the Wi-Fi Alliance, whose members have played a key role in enabling this connected world. “The smart home is going to be built brick by brick until 10 years from now we’re going to be looking back and saying, ‘Wow, I can’t believe there used to be a time when everything wasn’t connected.’”

This type of connectivity is already widely embraced by businesses, which use sensors to wirelessly track supplies, packages and the performance of machinery. But big drops in the cost of computer memory and sensors, coupled with dramatic improvements in battery life, are pushing the spread of connected devices to consumers.

“We’re seeing an acceleration of uses with the consumer Internet of things,” said Patrick Moorhead, principal analyst for Moor Insights & Strategy. “You could have done many of these things before. But the battery life might have been one hour. Now it lasts a week.”

Thanks to the mobile computing revolution, these connected devices don’t need big computer screens and buttons to be useful. And they never need to be plugged into a desktop computer to be synced. Smartphones and tablets increasingly serve as the dashboards to control them.

For instance, a Fitbit wristband that tracks the user’s physical activity and calorie intake needs only a tiny LED screen. The information is beamed to a smartphone app, where it can be stored, processed and tracked.

“On many of these devices, sensors pull off the unique information and feed them to your smartphone,” said Shawn DuBravac, chief economist and director of research for the Consumer Electronics Assn., the trade group that runs CES. “These devices don’t need to be computers by themselves.”

There is no single killer app driving this adoption. Many of the devices have only a single purpose or function, which, given their low cost, seems to be fine with consumers.

Connectivity has also become laden with tremendous hype created by a consumer electronics industry that needs to continuously find new gadgets to sell. Many of the industry mainstays, such as televisions, PCs and even smartphones and tablets, are seeing their growth slow or sales decline as it becomes harder to produce breakthroughs that inspire people to replace older devices.

As a whole, connected gadgets are being marketed as devices that will help consumers lead healthier, happier and safer lives. Smart homes will use less energy. Connected cars will prevent accidents and be more fuel efficient. Wearable computers will help users stay fit and improve their moods, proponents say.

Of course, the drive to connect everything creates a new set of problems. The Internet of things is collecting and storing ever larger amounts of personal information about users. And a number of analysts have pointed out that many of these new gadgets lack even the most elementary protections against hackers.

And on a more practical level, as the number of connected devices in people’s lives proliferates, managing them will become increasingly taxing. Analysts point out that if the industry wants to keep the revolution going, it will have to continue defining technology standards that make it easier for all these devices to communicate with one another seamlessly and eventually work together with no human interaction.

“We’re entering the age of autonomy,” DuBravac said. “We’ll need these machines to make sense of all this information floating around us and make adjustments for us, whether it’s just turning the lights on when we wake up or a cutting board that tells us how to adjust our caloric intake. It’s too much information for people to manage on their own.”

Twitter: @obrien

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.