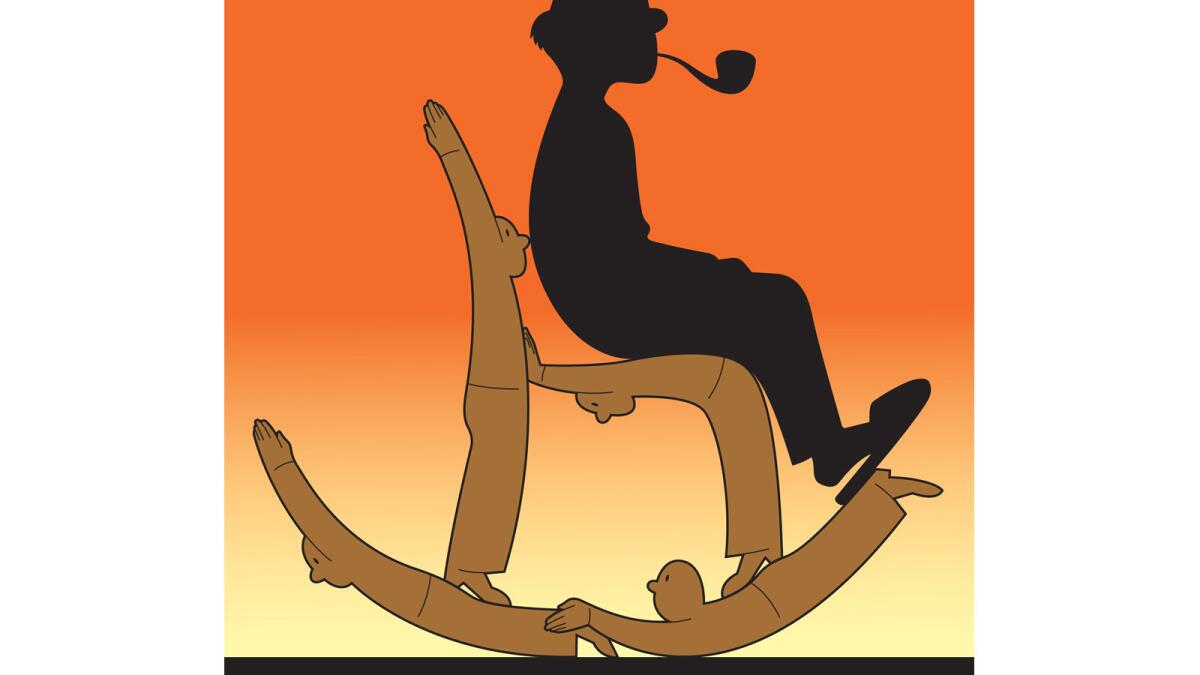

99 ways to boost pensions in California -- at public cost

- Share via

Directing traffic is part of a police officer’s job, and in the city of Fountain Valley, keeping cars moving comes with a $145 monthly bonus — and a bigger pension.

Fountain Valley officers can also pump up their pensions by working with police dogs or mentoring schoolchildren. Those who stay in shape get as much as $195 more each month.

All these perks boost officers’ salaries and add thousands of dollars to taxpayer-funded pensions for years to come.

The California Public Employees’ Retirement System made these higher pensions possible. The nation’s biggest public pension fund voted in August to adopt a list of 99 bonuses, ensuring that newly hired California public workers would receive the same pension sweeteners as veteran employees.

The long-term cost of pensions calculated with bonuses is billions of dollars more than with base pay only. But the exact price tag remains a mystery. The labor-dominated CalPERS board voted without estimating the potential tab.

The vote raised alarms on Wall Street, where analysts have warned about the skyrocketing costs. With $300 billion in investments, CalPERS estimates it still needs an additional $100 billion from taxpayers to deliver on its promised pensions to 1.7 million public workers and retirees. That amount would be enough to operate the 23-campus California State University system for 16 years.

Gov. Jerry Brown, who pushed through a 2012 law to stop workers from using questionable perks to unjustly inflate their retirement pay, wants the action reversed. He vowed to take a personal role in the fight and has asked two state agencies to scrutinize whether the 99 pension sweeteners are legal and appropriate.

All new state employees, as well as those at most cities, counties and other local agencies across California, will now benefit from the list.

Among the beneficiaries are librarians who help the public find books, secretaries who take dictation, groundskeepers who repair sprinklers and school workers who supervise recess.

“Ninety-nine, are you kidding me?” said Dave Elder, former chair of the Assembly’s public employees committee. “It’s almost impossible to police.”

CalPERS repeatedly told The Times it didn’t know how much the bonuses were adding to the cost of worker pensions even though cities submit detailed pay and bonus information that is used to calculate retirement pay.

Even a small bump in salary can cause a public agency’s pension costs to soar. An increase of $7,850 to a $100,000 salary can amount to an additional $118,000 in retirement if the employee lived to 80, according to an analysis by the San Diego Taxpayers Assn., a watchdog group that scrutinizes city finances.

Fitch, a Wall Street rating firm that weighs in on the financial health of governments, warned that the pension fund’s vote would burden cash-strapped cities.

“Cities and taxpayers will undeniably face higher costs,” said Fitch analyst Stephen Walsh. “Pensions are taking a bigger share of the pie, leaving less money for core services.”

Governments sent CalPERS more than $8 billion last year, an amount that has quadrupled in the last 10 years.

And the cost will continue to rise. Long Beach expects its payments to CalPERS to increase 87%, or $35 million, in the next six years. Finding that money will be “very painful,” its staff recently told the City Council.

Sacramento had been expecting pension costs to rise by millions of dollars when CalPERS asked cities to start paying even more because retirees are living longer. Leyne Milstein, the city’s finance director, estimated the newest jump adds up to an additional $12 million annually — the equivalent of 34 police officers, 30 firefighters and 38 other employees.

At The Times’ request, CalPERS analyzed salary and bonus costs for Fountain Valley — one of hundreds of cities and public agencies that award pension-boosting bonuses to workers.

CalPERS found the Fountain Valley perks could hike a worker’s gross pay as much as 17%. About half the city’s workforce received the extra pay that will also increase their pensions, most of them police and fire employees.

Fountain Valley taxpayers are spending between $147,000 and $179,000 in total compensation, pension and other benefits for each full-time officer on its force, according to city documents. Sergeants, lieutenants, two captains and the chief receive more.

Detective Henry Hsu, president of the Fountain Valley Police Officers’ Assn., defended the bonuses, which he said “are intended to help officers become better officers.”

The money compensates officers for extra hours or hazards they take on in the special assignments, he said.

Fountain Valley City Manager Bob Hall said that most of the premiums are fixed monthly sums, unlike those at many other cities where they are a percentage of base pay — causing them to rise in value with every salary increase.

“We’ve tried to manage the cost as best we can,” Hall said.

CalPERS executives said they don’t understand the anger caused by the board’s vote. The action simply clarifies the 2012 reform law, which was designed to stem rising pension costs, said Brad Pacheco, a spokesman for the agency.

CalPERS always assumed that new employees would continue to benefit from bonuses just as those hired earlier did, Pacheco said. The reform law is still estimated to save taxpayers $42 billion to $55 billion over the next 30 years, he said.

“It’s far-stretched to say this is a rollback of reform,” Pacheco said. “We implement the law as it was written, not how others wish it were written.”

Some public pension funds that operate independently from CalPERS disagreed with its interpretation. Fund officials in Stanislaus and Contra Costa counties decided not to include bonuses when calculating pensions for new employees.

“Our board came to the conclusion that base pay is what the Legislature and the governor had intended,” said Rick Santos, executive director of the Stanislaus County Employees’ Retirement Assn.

Over the years, unions have secured better retirement packages through negotiations with public agencies and by expanding their influence inside CalPERS.

In an extraordinary show of union power, workers persuaded voters in 1992 to amend the state constitution, requiring the pension board to place more emphasis on providing benefits to workers and less on the cost to taxpayers.

In 1993, CalPERS successfully sponsored a bill that gave it the authority to determine what bonuses could be counted toward pensions. That same year, CalPERS created a list spelling out dozens of possible pension sweeteners.

Since then, those bonuses have been used to boost pensions. The 2012 reform law was silent about whether new employees would get them too.

Seven people on the 13-seat board are union members or were elected by government workers who receive benefits from CalPERS. All but one of them voted to add the bonus list into the 2012 reform law.

Union-backed board members weren’t the only ones who voted for the bonuses. State Treasurer Bill Lockyer and state Controller John Chiang both complained about the pension boosters but said they had little choice but to approve them.

“Many of the items on this premium pay list are absolutely objectionable,” said Tom Dresslar, a spokesman for Lockyer. But frustration, he said, “needs to be directed to the proper place, which is the public agencies that negotiated the perks through collective bargaining agreements.”

George Diehr was the only board member elected by workers who voted against the bonuses. A recently retired Cal State San Marcos professor, Diehr said many of the perks seemed silly and archaic.

One thing is clear: Pension costs will keep rising.

San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed, who is fighting to transform the state’s public pension program, said CalPERS is continuing to “work against any kind of reform.”

“They’ve set out on a course to protect the existing system and level of benefits,” Reed said. “Meanwhile, costs are going up, the problem has not gone away, and it keeps getting worse.”

Follow @melodypetersen and @marclifsher on Twitter for coverage of business issues in California.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.