Column: Trump’s plan to throw 3 million people off food stamps shows his cruelty to the poor

- Share via

Fresh from giving its presumed approval to a budget deal increasing federal spending by $50 billion in the next fiscal year and signing a tax cut that will bring more than $1.5 trillion in benefits to corporations and the wealthy over the next decade, the Trump administration moved Tuesday to throw 3 million indigent and working families off food stamps.

The administration says it’s doing this, no joke, to save money — as much as $2.5 billion a year, according to its announcement of the policy change, which will be subject to public comments for 60 days.

Sadly, there’s nothing new about Republican hostility to the food stamp program, which is formally known as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. It’s a rare budget season that doesn’t involve an effort to cut the program by hundreds of thousands of recipients.

As you know there’s a millionaire who’s come out to say he got on the program specifically to prove that he could.

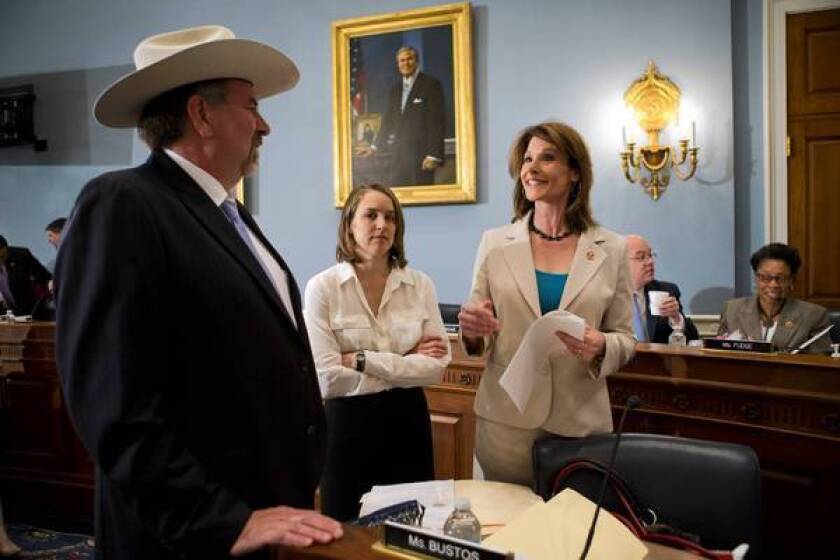

— USDA Deputy Secretary Brandon Lipps

Last year, for example, Republicans tried to cut the program, which costs about $60 billion a year, by more than $17 billion over 10 years. That would have thrown an estimated 1.6 million recipients off the rolls.

In 2013, House Republicans tried to cut $40 billion from the program over 10 years, unashamed that at the same time they were increasing farm subsidies, which many of them were collecting with both hands. (We’re looking at you, Rep. Doug LaMalfa, R-Richvale.)

Republicans and conservatives long have been consumed with the fancy that hordes of Americans are moving heaven and earth to obtain SNAP benefits fraudulently. It’s not as if there’s a pot of gold at stake: The average monthly benefit currently stands at $134.85 for an individual, which works out to about $4.50 per day or $1.50 per meal. SNAP fraud is minimal. According to the Congressional Research Service, about 5.19% of SNAP benefits were overpayments, but only 11% of those overpayments resulted from fraud. That places the fraud rate at about 0.57%. The rest of the overpayments were due to errors by agencies or recipients.

For some reason, conservatives have always harbored a special hostility for the food stamp program.

In the last year, Republicans have argued that their fever dreams about fraud have been validated by the claim of a Minnesota millionaire that he collected food stamps fraudulently, without interference by state officials. The millionaire’s claim is what led to the latest rule proposal. More on that in a moment.

This millionaire is nothing like the typical SNAP recipient. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has documented, 44% of SNAP recipients are children and another 21% are adults who live with those children. Two-thirds of SNAP benefits go to those families, with half of those funds going to households with infants, toddlers or pre-schoolers. These are the recipients targeted by the Trump administration’s policy initiative.

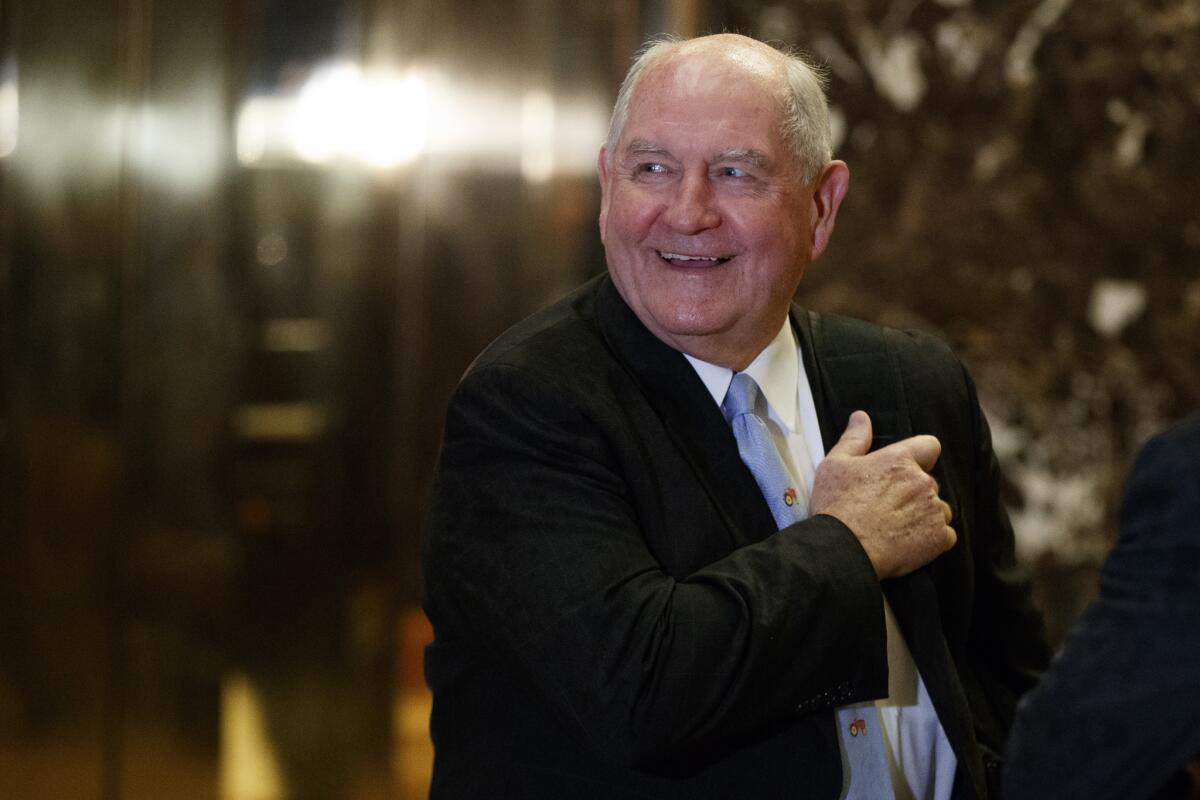

The new policy proposal, issued through the Department of Agriculture, is dressed up as an attempt to close purported loopholes in SNAP. “Some states are taking advantage of loopholes that allow people to receive the SNAP benefits who would otherwise not qualify and for which they are not entitled,” USDA Secretary Sonny Perdue said on a press call Monday, according to Reuters.

The “loophole” he’s referring to is known as “broad-based categorical eligibility,” which allows states to accept residents into SNAP if they’ve already been deemed eligible for assistance through the government’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (TANF), which is what most people probably would regard as traditional welfare, or are receiving cash payments under Supplemental Security Income, a program for low-income, aged, or the infirm.

Broad-based eligibility allows states to enroll residents in SNAP without performing a duplicative income test or checking their assets. But it’s not designed to entirely eliminate income limits. Traditionally, SNAP covers households with income up to 130% of the federal poverty limit (or about $33,500 for a family of four); in some states, broad-based eligibility accommodates households with income up to 200% (or $51,500 for a family of four). Although SNAP asset limits are generally set at $2,250 or less, most states applying broad-based eligibility don’t double-check a family’s assets.

Perdue and other SNAP critics say this system allows states to be entirely too loose about admitting families to SNAP. In some states, eligibility under SNAP can be established through the issuance of an informational brochure explaining the available assistance or referring applicants to other sources of financial assistance. But these brochures aren’t handed out to anyone who wanders into a welfare office; they’re given to people who show up or have been referred because their income meets the TANF guidelines.

Backers of the new farm bill, approved by the House today and destined for consideration by the Senate next week, are patting themselves on the back for saving billions by eliminating a huge wasteful farm subsidy program.

The truth is that there’s no evidence that broad-based eligibility has provided an open door to provide food stamps to significant numbers of ineligible people. When the Government Accountability Office examined the issue in 2012, it found that 473,000 recipients, or 2.6%, received benefits under broad-based eligibility that they wouldn’t have received without the system — but that was largely because many states raised income limits under broad-based eligibility, as they were permitted to so. Those households received smaller benefits than the average. The GAO didn’t find that applicants were gaming the asset rules but, rather, that most fell within SNAP guidelines.

Broad-based eligibility, the GAO concluded, had raised SNAP benefit costs by less than 1%. And that was when the aftereffects of the 2008 crash and the recession were still very much in evidence. Just in the last three years, SNAP rolls have declined by nearly 25%.

That brings us to Rob Undersander of St. Cloud, Minn. Undersander has been getting trotted out by Republicans as a witness to how easy it is to defraud the food stamp system. As he explained in an op-ed in 2016, he deliberately applied for food stamps in Minnesota despite having more than $1 million in assets but, as a retiree, limited annual income. He collected about $5,300 over 19 months to make his point. Instead of returning the money to the government, he says he donated it to charity on the principle that he must know better than state or federal lawmakers about how to distribute financial assistance “because they are giving benefits to us!”

If you’ve been following the food stamp debate in Washington, you know it’s about whether to cut food stamp benefits for the disadvantaged by $4 billion a year (the House proposal) or only $400 million a year (the Senate plan).

Undersander was explicitly referenced by USDA Acting Deputy Undersecretary Brandon Lipps during Monday’s press call. “As you know there’s a millionaire who’s come out to say he got on the program specifically to prove that he could,” Lipps said. “Americans won’t support a program that allows SNAP benefits to go to people like millionaires.” He asserted “there may be other millionaires” getting food stamps.

Since there’s no evidence of that, it’s hard to divine exactly what Undersander’s point is, or that of his GOP enablers, unless it’s that a determined individual can commit fraud on the U.S. government. That’s not news. But the USDA itself knows that millionaires aren’t lining up to collect food stamps in the knowledge that no one will check up on their bank accounts. According to a study the agency commissioned in 2016, only about 6.6% of SNAP households had assets worth more than $10,000, compared to more than 21% of low-income households not receiving food stamps.

The difference between states with broad-based eligibility (that is, no asset test) and those without it was minimal — 6.8% of low-income households in the first group had assets over $10,000, versus 5.1% in the latter group.

The underlying theory of the proposed rule change has nothing to do with keeping millionaires off the food stamp rolls. It’s all about promoting the old chestnut about the “undeserving poor” — those mythical creatures whose straitened economic circumstances are the product of moral turpitude or laziness and, therefore, are claiming benefits that should be going to more deserving individuals. What’s curious about the argument that low-income Americans should have to prove their eligibility for government assistance is that the same demand is never made of the wealthy, who collect tax breaks and corporate welfare by the trillions of dollars.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.