Column: In coronavirus bailout of airlines, here’s what we should demand in return

- Share via

It’s probable that not even the Atomic Clock has the ability to keep up with the speed with which major American corporations extended their hands for government bailouts in the novel coronavirus crisis.

So far, we’ve heard from the airline, hotel, casino and cruise ship industries, all of which assert that they’re facing immense losses and even bankruptcy as the lockdown of American and international economies take hold.

Surely there will be more, since the Trump administration has been signaling its willingness to listen.

This is not a bailout. This is considering providing certain things for certain industries.

— Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin

“We’re going to back the airlines 100%,” President Trump said Monday. “We’re going to be in a position to help the airlines very much.”

The nature of that help isn’t yet clear, though the airline industry has asked for $60 billion in help, including $25 billion in direct grants plus loan guarantees and tax rebates and repeals.

The list is already growing, ranging from aviation, which could make a case, to retailers, who have asked to an immediate lifting of tariffs on Chinese goods, to you-gotta-be-kidding-me appeals from consumer goods companies selling food, personal care, hygiene, cleaning and disinfecting products, which in fact have been flying off the shelves.

The Consumer Brands Association, which includes Procter & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive and General Mills among its leading members, asked Trump this weekend for emergency funds to “mitigate supply chain disruptions,” which sounds like they can’t make and ship product fast enough to keep supermarkets stocked. If ever there’s a problem an industry should be happy to have, that’s it.

It’s fair to say that some industries might indeed need government assistance to get over the emerging economic slump. The question is, what does the American public get in return?

Saying that the survival of these industries should be reward enough won’t do. Unlike such small businesses as restaurants and bars, which have been shut down in parts of the country by government order and were facing huge drops in patronage anyway, most of the hardest-hit major industries have the capacity to survive one way or another.

But no government help should be provided without strict oversight about how it’s used. That’s warranted because American industry has grossly misused its previous handouts, fattening shareholder returns and executive pay while leaving employees aside. That can’t happen again.

Some employers are adding sick leave amid the coronavirus outbreak. Others are leaving workers hanging.

That’s the theme of a statement Monday by Sara Nelson, president of the Assn. of Flight Attendants, which represents 50,000 airline employees. In a series of tweets, Nelson acknowledged that the airline industry could face a crippling setback from the coronavirus emergency.

She called for “direct payroll subsidies to workers in the passenger airline industry,” including “flight attendants, pilots, airline ground workers, airline caterers, airport cleaners, greeters, security screeners, wheelchair attendants, and other airport service workers. Anyone who touches aviation.”

Those subsidies may well be subsumed into a stimulus plan being worked out on Capitol Hill on Tuesday by congressional leaders and Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin.

But Nelson wisely is seeking specific guarantees to ensure that government money flows to the workforce: “Airlines must commit to maintaining payroll,” she wrote. “It means no bonuses, no buybacks, & no breaking union contracts in bankruptcy. Companies should commit to pay a min $15 wage & board seats for workers.”

That’s as good an outline of the mandates as one could hope for. The current crisis could present a unique opportunity to reverse the decline of labor’s voice in American business practice. Setting minimum wages and raising the bar for layoffs is a good start.

Prohibiting the use of government help to pay executives or raise returns for shareholders is mandatory, along with preserving union contracts.

Past bear markets bequeathed us a host of investment maxims (but they were often wrong).

Airlines and all other recipients of government largess should be required to commit to noninterference with union organizing in their shops and to welcoming labor representatives onto their boards. If any industry needs to be put out of business as a result of the crisis, it’s the union-busting business.

Let’s be clear what we’re talking about. Mnuchin, in congressional testimony March 11, rejected the term “bailout.” He said, “This is not a bailout. This is considering providing certain things for certain industries.”

In other words, a bailout.

Nelson’s suggestion of an oversight board with subpoena powers and representatives from management and unions is a good one, too. We don’t need guesswork to know how corporations will spend their bailouts if they aren’t watched like hawks. Past experience tells the tale. Take the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the massive giveaway to corporations and the rich enacted by the Republican-controlled Congress and signed by Trump in December 2017.

The tax cuts would produce a massive spur to U.S. economic investment, yielding fortunes in economic growth, the proponents said. “It will be rocket fuel for our economy,” Trump promised.

Didn’t happen. To be more precise, the short-term spurt in growth dissipated faster than a sugar high from Jolt Cola. One reason certainly was that businesses didn’t fulfill the promise of pumping their tax breaks into investment — whether capital investment or investment in their workforces via higher wages.

Sure, not a few employers funneled some money to their workers, generally via onetime bonuses. Companies announced these payouts as though they signified the bounty brought by the tax cut bill, but in fact they were cheeseparing handouts that, unlike wage increases, weren’t lasting; in most cases they didn’t even approach the $1,000 headline sums the companies claimed.

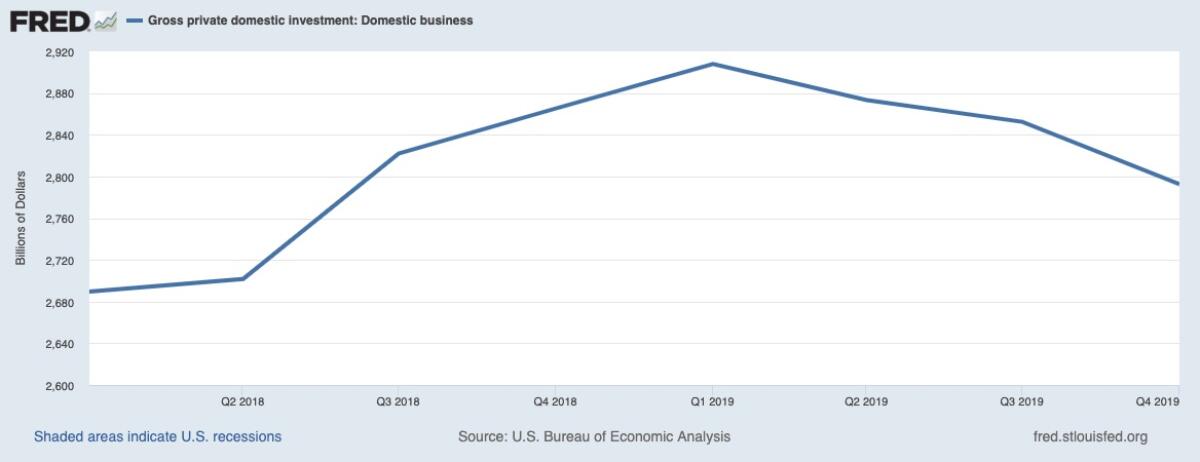

As for capital spending, this was also evanescent. Gross private domestic investment rose from $2.7 trillion in the first quarter of 2018, as the tax cuts took effect, to $2.9 trillion a year later. That was its high water mark; it was down to $2.8 trillion in the last quarter of 2019.

The coronavirus shows why Trump’s healthcare policies are dangerous for all

The vast majority of businesses — 84% of respondents to a January 2019 poll by the National Assn. for Business Economics — had made no change in their hiring or investment plans as a result of the tax cuts. By December 2019, a leading index of new capital orders had sunk to its lowest level since August 2016, raising fears for economic growth in 2020.

So where did the money go? Mostly in share buybacks, a neat way for corporations to pump money out to their shareholders. In the third quarter of 2018, buybacks by Standard & Poor’s 500 companies reached $203 billion in those three months alone — the first time quarterly repurchases exceeded $200 billion. In the year ending September 2019, they came to almost $800 billion.

No one has a right to be surprised at this outcome. It merely replicates what happened after the previous major giveaway to corporate America, a 2004 tax holiday designed to prompt corporations to bring home profits they had parked overseas.

The idea was for them to spend the money on jobs and domestic investment. Instead, they spent the money on stock buybacks to benefit their shareholders and fatten executive pay. A Senate subcommittee report in 2011 determined that the 15 biggest companies taking advantage of the tax holiday, including Pfizer, Hewlett-Packard and IBM, actually cut jobs and reduced research spending. The treasury lost $3.3 billion in revenue over 10 years, the panel found.

“There is no evidence that [the tax break] increased U.S. investment or jobs, and it cost taxpayers billions,” a U.S. Treasury report determined. After the tax holiday, U.S. corporations even stepped up their sequestering of profits abroad, figuring that sooner or later a new administration would offer them yet another break. That’s exactly what happened: A discounted tax rate on repatriated funds was a central element in the 2017 tax cut bill.

By limiting sick leave and free healthcare, the U.S. system will promote the spread of coronavirus.

Airlines have been among the big spenders on their own shares. As Bloomberg reported this week, America’s major airlines spent 96% of their free cash flow on share buybacks from 2010 through 2019. That included United, which launched a $3-billion share repurchase in December 2017, as the tax cuts were nearing congressional approval. That was on top of a $2-billion program it had completed that very month.

Those figures should give some color to the appeal sent by United Chief Executive Oscar Munoz to Mnuchin and congressional leaders Monday. In his letter, Munoz pleaded for the government to “offer support to the men and women of United Airlines. ... Financial support that you provide would allow United to continue paying our employees as we weather this crisis — protecting tens of thousands of people from imposing a temporary furlough.”

You would almost think that the company’s concern in shoveling out $5 billion via share buybacks was for its rank-and-file workers, rather than its shareholders.

The airlines arguably were especially foolhardy in diverting to shareholders’ pockets the surge in profits they collected over the last 10 years, a post 9/11 golden age for air travel. Few industries are as trapped in a permanent boom-and-bust cycle as the airlines, which are continually buffeted by fuel costs and intense competition.

As Tim Wu of Columbia Law School observed, American Airlines, which has become known for lousy customer service and lousier (if possible) labor relations, began raking in the bucks after completing its merger with US Airways in 2013.

“There are plenty of things American could have done with all that money,” Wu writes. “It could have stored up its cash reserves for a future crisis. ... It might have tried to decisively settle its continuing contract disputes with pilots, flight attendants and mechanics.” Instead, from 2014 through 2020, American spent $15 billion buying back its own stock.

To be fair, there can be sound justifications for share buybacks. Corporate executives sometimes can make the case that no other investment yields as much potential return as buying up their own undervalued shares.

But given the relentless neglect of middle-class employees by big employers, buybacks have done little except exacerbate economic inequality. Companies are always faced with the choice of investing in their workers or their shareholders; almost universally over the last few decades, they’ve chosen the latter.

And now they want taxpayers to keep them afloat. Sure. That’s a worthy goal. But the public, through its political leaders, has unprecedented leverage over corporate America in this crisis. Let’s use it.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.