New, more agile robots speed the takeover of jobs once done only by humans

- Share via

At a vast greenhouse in the central Danish city of Odense, a squad of robots moves thin plastic pots of herbs for shipping without even putting a dent in them. For moviegoers used to seeing humanoid machines in action, that might not seem special — but in truth, it’s a remarkable feat.

Robots until recently have been limited to precise, preprogrammed and repetitive heavy-duty jobs like automotive manufacturing. Yet at the Rosborg Food greenhouse, the OnRobot devices adjust on the fly. One pot might be slightly out of position. The next might be a little heavy.

Robots that can see, learn and grip different items are advancing quickly into the retail, food and beverage, and consumer packaged goods industries. While deliveries of robots to the U.S. auto industry fell 12% last year, shipments to food and consumer product companies soared 48%.

“The technology is going so fast now, that in two or three years” says Johnny Albertsen, Rosborg Food Holding’s chief executive, “you can make the robot do almost anything.”

The number of jobs lost to automation is difficult to calculate, in part because one lost position may create several others in new industries. But almost 40% of U.S. workers are in fields — retail and food service, for example — that will lose jobs to automation by 2030, according to a McKinsey report published Thursday.

And robots are needed in many industries where companies struggle to find workers. Unfilled positions in the category that includes warehousing jumped in April to their highest level since at least 2001, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Albertsen expects that improvements in gripping abilities soon will allow robots to pull tender plants from their containers. He plans to expand his crew with more automatons, which pay back the investment in about 18 months. A single setup like the one Rosborg uses typically costs about $70,000, which includes the robot, the OnRobot gripper at the end of the robot’s arm and installation.

The grippers and the machine’s ability to “see” are key. Most heavy industrial robots still operate blindly and must be surrounded by cages to keep humans out of harm’s way. Any variation, such as handling objects with different sizes or textures, weren’t possible. Now grippers that emulate a gecko’s sticky feet, or use soft polymers that expand to apply just the right amount of pressure, allow robots to take on new, more-nuanced tasks.

Cameras let the devices see an object. Artificial intelligence helps them determine the best way to grab it. AI, through which a machine improve its own performance, will prove key for robots to perform tasks that are simple for humans but difficult for machines, such as folding laundry.

At Capacity LLC’s fulfillment center in New Jersey, workers had been tediously scanning items from such companies as cosmetics maker Glossier Inc. and shoe retailer Stadium Goods LLC, then placing each product into one of 16 cubbyholes. The task now is done by a robot arm terminating in three phalanges and an air-driven suction cup in the middle.

Capacity — which packs and ships e-commerce orders from warehouses in France, the U.K., New Jersey and California — has been testing the system from start-up RightHand Robotics Inc., based in Somerville, Mass., and has more devices on order. The return on investment of two years or less helps ease pressure from the tight labor market, says Capacity’s chief strategy officer, Thom Campbell.

“It’s performing well,” he says. “It’s slower than a human, but it does not take pee breaks. It does not go to lunch. It does not only work one shift, and it doesn’t charge for overtime.”

It fundamentally changes everything in robotics. We’re seeing and grabbing. End of story.

— Carl Vause, chief executive, Soft Robotics Inc.

Soft Robotics Inc., based in Cambridge, Mass., makes pliable grippers that can grasp brownies, raw meat, a square box or a cellophane package. That flexibility eliminates the need for complicated coding or costly sensors, says CEO Carl Vause.

“It fundamentally changes everything in robotics,” he says. “We’re not doing very precise, involved path calculations. We’re seeing and grabbing. End of story.

“There’s unbelievable high demand for automation,” he says, especially for groceries, food handling and consumer goods. “These are applications that two years ago, no one would have even considered.”

To meet expanding needs, OnRobot makes a gripper that relies on millions of tiny, gecko-inspired fibrillary stalks that adhere to an object’s surface. The Odense-based company also sells so-called torque-sensor tools that apply just the right pressure for sanding or polishing.

“It’s the ability to pick up a part, to move it,” says CEO Enrico Krog Iversen. “It’s the ability to have hand-eye coordination. The ability to make the robots carry out the same task that we can do as humans.”

Fibrillar stalks and suction cups are great. But some tasks — folding clothes, say, or loading a dishwasher — are still out of reach.

It could take 100 years to match the tiny bones, tendons and nerve endings that make the human hand so versatile, says Junji Tsuda, chairman of robot maker Yaskawa Electric Corp., based in Kitakyushu, Japan.

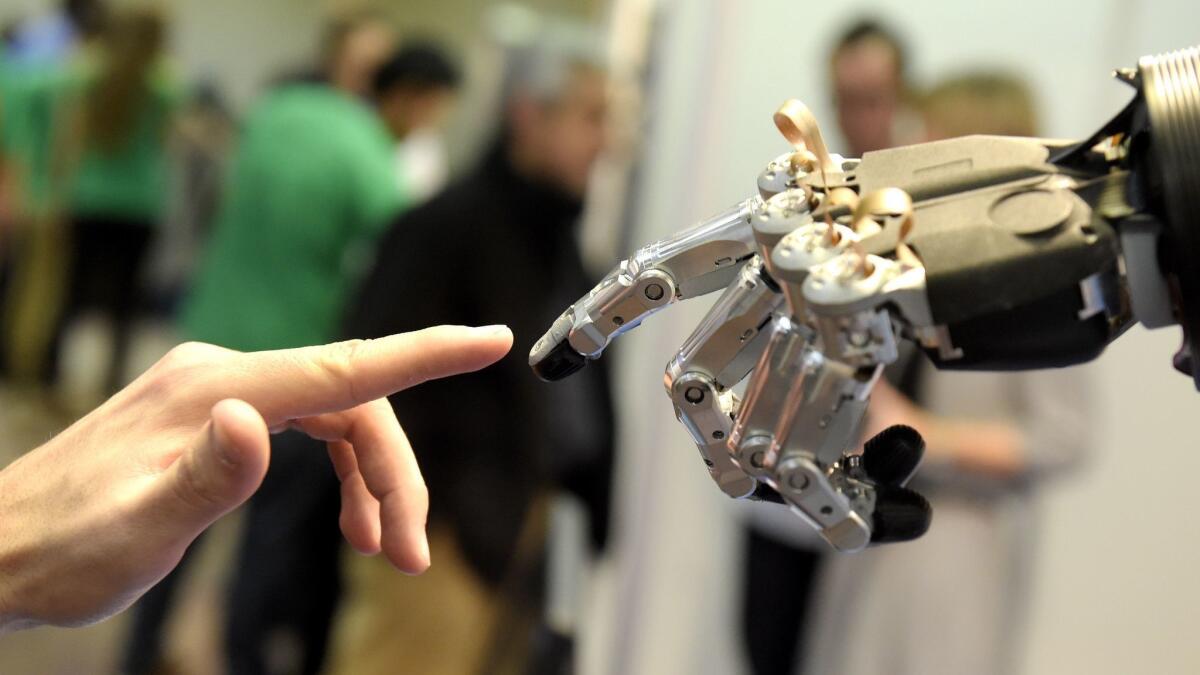

“What would be the ultimate gripper to copy? Well, the human hand,” says Jesse Hayes, an automation group manager at the Schunk company, based in Lauffen am Neckar, Germany. Schunk has designed a tool that looks right — dextrous enough to produce an eerily convincing “come hither” gesture. But at $50,000 each and not rugged enough for heavy industrial purposes, it’s mostly used by researchers.

“In general, for grasping many different objects and shapes and geometries,” Hayes says, “the human hand is ideal.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.