In-home teeth straightening can save thousands. But brace yourself for the risks

- Share via

Though Anna Rosemond, now 33, had braces when she was young, a couple of years ago she noticed her teeth were again starting to crowd. So when she saw a Groupon deal for SmileDirectClub, she jumped on it.

“I thought, ‘This looks like a really cool way to do braces,’” said Rosemond, who made her own teeth impressions with putty and used a “smile stretcher” ― a device that pulls apart the lips and cheeks ― to take pictures of her mouth. A few weeks after she submitted the items, plastic aligners arrived in the mail, beginning what the company describes as Rosemond’s “smile journey.”

On that trip, there would be no time-consuming visits to a dental office, as her treatment would be overseen online through a SmileDirectClub-affiliated dentist or orthodontist — at a current cost of only $85 a month and a $250 down payment, according to the company’s website.

Initially, she said, the aligners sent in 2017 seemed to be working. But over time, Rosemond said, “my teeth were literally moving at an angle.”

Rosemond is part of a wave of patients who have embraced this do-it-yourself approach to orthodontia, hoping to attain a perfect smile without the high out-of-pocket cost and potential inconvenience of traditional braces or tooth aligners.

Technology enables consumers to do more at home, and dental care ― with its limited insurance coverage ― offers a large potential market. Home teeth-whitening kits have largely displaced in-office treatments, for example. Now, teeth straightening is the newest dental frontier, with start-ups such as SmileDirectClub, Candid, Smilelove and SnapCorrect advertising their services aggressively on billboards and social media.

The DIY approach can yield thousands of dollars in savings. But when the treatment plan doesn’t produce results or goes wrong, consumer-patients such as Rosemond voice their frustrations in Facebook groups and complain to the Better Business Bureau or the Federal Trade Commission that they have nowhere to turn for help.

The companies do not make information public about success rates or problems — although SmileDirectClub says it has achieved a rating of 4.9 stars out of 5 on nearly 58,000 Google reviews — and there are few scientific studies of outcomes for direct-to-consumer orthodontics.

To get a simple refund after an initial 30-day period, patients are often asked to sign what SmileDirectClub calls a “release,” stating the consumer won’t complain publicly — which it says is fairly standard in business. A shareholder lawsuit against the company says those releases suppress consumer complaints, leaving investors in the dark.

Consumer complaints to advocacy groups and regulators, including the FTC, the Food and Drug Administration and state attorneys general, as well as lawsuits, are accumulating.

Regulators, too, are grappling with questions of authority.

The most recent challenge is in California, where Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law that took effect Jan. 1. In his signing statement, he noted that the measure “includes significant policy changes related to the regulation of self-applied orthodontic treatments administered via telehealth and other technological platforms.”

It requires businesses providing dental services through telehealth to make available the names, contact information and dental license numbers of the dentists overseeing customers’ care. In addition, it calls for dentists to review recent X-rays before signing off on a treatment plan. And it will also bar agreements that prevent consumers from filing complaints with regulators.

It’s a question I get asked frequently, most recently by a colleague who was shocked to find that his new pair of prescription eyeglasses cost about $800.

SmileDirectClub, the company with the largest market share of direct-to-consumer orthodontics, says it’s achieving its aim of disrupting the entrenched orthodontia industry.

“We have provided consumers for the first time with an affordable option that is also far more convenient for those who cannot afford to miss school or work or are disabled and cannot get to multiple office visits,” said Susan Greenspon Rammelt, general counsel for SmileDirectClub.

Tiffanie Leatham, who worked as a dental assistant for SmileDirectClub for a year, felt the company pressured her to sign up patients whose teeth she thought were not suitable for aligners. “It was mostly sales with a small hint of dentistry,” she said.

Recent Securities and Exchange Commission filings show SmileDirectClub spent more than half its revenue on marketing.

The direct-to-consumer teeth-alignment industry was enabled by the arrival two decades ago of Invisalign, clear plastic aligners that offered an alternative to the hated “metal mouth” look of braces so familiar to a generation of children. Invisalign, however, is dispensed by dentists or orthodontists during in-office visits, so it’s more costly for consumers.

Although Invisalign sales remain high — its manufacturer, Align Technology, reported a record $2 billion in revenue in 2018 — patents on the product began expiring in 2017.

SmileDirectClub saw the opportunity early and launched in 2014, with backing from Camelot Venture Group, a private investment group that also backed Quicken Loans and 1-800 Contacts. Initially, the start-up’s aligners were made by Align Technology; now, SmileDirectClub does its own manufacturing.

SmileDirectClub, which says it has served more than 750,000 customers worldwide and represents 95% of the at-home clear-aligner industry, went public on Wall Street in September. Its customers almost tripled ― from 90,000 to 258,000 ― from 2017 to 2018, according to SEC filings. The Nashville company has yet to post a profit.

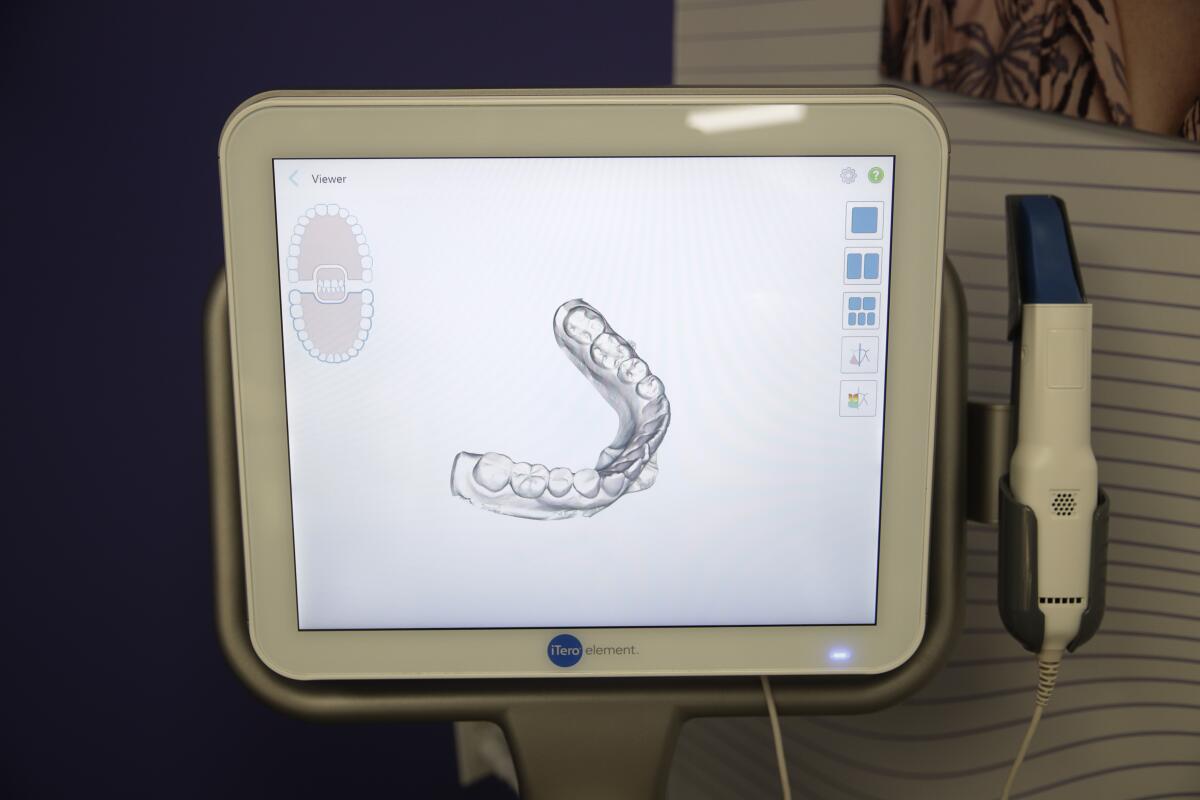

SmileDirectClub said customers initially used impression kits at home. Now, the company said, most customers visit one of more than 360 “SmileShop” locations, some inside CVS or Walgreens pharmacies, where technicians take a 3-D scan of their mouths. The total cost starts at $1,895, although financing or additional items, such as retainers, can add to the price, according to the company’s website.

Those impressions, photos and scans are sent to SmileDirectClub’s facility in Costa Rica, where technicians develop treatment plans and one of 85 dentists employed there reviews it. For U.S. customers, treatment plans are also reviewed by a dentist or orthodontist licensed in the state where the customer lives, SmileDirectClub says.

Customers then receive an image of what their teeth might look like after treatment and can decide whether to proceed. If they do, the facility sends off the plastic aligners, which are worn sequentially over a few months for 22 hours a day.

If there is a question or problem with the aligners, billing or other issues during the months-long treatment process, customer service agents are the first stop. They can route concerns to the affiliated dentists, company executives said. Sometimes, according to a written statement, “the treating doctor will ask to see the patient in person, or work with the patient’s regular dentist.”

In the same statement, SmileDirectClub said it could not comment directly on specific patients’ experiences.

Direct-to-consumer aligners are clearly filling a niche, but one that makes some healthcare experts uncomfortable. “It’s a symptom of a broken healthcare system: getting dubious-quality online services without much accountability because mainstream services are unaffordable,” said Arthur Caplan, founding head of the division of medical ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York.

As the industry has grown, so too have complaints from customers, pushback from dentistry’s professional trade groups and scrutiny from regulators. More than 1,600 complaints have been lodged nationally against SmileDirectClub with the Better Business Bureau in the last three years. The FDA has received at least 72 complaints regarding SmileDirectClub’s products since 2017, according to a Kaiser Health News analysis of the agency’s device database.

KHN contacted all 51 state attorneys general offices. California’s declined to share the number of complaints received so far, saying “it’s not our practice to comment — even to confirm or deny — a pending or potential investigation.” But, of the 34 offices that responded to the request, 19 reported a total of 75 complaints concerning SmileDirectClub. The FTC also has received 175 complaints against the company, though the majority (148) are duplicates of the complaints received by the BBB and the state attorneys general. SmileDirectClub’s Instagram and Facebook posts also have generated many comments from dissatisfied consumers.

The other companies, all with far less market share, also figure in complaints filed with the BBB, including 54 against Candid, 10 against Smilelove and three against SnapCorrect.

Despite that, the BBB says it gives all the companies high grades because their business volume is high compared with the number of complaints filed and they demonstrate responsiveness to complaints. SmileDirectClub maintains an “A-minus” rating from the bureau. The other companies range from A to B-minus.

Many of the BBB, FTC and social media complaints focus on customer-service issues, such as delays in receiving products or difficulty in obtaining answers to questions about treatment or getting refunds. Only a sliver of complaints ― 48 ― submitted to the BBB’s website centered on clinical problems, Dr. Jeffrey Sulitzer, SmileDirectClub’s chief clinical officer, said in a November interview.

One was lodged by Michael Anthony Johnson, 57, of Dallas, who alleges the company’s aligners harmed his teeth. Johnson, chief executive of online Centertainment Radio & TV, said he saw the advertisements and stopped in at a SmileDirectClub retail location to see if he would qualify. A technician took a 3-D scan of his teeth.

“She said, ‘I think you’ll be fine,’” he recalled. “Two days later, I was approved.”

For the first few months, all seemed well; but at month seven, several of his teeth broke, he said.

SmileDirectClub responded that the initial scans taken in their shop showed problems before he started treatment, including two broken teeth, fractures on one and a dark spot on another. “Before you started remote clear aligners these areas of concern should have been addressed with your local dental provider,” Charlene, with the company’s dental team, wrote in response, according to the BBB website.

She also noted that Johnson had signed a consent form for his aligners, a document that includes one long paragraph declaring he had recently been to a dentist and taken care of any problems. Johnson said he did not read the multi-page document before signing.

“The response back to me was, it’s your fault,” Johnson said. “No one said you need to go see the dentist. Yes, it’s my fault for not reading the fine print, but the person taking my imprints, she never mentioned it.”

Johnson is now saving up money so he can get three teeth replaced with implants. For some, he said, the aligners may be a great product, but “I know, for me, it was not.”

The company has argued it isn’t liable for clinical problems raised by consumers, as it is not practicing dentistry but is merely a “dental support organization” ― essentially, the go-between. Rather, SmileDirectClub said its treating dentists and orthodontists are the responsible parties if something goes wrong.

Those treating dentists and orthodontists ― who earn an average of $50 per customer ― can review patients’ files, ask the customer to submit more information or seek X-rays and even request that the patient get a deep cleaning before treatment, said Greenspon Rammelt, SmileDirectClub’s general counsel.

However, SmileDirectClub dentists do not see the patient in person, and some experts say that is a problem.

“A proper diagnosis cannot be done by a picture of teeth,” said Chad Gehani, a practicing dentist and the American Dental Assn.’s president. An examination, he added, is needed to detect things such as cavities, shortened roots and gum disease, which could lead to problems, according to the ADA and the American Assn. of Orthodontists. Both groups discourage the use of online aligners.

SmileDirectClub announced Jan. 14 that it would soon offer aligners through dentists and orthodontists.

Several lawsuits challenging SmileDirectClub — brought on behalf of consumers, dentists and shareholders — are ongoing.

One class-action case brought by dentists, orthodontists and consumers in Tennessee alleges the company engages in false advertising and unfair trade practices, although all of its consumer plaintiffs have withdrawn as of this month. SmileDirectClub had won a ruling that its customers all sign agreements to arbitrate disputes, rather than litigate. Shareholder lawsuits allege SmileDirectClub failed to disclose some concerns, including the level of consumer complaints, before the company’s initial public offering.

In separate action, after dental boards in Georgia and Alabama set rules requiring dentists oversee any scans done in retail settings, SmileDirectClub went to court. In its filings, SmileDirectClub alleges the boards, made up mainly of dentists and orthodontists, were trying to stifle competition.

SmileDirectClub has also sued the Dental Board of California, arguing it directed an investigator to “conduct a series of coordinated raids” on its retail stores that amounted to harassment.

The California case is pending in federal court. The Georgia and Alabama cases are also ongoing, pending before the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals.

The cases have drawn much interest: The American Assn. of Orthodontists has filed amicus briefs in support of the Georgia and Alabama dental boards, backing their jurisdiction and authority to set rules. The Federal Trade Commission weighed in on behalf of SmileDirectClub on a part of the case that involves whether Alabama state lawmakers exercise enough supervision over the state’s dental board.

As for Anna Rosemond, after sending multiple photos of her teeth to SmileDirectClub via Facebook Messenger, she said she was told to complete her treatment, despite her concerns about her teeth moving at an angle. Eventually, the company agreed to send her new aligners, but she said they didn’t fit.

Fed up, Rosemond said, she stopped her credit card payments to SmileDirectClub. She ignored calls and emails about being sent to collections.

She said she consulted an orthodontist who told her, based on his review of previous X-rays and photos, she had a crossbite because of the SmileDirectClub treatment and would need braces with rubber bands to correct the issue.

She recently finished nine months of traditional orthodontics treatment from that orthodontist and loves her smile now that the braces are off.

“I’m so much more confident,” Rosemond said. “And my bite feels great.”

Appleby and Knight write for Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent publication of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.