Column: Shell Oil allegedly coerced its workers to attend a Trump rally. Blame the Supreme Court

- Share via

Workers at a Royal Dutch Shell petrochemical plant outside Pittsburgh were coerced into attending a political event featuring President Trump on Aug. 13 on pain of losing overtime pay for the week.

It used to be illegal for employers to dragoon their workers into participating in their political activities. But that ended in 2010, with the Supreme Court’s decision in a case known as Citizens United.

The landmark decision by Justice Anthony Kennedy held that corporations have a 1st Amendment right to make independent political expenditures. On the surface, its principal consequence was to open the American political system to virtually unlimited corporate donations.

NO SCAN, NO PAY.

— A contractor at a Shell facility threatens employees with docked paychecks if they don’t attend a Trump rally

But almost from the inception, legal scholars warned that the decision would allow corporations to turn their workers into a “political captive audience,” as Paul M. Secunda of Marquette University Law School observed in 2010. The bottom line, according to a 2014 editorial in the Harvard Law Review, is that Citizens United “legalized political coercion in the workplace.”

The Pittsburgh event is only the latest example of how this has worked in practice and a harbinger of how it could continue to do so in the future. In 2012, coal baron Robert Murray closed an Ohio mine for the day and allegedly forced the workers to attend a rally for then-Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, who used video from the event in a campaign ad. During the 2012 campaign, several business owners sent letters or notices to workers warning of job consequences if Barack Obama won reelection.

Trump’s evisceration of labor protections will continue under Labor Department nominee Scalia

“What does threaten your job ... is another four years of the same presidential administration,” David Siegel, chief executive of the timeshare company Westgate Resorts, wrote employees. “If any new taxes are levied on me, or my company, as our current president plans, I will have no choice but to reduce the size of this company.” Koch Industries sent notices to employees listing political candidates endorsed by its owners, the conservative Koch brothers.

Political messages from employers to employees have a long and undistinguished history. During the 1936 presidential election, backers of Republican candidate Alf Landon inserted GOP-prepared flyers attacking Franklin Roosevelt and the Social Security Act into pay envelopes, citing the 1% Social Security tax that would be levied starting Jan. 1, 1937: “Effective January, 1937, we are compelled by a Roosevelt ‘New Deal’ law to make a 1 percent deduction from your wages and turn it over to the government,” suggesting the workers would never get the money back.

The Congressional Budget Office, that nonpartisan arbiter of the impacts of federal legislation, reports that raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour would increase the wages of 27 million Americans and lift 1.3 million out of poverty as of 2025.

Roosevelt struck back in a speech on Oct. 31, 1936, thundering: “Only desperate men with their backs to the wall would descend so far below the level of decent citizenship as to foster the current pay-envelope campaign against America’s working people.” (He won reelection in a landslide.)

Murray’s actions raised the hackles of three members of the Federal Election Commission in 2016, but they were unable to obtain the required four-vote majority to proceed with an investigation. In another case involving reported coercion of employees of the United Public Workers union, the FEC failed to assemble a majority to find that the union violated the law.

In the Murray case, the three FEC commissioners argued that while Citizens United permitted corporations “to participate in federal politics to an unprecedented degree,” that shouldn’t mean that “they can use their influence to coerce employees to contribute to causes or candidates favored by management.” But legal experts say there’s no question that the Supreme Court decision undercut federal law protecting workers from coercion.

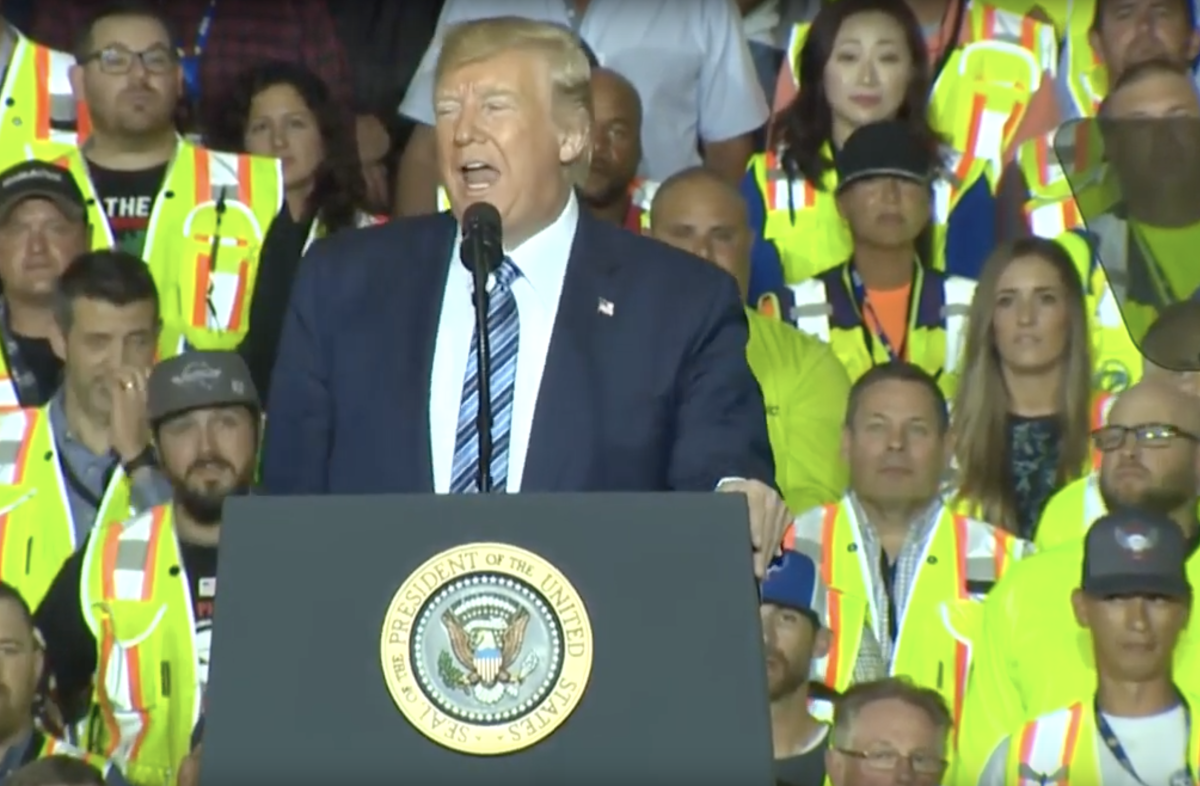

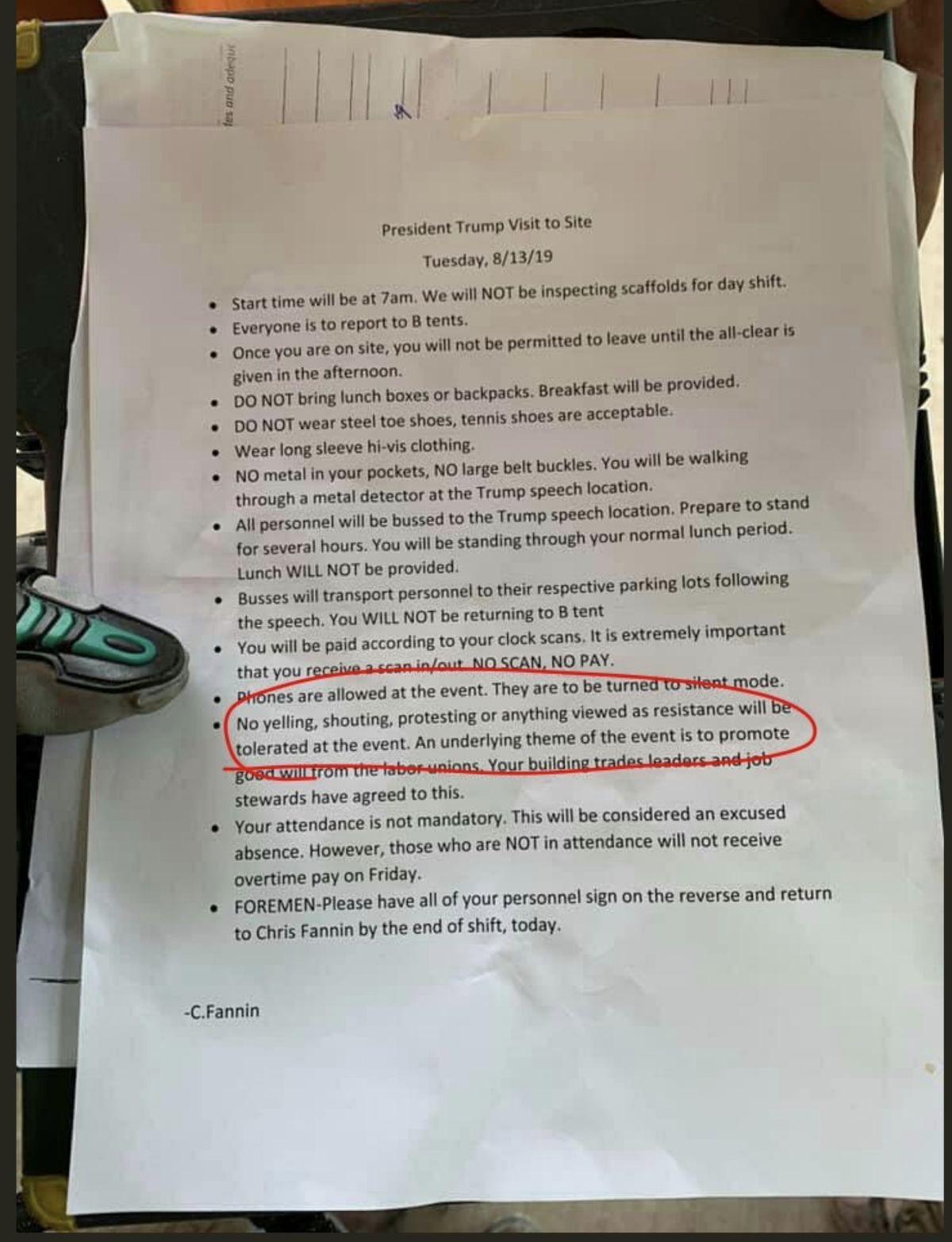

Here’s a quick recap of the Trump event, which took place Aug. 13 at a Royal Dutch Shell facility outside Pittsburgh. As the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported, prior to Trump’s appearance, a site contractor for Royal Dutch Shell sent a memo to union leaders instructing its employees members that members whose attendance was not recorded by time clock scans would not receive overtime pay for the week — “NO SCAN, NO PAY,” it stated. The Post-Gazette describes the memo as “summarizing points from a memo that Shell sent to union leaders a day ahead of the visit.”

A Shell spokesman says that the memo “is not from Shell, nor did it originate from language passed along by the company as it relates to conduct.” The spokesman didn’t respond to a follow-up question about whether other specifications, including those governing pay and attendance, originated from Shell.

(Workers at the site are paid for 56-hour weeks, with 16 hours of overtime built in. Those not attending on Tuesday, consequently, would be paid for the day but wouldn’t receive the 16 hours of time-and-a-half that is normally part of the paychecks.)

The workers were told they wouldn’t be allowed to leave the venue once clocked in, and should expect to stand throughout the event. Although it would continue through their lunch hour, no lunch would be provided. No “yelling, shouting, protesting or anything viewed as resistance will be tolerated,” the memo stated.

Union membership has been declining for decades. Can labor unions be revived? The answer is yes... if.

Shell tried to portray the event as a company “training day with a guest speaker who happened to be the president.” The White House called it an official trip tied to promoting Trump’s energy policies. Video from the floor, however, showed Trump veering into his standard political rally mode.

Trump urged the workers to “support his reelection and to convince their union leaders to do the same,” the Washington Post reported. “‘And if they don’t, vote them the hell out of office,’ he said.”

Prior to the Citizens United decision, the Harvard Law Review observed, a law governing employer political action committees protected workers from political coercion.

Corporations were barred from direct political contributions, encompassing political gifts of “anything of value” — not merely cash, but employee time. They could use a variety of PACs known as separate segregated funds, or SSFs, to collect political contributions from workers, but there were stringent regulations on how employees could be asked to participate.

The law not only “prohibited corporations and unions from dragooning their employees into participation in their political activities,” the law review noted, but also restricted “election-related communications with employees.” Anything resembling job discrimination or financial reprisal against workers declining to participate in employers’ politics was prohibited.

UPDATE, July 12: In its latest report on wages, released Thursday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said that earnings for all employees were unchanged in June from June 2017.

The Supreme Court blew a hole in this system. Because corporations now can participate in politics without resorting to SSFs, the SSF rules no longer protect employees. As a result, the law review observed, “federal law provides no redress for employees who suffer termination or other adverse action as a consequence of their unwillingness to participate in their employers’ political activities.”

The harvest is events like the Pittsburgh rally.

Nothing would prevent Congress from enacting restrictions on employee coercion, the Harvard Law Review concluded. Corporations could still exercise the free-speech rights codified in Citizens United. What would be barred would be conduct — coercing employees or taking punitive action against those who resist.

Will this Congress respond to examples of coercion like Pittsburgh by restoring employee protections? Not this Congress, perhaps, but maybe one in the future.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.