As businesses rush to exploit GOP tax cuts, government revenue may shrink more than expected

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — As soon as the last major tax overhaul was enacted in the fall of 1986, accountant Edward Mendlowitz remembers working around the clock to convert corporations into partnerships and other so-called pass-through businesses to take advantage of the new tax code.

Now with congressional Republicans drawing closer to passing a package of $1.5 trillion in net tax cuts, mostly for corporations, Mendlowitz reckons he may soon be doing the reverse. The corporate tax rate is expected to fall from 35% to about 20%, its lowest in more than 75 years and considerably less than what pass-through taxpayers are likely to face.

“We’re not taking the pencil and paper out yet, but at some point we’re probably going to switch a lot of them,” said Mendlowitz, a partner with WithumSmith+Brown in New Brunswick, N.J.

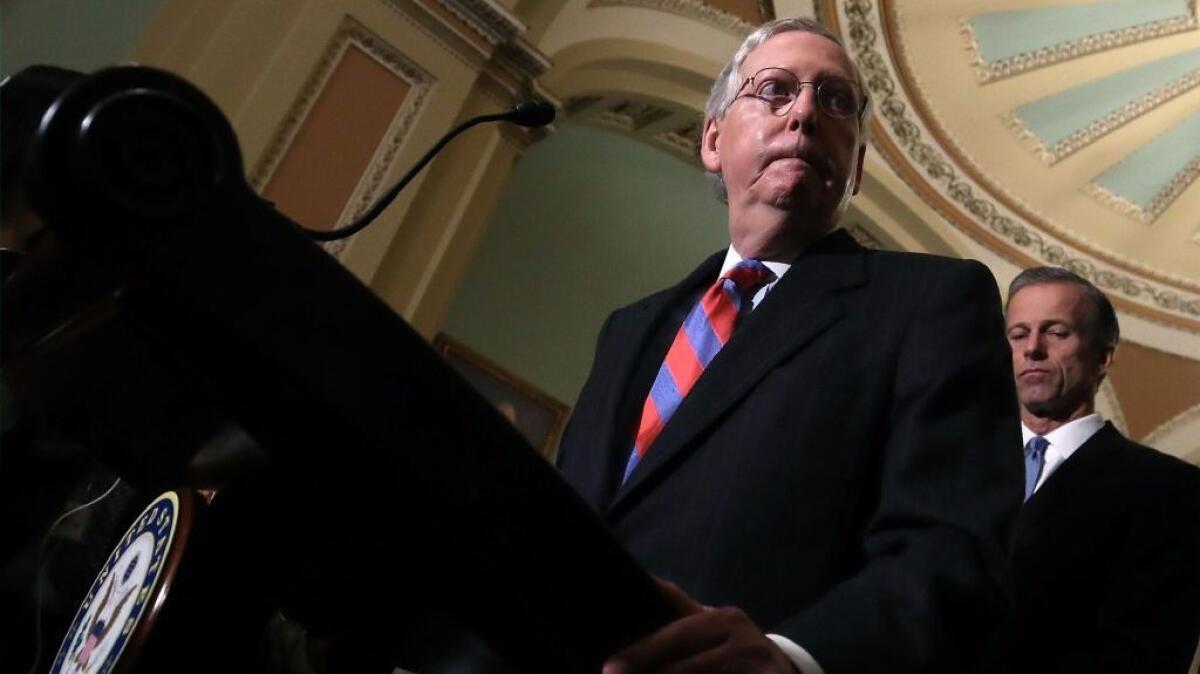

The specter of mass conversions — and the potentially huge tax revenue losses resulting from them — is but one vexing problem for GOP leaders as they try to stay within debt limits and resolve differences in the way the Senate and House bills would treat pass-through entities, which account for about 95% of all businesses.

In the view of tax experts, the two Republican versions on taxing pass-throughs are far apart. Where the two chambers come down on the matter could have implications not only for the federal debt, but the level of entrepreneurial activity and even employer-employee relationships, not to mention whether GOP leaders ultimately succeed in passing a final tax legislation.

Analysts also see the pass-through provisions as particularly susceptible to workarounds and manipulation. Despite anti-abuse rules that are included in the bills, the haste and unconventional manner in which GOP leaders are trying to push through their tax plan adds to the risk of leaving loopholes that clever lawyers and accountants will almost certainly be able to exploit.

For example, the proposed Senate changes could spur some salaried employees to make an arrangement with their employers to form their own companies to take advantage of the pass-through deductions not allowed for individual taxpayers. That could further increase the already growing trend of consultants and independent contractors.

“Say you’ve got two businesses in the same industry,” said Howard Wagner, managing director at Crowe Horwath LLP, a public accounting firm. “One business model is to hire employees, the other is to use independent contractors. Will the one who is able to use independent contractors be able to attract better talent if the lower rate is available to those individuals?”

Wagner added: “These things have real-world consequences.”

The bills now in conference in the Senate and the House, both under GOP control, share key provisions. They are fundamentally aimed at making big corporate tax cuts permanent and shifting to a territorial system in which only domestically generated income would be taxed.

The Trump administration and Republican backers in Congress argue the cuts will ramp up investments, stimulate economic growth and lead to sizable wage gains for the average American.

Congressional Democrats and many economists doubt the tax savings to already cash-rich corporations and individuals will trickle down to middle-class households, and they worry that the massive tax cuts will further swell the nation’s public debt, triggering higher interest rates that could neutralize potential economic gains from a tax overhaul.

The House tax bill passed in mid-November, the Senate’s in the wee hours Dec. 2 by a narrow 51-49 vote. There are important clear-cut differences, notably over whether to repeal the individual mandate in Obamacare and how to handle the alternative minimum tax.

But the pass-through provisions may be the most complicated and fraught with uncertainties in terms of how they will play out and the potential cost to Uncle Sam.

Pass-through entities are so named because their incomes, for federal tax purposes, are treated as having “passed through” directly to the owners. Most pass-throughs are mom-and-pop operators, but they include large law firms and hedge funds that are structured as partnerships or what are known as S corporations, as opposed to C corporations like publicly traded Wal-Mart and Microsoft. Only C corporations are subject to the federal corporate income tax, now at 35%.

Pass-through owners are currently taxed at the same rates for individuals, with the top tax bracket at 39.6%

The GOP Senate tax plan would slightly lower the maximum individual tax rate to 38.5%, and would provide a special 23% deduction on qualifying pass-through income. For pass-through owners in the highest tax bracket, that means their effective tax rate would be a little less than 30%.

The House measure takes a different approach. It keeps the 39.6% marginal tax rate for individuals, but sets a new top rate of 25% for pass-throughs. Owners of professional services such as legal and consulting businesses would not qualify — although real estate investment firms like those controlled by President Trump would — whereas the Senate version allows those and many other service providers to take the pass-through deduction from their incomes as long as they do not exceed $500,000 for couples.

The lower House rate for pass-throughs — 25% compared with the effective rate of 30% with the Senate bill — means it will be more expensive to go with the House plan. The cost of the pass-through tax cuts envisioned by the House is about $600 billion over 10 years, while the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates it at $340 billion for the Senate plan.

That is a big gap that will be hard to bridge, but it is further complicated by the fact that both GOP versions for treating pass-throughs could have major unintended but foreseeable consequences.

On the Senate side, even with the special 23% deduction, the effective tax rate for high-profit pass-throughs would be almost 10 percentage points higher than the 20% marginal rate for C corporations, and that does not include the deduction that corporations can take for state and local taxes. (Those deductions would be eliminated for taxpayers filing individual returns.)

That will give pass-through taxpayers a strong incentive to switch to C corporations. And Mendlowitz, the New Jersey accountant, says that would not be hard to do — it essentially involves filing a three-page form with the Internal Revenue Service and meeting certain conditions.

That many pass-throughs could convert to corporations has not been lost on the GOP leadership, which can ill-afford to lose any party member vote. Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.) has been championing greater pass-through benefits for a wider array of smaller businesses, but now worries that the package may open a floodgate of conversions that could result in far lower tax revenues than estimates show.

“That’s why I’m trying to convince my colleagues, ‘Let’s fix this,’” Johnson said this week, offering scenarios in which a wave of conversions could add hundreds of billions of dollars of losses to government coffers.

Yet congressional Republicans have practically no room to add to deficits beyond the $1.5 trillion allowed under congressional budget rules. Already they are under criticism from many economists and even some conservative circles because their tax plan is projected to boost the nation’s public debt by $1 trillion over the next decade, after accounting for the economic growth they are expected to spur.

Don Susswein, a principal at the accounting firm RSM, argues that the House version is the better of the two because it would do more for the economy by stimulating investments and entrepreneurial activity. Under the House bill, so-called passive pass-through owners — or investors — would get the lower 25% rate, but active owners involved in managing pass-through entities would see a smaller benefit depending on how much capital was invested.

In creating separate tax calculations for active and passive pass-through owners, the House bill is even more complicated than the Senate’s, undercutting a key aim of tax reform, to simplify an extremely complex tax code.

What’s more, the House tax provision for pass-throughs is seen as skewed more to wealthier individuals than the Senate one — and no less vulnerable to be gamed. As it stands now, the bill excludes certain investment-income items from getting the lower pass-through rate, such as capital gains and annuities — but not others.

“I think investors will try to channel more of their investment income, their rents, their royalties, through pass-throughs,” said Steven Rosenthal, a senior fellow at the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center. “That’s how the system will be gamed the most.”

Even as the Treasury and the IRS will surely write guard rails and anti-abuse rules, he said, past experience suggests that it will take many months if not years to catch up to taxpayers and all of the abuses and glitches that people will be exploiting.

“Meanwhile,” he added, “the Treasury loses a lot of money.”

Times staff writer Lisa Mascaro in Washington contributed to this report.

Twitter: @dleelatimes

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.