‘Coronado High’ author blazes a trail for journalists in Hollywood

- Share via

Last year’s “Argo” landed producers George Clooney and Grant Heslov the Oscar for best picture, cemented Ben Affleck’s reputation as an A-list director and filled distributor Warner Bros.’ coffers with proceeds from a $232-million worldwide gross.

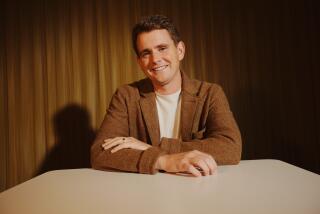

The movie also had a major effect on Joshuah Bearman, the Echo Park-based journalist whose 2007 Wired magazine story was the basis for the film.

It led him to think about storytelling in a different way — and to go entrepreneurial with his latest project, a tale of San Diego drug smugglers.

PHOTOS: Hollywood backlot moments

Journalists have long had their published pieces bought by the movie studios. But even before Bearman completed “Coronado High,” a roughly 9,000-word piece about 1970s-era San Diego drug smugglers that appears in this month’s GQ magazine, he was finalizing a movie deal for the story with Sony Pictures Entertainment and Clooney’s production company.

An arrangement was also struck for GQ to delay publishing more than an excerpt of “Coronado High” on its website until August so the story could appear online first in even longer form with a different company — earning Bearman a trifecta revenue package.

On Thursday, a 25,000-word version of “Coronado High” was released by the Atavist, a digital publisher of long-form journalism. The Brooklyn, N.Y., company is selling the story as an e-book single and on its website, where it is augmented with audio and video elements.

“It’s thinking about a story being able to serve different purposes,” said the lanky, bearded Bearman, 41, nursing a beer on the patio of a Silver Lake restaurant. “I started seeing, once ‘Argo’ was optioned, how nonfiction and print narratives can be appealing to Hollywood and find a different or bigger audience — and, in the case of ‘Argo,’ an audience beyond my expectation.”

In an age of shrinking magazine budgets and a diminished market for long-form journalism, Bearman views his multifaceted approach to disseminating “Coronado High” as a way to tell the sort of lengthy, narrative-driven story he’s drawn to in a way that few publications attempt these days, while also seeking a wider audience.

VIDEO: Affleck and Clooney talk making ‘Argo’

“It’s a way most nonfiction writers don’t think, because they are focused on the print story,” said Bearman, a contemplative interviewee prone to pauses before diving into lengthy responses to questions.

Bearman’s Hollywood efforts don’t involve GQ’s parent company, Conde Nast, which is making a showbiz push of its own. The publishing giant’s entertainment division, Conde Nast Entertainment, formed in October 2011, is developing films and other projects based on stories that appear in the company’s publications.

Kit Rachlis, editor of the American Prospect and former editor of Los Angeles Magazine, said Bearman is on to something new. But he isn’t sure that most journalists could follow Bearman’s model without an “Argo” behind them.

“Not a lot of writers have that clout,” Rachlis said. “But the fact that a writer is doing that for himself and taking control is terrific.”

The “Coronado High” story was brought to Bearman’s attention by David Klawans, an independent film producer who scours the Internet in search of great stories that could be developed into films. Klawans, who like Bearman is represented by United Talent Agency, similarly unearthed the story that would become “Argo.”

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

The Coronado tale had received coverage in the 1970s and ‘80s, and when Klawans discovered it in the mid-1990s, he was intrigued by the possibilities.

“I always felt … the craziness of the story could one day make a great feature,” said Klawans, who in 1995 pitched the story to filmmaker Oliver Stone (he passed on it).

Bearman said that during the six months he spent reporting the Coronado story, sifting through court documents and conducting in-depth interviews, the project blossomed: “It turned into a coming-of-age story, which made it into a much bigger story than I expected.”

Getting “Coronado” published on multiple platforms wasn’t without complications. In order to secure the arrangement, the Atavist, which published Bearman’s “Baghdad Country Club” in December 2011, required a period of digital exclusivity for the full story — a deal the company worked out with GQ.

Bearman said he was paid his standard fee by GQ but relinquished upfront compensation from the Atavist, which often pays writers $5,000. Bearman will, however, collect half the revenue generated by sales of the story — typical of a writer’s deal with the Atavist.

Unlike many writers who contribute to Conde Nast’s stable of publications, Bearman opted out of a contract from the company’s entertainment division that covers movie rights and is separate from its standard magazine deal. Bearman was able to forgo the film rights deal because Conde Nast Entertainment offers an exemption to writers who have previously produced or optioned a movie or TV project.

ON LOCATION: Where the cameras roll

The film rights deals offered by Conde Nast Entertainment guarantee writers an upfront option fee of up to roughly $5,000, with the potential for them to receive more than $150,000 or 1% of the value of the sale to a movie company.

But the Sony deal, which is nearly complete, could net Bearman a bigger payday. Literary agent Joel Gotler of Intellectual Property Group said that by his conservative estimation a writer with Bearman’s credentials could receive a $150,000 option fee from a studio, with the prospect of a “seven-figure” payday if the project moves forward.

“If you are the guy who wrote the story that became ‘Argo,’ it’s going to be a big number,” said Gotler, who does not represent Bearman.

Conde Nast declined to address its film rights contracts, but a source close to the company characterized the deals it has struck with writers as fair market rate. The source requested anonymity because the contracts are confidential.

Dawn Ostroff, president of Conde Nast Entertainment, said she expects to see “a collaborative convergence expanding between the creative community and the business side” of the publishing company.

“Film and television studios historically own the underlying rights of their properties, while magazine publishing has not,” said Ostroff, whose group has more than 50 projects in development. “That needs to change, so when we make the investments in content, we need to begin benefiting from the potential returns.”

Finishing his beer, Bearman made it clear that, despite his new business model and the executive producer credit he would get on the Coronado film, he’s no budding mogul.

“I like being able to do the nonfiction narrative piece … and then have that story go off and be turned into something I would never be able to do,” he said. “I wouldn’t make ‘Argo’ on my own.”

MORE

PHOTOS: Highest-paid media executives of 2012

ON LOCATION: People and places behind what’s onscreen

PHOTOS: Hollywood back lot moments

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.