They can’t all be Grand Central Market: Does L.A. have too many food halls?

- Share via

The free-standing collection of eateries at Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade once was stocked with the likes of McDonald’s and Subway. And for years it was enough to attract the tourists and locals that frequent the popular outdoor shopping street.

A few years ago, the two-story collection got a makeover and reopened as Gallery Food Hall with curated offerings including a tiny restaurant operated by a Michelin-starred chef, which requires reservations.

This summer, Gallery Food Hall debuted a “food discovery platform” called Social Eats, which is a sort of food hall within a food hall billed as “where modern cuisine meets a one-of-a-kind community experience, all built upon a foundation of stellar culinary concepts.”

Food halls, those glamorous cousins of brassy shopping mall food courts, have been having a moment for the last decade or so, and the pace of their arrival is picking up. Downtown Los Angeles alone has enough to look like commissary central.

Commercial landlords have increasingly turned to food halls as they jostle to make their buildings stand out in this rough era for merchants. And as more food collectives make the scene, operators must constantly grasp for the unique — carefully curating with grass-fed, farm-to-table fare created by local artisans and keeping things fresh with short-term pop-ups.

Now signs are appearing that Los Angeles and some other major cities may be getting overstuffed.

The number of food halls in the country will nearly quadruple from about 120 in 2016 to about 450 by the end of next year, a recent report by real estate brokerage Cushman & Wakefield said. Once mostly an urban phenomenon, food hall development is expanding into college campuses, suburban office parks and shopping malls, including chef Michael Mina’s planned project at the Beverly Center in Los Angeles.

There have been 10 “notable failures” of food halls in the last four years, the brokerage said, and “it is likely that the failure rate will creep up as more projects proliferate.”

Putting together a successful food hall is hard, but landlords are increasingly tempted to gamble on them because it’s getting more difficult to find desirable merchants to fill their empty storefronts as online shopping thins the retail herd.

“Amazon changed everything,” retail property broker Greg Briest said. “Locations that at one point would have been easy to fill are not anymore. Food halls are an alternate route.”

As landlords contemplate food halls, brokerages such as Briest’s firm JLL are putting together how-to guides for them. Their common inspiration is a century-old food hall in downtown Los Angeles that is considered one of the most successful in the country.

“Everyone in L.A.,” Briest said, “wants a replication of Grand Central Market,” which draws about 2 million visitors a year including office workers, downtown residents and tourists.

Grand Central always offered ready-to-eat fare — early ads for the market show merchants sold edibles such as baked goods, oysters and ice cream — but a previous owner introduced more trendy operators as downtown began an economic renaissance in the 21st century that brought thousands of new residents and visitors to the neighborhood.

Grand Central still sells spices, flowers and produce, but most of its vendors offer prepared meals such as deli sandwiches, fried chicken and ramen. People eat at the vendors’ counters or spread out among tables nearby. In the evenings, visitors meet friends to hang out over beer or coffee in the airy venue wide open to Broadway and Hill streets.

“You can feel that it has a lot of history whether you know about it or not,” said real estate consultant Rick Moses, who oversaw the recent makeover of Grand Central. “Part of the draw of a food hall is the place itself.”

Moses is developing a new food hall in Culver City inside a former newspaper office building completed in 1929 that has elements of Beaux Arts and Art Deco in its design and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The weekly newspaper was called the Citizen and the food hall Moses plans to open in the fall will be called Citizen Public Market. With construction inside the high-ceilinged building on Culver Street well underway, Moses is using knowledge he gained at Grand Central to find vendors. National chains, for example, are out.

“We want folks born and bred into the food scene here in L.A.,” he said, and “people who are socially built for working in a cooperative environment. They have to be willing to work together and accommodate each other.”

At Grand Central, vendors shared recipes and bought ingredients and products such as coffee and bread from one another, Moses said. “I found that to be kind of heartwarming.”

Other downtown food halls include the cavernous Taste Food Hall on Figueroa Street that mixes national chains such as burger purveyor Five Guys with local operators, and the smaller Corporation Food Hall on Spring Street with space for just nine businesses.

Real estate developer Izek Shomof two years ago put the Corporation into the ground floor space of an office building completed in 1916 that was formerly occupied by a sewing machine sales and repair store. It was a holdover from earlier decades when aging structures in the neighborhood were filled with garment manufacturing.

Now Spring Street is in recovery with hundreds of new residential units, renovated offices, bars and restaurants, creating the type of density that food hall developers look for and prompting Shomof to consider opening another food hall elsewhere.

“It’s working for us here,” he said. “Why not?”

Food halls often serve as incubators for restaurateurs who want to test their wings. They may be accomplished chefs who have little background running a business or successful food truck operators who want to level up.

A case in point is Eggslut, which Moses in 2013 brought into a prominent streetside Grand Central stall where previous operators had been unable to prosper. The restaurant was co-founded by veteran chef Alvin Cailan, who had gone out on his own with the cheekily named Eggslut food truck and quickly found an audience for his breakfast sandwiches.

“People wait in line for an hour to get an egg,” Moses marveled.

Eggslut proved to be a draw for Grand Central, and the business grew. Today there are seven Eggslut restaurants, including outposts in London and Dubai.

A more unusual background for an operator can be found in Gallery Food Hall in Santa Monica, where James Beard Foundation award-winning chef Dave Beran opened an exclusive 18-seat restaurant in 2017 called Dialogue that was beloved by the late Los Angeles Times food critic Jonathan Gold and is as hard to find as a speakeasy.

“To get to Dialogue, you walk out of a city parking structure, across an alleyway, and into an ice cream shop whose sticky perfume may remind you of the Santa Monica Pier on a hot July afternoon,” Gold wrote. “You take an escalator to the second level. And you will miss the restaurant the first two or three times you walk by it — the scratched gray door looks like the entrance to a utility closet, and you manage to get into the place only if you remember to pull up the code that will have been emailed to you that morning and punch the numbers into the door.”

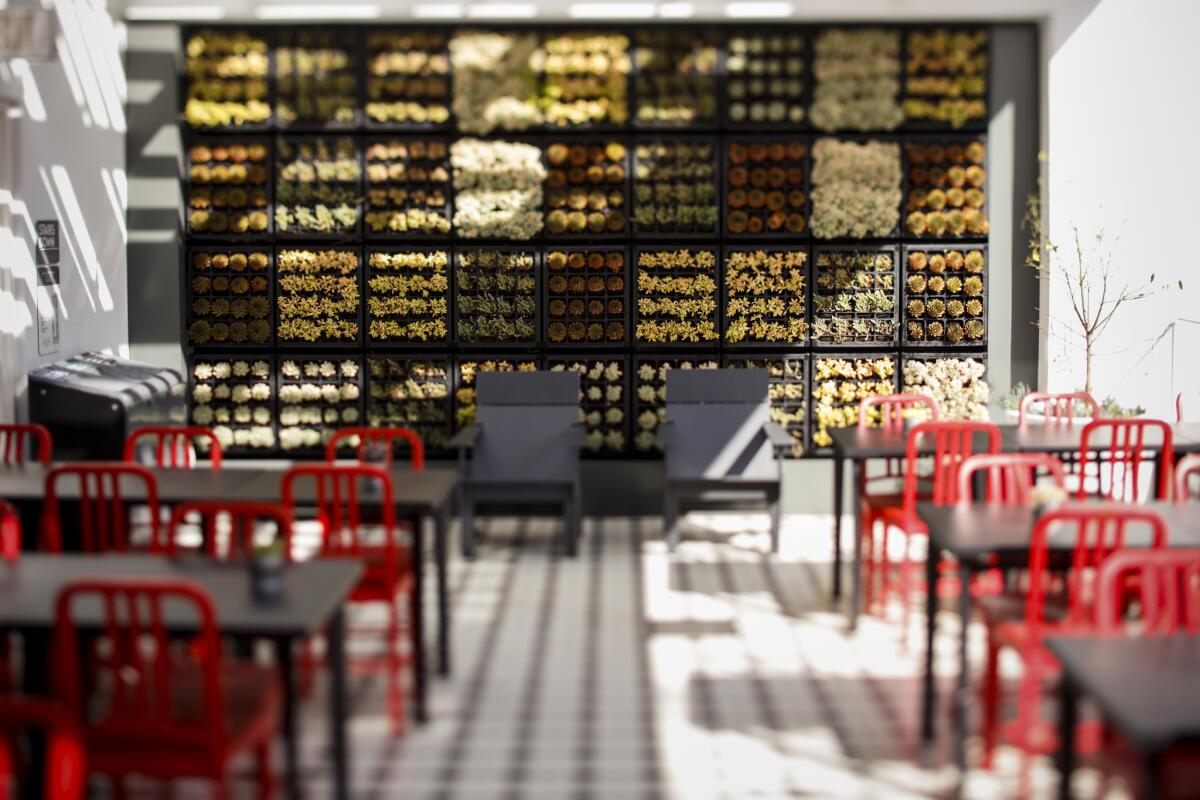

Other restaurants in Gallery Food Hall are more typical of the genre, serving casual fare with an upscale tilt such as swordfish sandwiches and raw sheep’s milk cheese platters. On a recent weekday afternoon, diners who looked like tourists carried their lunch trays of pizza and tacos out to a second-story deck overlooking the promenade.

The fact that Gallery also has a reservations-only restaurant (with a 20-course tasting menu, no less) is far from standard, Briest said, but illustrates the trial-and-error aspect of composing a successful food hall.

California developer Marge Cafarelli estimates that she has had a 35% turnover in tenants since she opened Santa Barbara Public Market five years ago.

Her first miscalculation, she said, was setting out to make the place a European-style public market where people could shop for groceries and other daily necessities at Whole Foods-level prices. It turned out that most Santa Barbarans just wanted to go to their familiar supermarkets.

“We had to pivot,” she said, “and become a bona fide food hall.”

Cafarelli made the grocery space a beer garden and set out trying to find the right mix of tenants selling food and beverages. Her goal was to find tenants that would appeal to locals and not just the tourists some restaurants depend on.

The turning point for Santa Barbara Public Market came in early 2018 when storms followed by catastrophic mudslides in the region displaced hundreds from their homes.

“The one thing we could do was feed people,” said Cafarelli, who hired a local barbecue truck operator to help prepare about 1,500 free meals for the displaced and first responders. “More than the food, really, it was about having a place for people to come.”

Getting the food hall stabilized has been a journey filled with growing pains, she said, such as helping tenants learn how to prosper.

“In my career as a real estate developer, it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done and also the most gratifying,” she said. “It’s like you’ve got to raise this kid. You have to do all the things to set that kid up for success and then the kid has to go out and do it on its own.”

It’s so hard to put together a successful food hall that developers should think twice before trying to make one, Moses said, especially with the existing competition that includes Eataly, a fulsome collection of restaurants and markets under one roof that opened in 2017 in Westfield Century City mall.

“There is very little room for more” food halls, Moses said. “They have to be very special places to be successful. We are past the peak.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.