For Silicon Valley tech tycoons, angel investing is a status symbol

- Share via

Adam D’Angelo could have retired when he left Facebook at the age of 23. Instead, the social network’s former chief technology officer, who saw his Facebook stake soar in value to over $100 million after the company’s 2012 initial public offering, enthusiastically threw himself into a career as a tech entrepreneur. He made dozens of investments in start-ups and founded his own venture, Quora, the world’s leading question-and-answer site.

As he once said in an interview: “I felt I could make a bigger impact on the world by starting something new, rather than just continuing to optimize Facebook.”

For the record:

11:03 a.m. Feb. 26, 2020An earlier version of this article misstated Melissa Bender’s comments on special-purpose investment vehicles.

It might have been easier to sit on the cash. With D’Angelo as chief executive, Quora has established itself as a global market leader in Q&A, and is now worth almost $2 billion. But it has not been without its problems, not least recent layoffs among its 200 staff.

D’Angelo’s approach is representative of a new generation of tech executives coming to terms with financial success. The decades-long boom in technology has created riches at historically unprecedented rates, turning recent university graduates into youthful billionaires.

Wealth advisors say that most people in the technology sector are unprepared for the changes that come with riches. But they are learning fast and developing a risk-on style that marks them out as a class apart among the rich.

Starting in the 1980s with figures such as Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, technology had created 89 U.S.-based billionaires by the end of 2018, including 19 in that year alone, according to an analysis by UBS, the Swiss bank.

Founders’ deputies have also shared in the wealth creation, with nearly 130,000 start-up employees in the U.S. being millionaires based on the value of their company shares and options, according to Carta, an equity-management software provider. Of those, 15,000 are worth more than $10 million, and more than 1,000 have crossed the $100-million threshold.

“They go from ramen and a studio apartment to being one of the wealthiest people in the country overnight,” says Roy Bahat, head of Bloomberg Beta, a venture firm backed by the financial information company. “I don’t know if we have the precedent” for that happening to thousands of people, he adds.

Like other wealthy entrepreneurs cashing in their shareholdings via stock market flotations or other exit routes, they buy houses, luxury cars, perhaps yachts. Larry Ellison, Oracle’s billionaire co-founder, has taken that to the extreme by sponsoring a team in the America’s Cup, the world’s most expensive sailing race.

They also invest in property — especially on the West Coast — and traditional stocks and shares. Through his investment company Cascade Investment, Gates was once even a shareholder in Carpetright, a decidedly unglamorous British flooring retailer.

Family offices have been established, executive assistants have suddenly become chiefs of staff and philanthropic plans are being implemented, in ways that would look familiar to private bankers in New York, London or Zurich. But the tech generation still stands out for its willingness to pump money back into the industry. Entrepreneurs go for nascent ventures, often run by friends and acquaintances in Silicon Valley, teaming up with other cash-rich tech businesspeople and venture capitalists.

Recently signs of caution have emerged, with some potential investors worried that the long tech boom may have run out of steam as valuations wobble at some of the largest start-ups. The skeptics see a loss of momentum following the boost provided by low interest rates in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, which encouraged investors to plow in cash.

But for most, the appetite for tech is as big as ever. Investors have given more than $210 billion to Silicon Valley-area start-ups in the last decade, representing nearly 30% of all the money given to start-ups during that period, according to estimates by EY, the business advisors.

“People here are very comfortable with losing money on their investments,” says one Silicon Valley-based wealth advisor. “In San Francisco, this is a form of charity. It keeps the whole ecosystem working.”

The growth of the billionaire economy is likely to be debated in the presidential campaign.

When start-up executives cash out, they often base their personal investments on the venture capitalists’ model, looking for promising start-ups. These investors become “angels,” writing $100,000 checks, sometimes via special-purpose vehicles that allow them to pool their resources.

“One of the things that happens in Silicon Valley when people make money is they want status. Angel investing is the status marker, whereas in other places it is giving,” says Bahat, noting that high-profile tech founders often end up investing in one another’s companies.

Wealth managers around San Francisco say their clients keep between 5% and more than 60% of their wealth in these investments. That range stands in contrast with the broader universe of family offices, which on average put 11% of their capital in direct private-equity investments, according to UBS.

John China, president of SVB Capital, a Californian investment company, says he has seen angels with upward of 50 investments, discovered largely through their Silicon Valley networks.

“They tend to take more risk with angel portfolios and don’t really track them or worry about them,” says China, whose company is part of Silicon Valley Bank, a big lender to start-ups and venture capital funds.

The portfolios can be lucrative.

Amazon Chief Executive Jeff Bezos, for instance, was one of the first investors in Google, putting in $250,000 in 1998. His stake, purchased for 4 cents a share, would have been worth more than $500 million at Google’s IPO in 2004.

Another huge second-generation bet to have made it to a public listing is electric car maker Tesla, whose chief executive and biggest investor is the audacious Elon Musk. He made his first tech fortune from the 2002 sale of payments group PayPal for $1.5 billion to EBay (Musk held 11.7% of the shares).

Many of the tech elite have their sights set on the sky and beyond, including Musk with rocket maker SpaceX. Bezos founded aerospace company Blue Origin; Paul Allen, the late Microsoft co-founder, started Seattle-based Stratolaunch, a space transport venture; Sergey Brin has put his weight behind a zeppelin-like airship; and Larry Page, who co-founded Google with Brin, has backed Planetary Resources, an asteroid-mining venture, and electric aircraft maker Kitty Hawk.

The tech super-rich spread their bets, investing through family offices with their own investment teams. Vulcan Capital, Allen’s family office, counts 57 private investments on its website, including early stakes in Chinese e-commerce group Alibaba. Bezos’ investment group, Bezos Expeditions, has made 26 disclosed venture investments, including stakes in Airbnb and Uber.

Some bets are already paying off and some are a gamble on the distant future. Some have already run into difficulties. The family office of Oracle’s Ellison made headlines in 2017 with an investment in Japanese conglomerate SoftBank Group’s $100-billion Vision Fund, the largest tech venture investor. But, more recently, the fund’s approach has been questioned in light of financial difficulties at one of its biggest investments, the co-working group WeWork.

Multifamily offices, which manage investments for multiple wealthy individuals, also provide capital for start-ups. Iconiq Capital manages $13.9 billion of assets and advises on another $18.8 billion for Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg and fellow executives, according to filings from the end of 2018. The firm has invested in private tech companies through an unconventional structure combining a traditional family office with separate registered funds that are open to external investors such as sovereign funds. The firm has also introduced those external investors and start-up founders to tech executives.

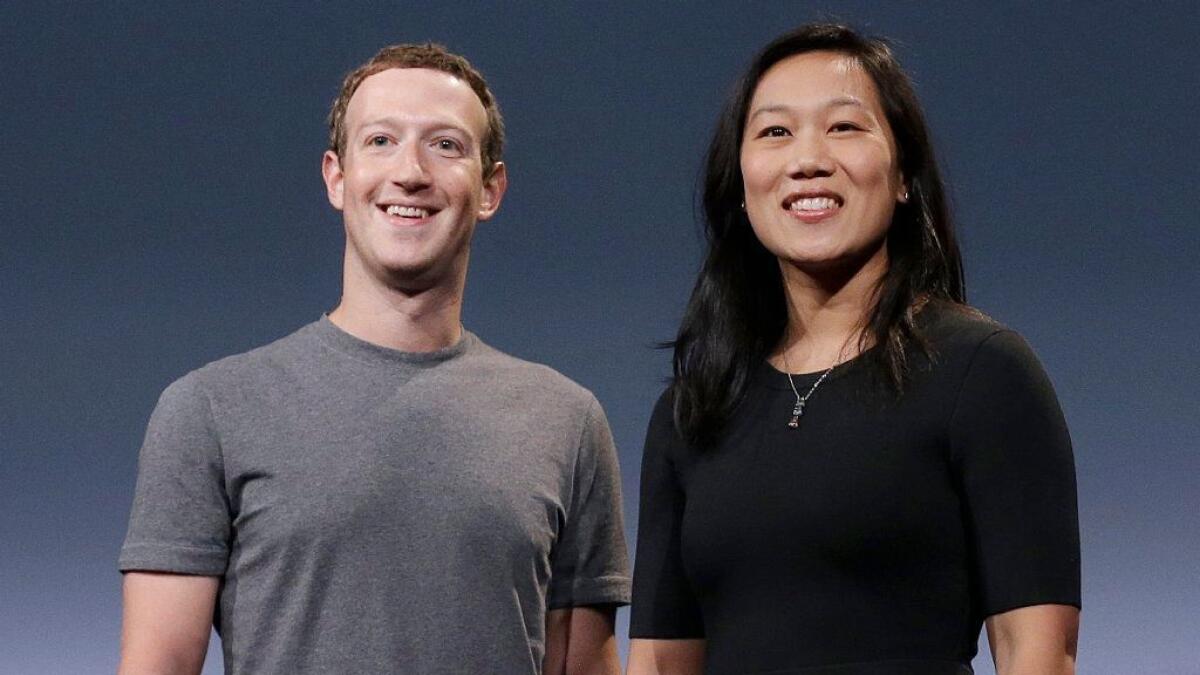

Some investments are difficult to distinguish from charitable grants, blurring the lines between profit and philanthropy. Zuckerberg pledged up to $1 billion a year to a controversial organization spreading money across grants, political donations and start-up investments. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, co-founded with his wife, Priscilla Chan, has called itself “a new kind of philanthropy,” registering as a limited liability company. When Zuckerberg committed 99% of his Facebook stake to the group in 2015, those shares amounted to more than $45 billion in value.

Laurene Powell Jobs, the widow of late Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, has also set up her “social change organization” Emerson Collective as an LLC. Its investments range from the magazine the Atlantic to the supersonic jet start-up Boom. According to data provider PitchBook, Emerson Collective has made 48 venture capital investments since 2013, alongside its other philanthropic work.

Powell Jobs is only one of several tech billionaires who have invested in the media, at least in part to ensure press freedoms.

Bezos, who bought the Washington Post in 2013, has said he believes the newspaper “has an incredibly important role to play in this democracy,” though the arrangement has been criticized by press watchers wary of the influence he could exert over the institution’s output.

Bahat of Bloomberg Beta says traditional nonprofits have lamented the difficulty of raising funds from wealthy tech executives, so they need to try new approaches. He has begun hosting events where millionaires from recent IPOs discuss productive ways to grow and disburse their wealth.

“In a way, it’s really nice because they don’t put on airs,” says Bahat. “And in a way, it’s really weird because they don’t know what to do.”

After amassing $3.6 billion from selling WhatsApp to Facebook for $22 billion, co-founder Brian Acton opted to funnel money into another encrypted messaging app, the nonprofit Signal. He did, however, walk away from stock options worth $850 million following a disagreement over the monetization of WhatsApp; he also joined the “#deletefacebook” campaign.

Jan Koum, the other WhatsApp co-founder, shifted his focus to more conventional super-rich pastimes after the 2014 sale, posting that he would be “collecting rare air-cooled Porsches, working on my cars and playing ultimate Frisbee.”

Gates’ Cascade has also taken a more conventional route — in investment terms — and has compiled an active stock portfolio reminiscent of hedge funds, alongside out-of-favor property holdings. Iconiq has become a significant investor in data centers, which, though high-tech, are relatively low-risk infrastructure investments.

This more cautious investment approach, where wealth preservation takes priority over investment growth, is becoming more common in Silicon Valley. Wealth advisors say tech multimillionaires have begun asking pointed questions about the long bull run for stocks, including the tech companies from which they made their fortunes.

Start-up founders are also starting to cash out increasing sums from their businesses earlier in their life cycles, fearing that the flood of capital into the industry may not last if the likes of SoftBank and sovereign funds beat a retreat.

Melissa Bender, a San Francisco-based partner at law firm Ropes & Gray, says some special-purpose vehicle structures used by angel investors might even contravene securities regulations, noting that high-profile angels sometimes charge fees to arrange deals.

Securities and Exchange Commission rules require that investment advisors register or qualify for an exemption from registration and that persons paid transaction fees comply with broker-dealer requirements.

Bender says many young tech entrepreneurs are used to their industry’s relative lack of regulation compared with asset management.

“These are also folks who have been rewarded for being willing to take on a lot of risk,” she adds.

Four out of five paper millionaires are men, a study finds.

One wealth advisor has observed a shift by tech founders away from angel investments. Instead, they are putting money into more mature companies alongside blue-chip venture capital firms such as Benchmark Capital and Sequoia Capital.

Jennifer Forster, a partner at San Francisco-based wealth manager Epiq Capital Group, says investors recently have been able to sell shares at high prices in secondary markets, allowing them to cash out significant portions of their stakes.

“After a 10-year bull market, there is a feeling that ‘maybe I should monetize while I can,’” she says. “But the flip side is you have people who are building these tremendous companies that are growing at 150% a year. There aren’t many assets like that where you’re able to invest.”

Epiq, which was spun off from Iconiq in 2018, manages more than $2 billion for about 50 wealthy families, including tech founders in the San Francisco area. The firm tends to accept families with at least $50 million to $100 million of investable wealth and becomes involved in their lives, handling matters such as the privacy of their donations and home purchases, Forster says. She says Epiq aims to be a long-term investor and thinks there is still more “alpha,” or outperformance, available to investors in private markets.

Helen Dietz, a principal in Mountain View, Calif., for the financial advisor Aspiriant, says some of her clients reserve as much as a quarter of their portfolios for investment in start-ups and other speculative ventures. But one of her younger tech founders has set aside only about 10% for such stakes, she says, noting that her clients tend to view such personal investments as profit-making opportunities, rather than primarily about status or altruism.

Tom DeFilipps, a lawyer at Covington & Burling in Palo Alto who advises start-up founders, says he has seen little decline in Silicon Valley’s appetite for risky investments.

“You have all of this wealth, and there’s just a limited amount you can do with it within the confines of the way people behave in Silicon Valley,” he says. “There’s not a lot of outsized demonstrations of wealth here.” He notes that his clients still ask him: “What else am I going to do with my money?”

© The Financial Times Ltd. 2020. All rights reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

What the tech billionaires buy

Jeff Bezos

Fortune from: Amazon

Worth: $117 billion

Has invested in: Blue Origin (aerospace), Uber, Washington Post

Sergey Brin

Fortune from: Google

Worth: $66.3 billion

Has invested in: Tesla, ‘Lighter Than Air’ airship

Laurene Powell Jobs

Fortune from: Apple

Worth: $27.3 billion

Has invested in: Disney, Emerson Collective (social impact), Boom (aerospace), the Atlantic (publishing)

Elon Musk

Fortune from: PayPal

Worth: $29.7 billion

Has invested in: SpaceX, Tesla

Mark Zuckerberg

Fortune from: Facebook

Worth $83.1 billion

Has invested in: Vicarious (artificial intelligence), Asana (software), Iconiq Capital

Bill Gates

Fortune from: Microsoft

Worth: $113.9 billion

Has invested in: Beyond Meat (plant-based food), Four Seasons Hotels, TerraPower (nuclear energy)

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.