‘The $2 is insulting’: Retail workers fight for more pay amid coronavirus crisis

- Share via

Work has changed for Daniel Reyes-Velarde, an employee at a CVS in Lakewood.

Lines are longer than ever, leaving him little time to restock the shelves and label items. Hand-washing is mandated, timed, and sometimes overseen by a manager. Customers are panicked, and every conversation feels like an added risk.

For the record:

9:39 a.m. April 5, 2020An earlier version of this article attributed a quote during a conference call to Senior Vice President Mark Champagne. Champagne no longer works at the company. The comment was made by a 99 Cents Only Store executive.

“I get nervous talking to so many strangers on a daily basis,” Reyes-Velarde said. “I just have my guard up — try not to touch my face during my shift.”

As Californians hunker down per state and local “stay at home” orders to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus, many retail workers continue to report to their jobs — assuming personal risk to perform roles now seen as vital to public health and maintaining a sense of normalcy.

This has given these low-wage workers new visibility and leverage.

A cascade of major chains including Target, Walmart, Whole Foods, Costco, Sprouts and Kroger have offered bonuses or temporary raises to employees working during the pandemic. Safeway boosted wages by $2 per hour, and several independent grocers offered raises of up to $6 or $7 per hour, according to United Food and Commercial Workers, a national union representing grocery and other retail workers.

The latest updates from our reporters in California and around the world

CVS is providing bonuses of $150 to $500 on a sliding scale to on-site staff, including pharmacists, managers and hourly employees like Reyes-Velarde, according to an informational packet shown to employees and reviewed by The Times.

The extra pay is an incentive for those doing increasingly difficult and dangerous jobs — and a recruitment tool as retailers face staff shortages as workers call in sick or take time off. But it’s not necessarily enough to quell workers’ frustration or stave off very real concerns about safety.

Reyes-Velarde said the one-time bonus CVS offered was “pretty wack.” Workers, he said, should be paid one and a half times hourly pay for the risk — even a $2-an-hour raise would be better than the $150 he will receive if he continues to work until the bonus is paid out in May.

CVS did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Even with safety precautions implemented by retailers, including limiting the number of shoppers in a store at any given time and assigning staff to cleaning shifts, health concerns remain.

“All of us have resigned ourselves to the fact that we’re probably going to catch it at some point,” said Colton Woods, 27, who works in the electronics department at a Target in Van Nuys.

Retail workers fret about whether they’re allowed to wear protective masks and gloves, receiving contradictory messages from managers and corporate headquarters. Even if their employer has offered paid leave for those who test positive for the coronavirus, some worry they won’t be able to access the time off in the event they get sick, because tests are so difficult to come by. Some wonder if it’s safe to touch cash and whether a few feet of counter space is enough of a buffer.

These concerns, along with consumer-facing workers’ newfound visibility, have sparked protests at some companies. Grocery delivery start-up Instacart held a strike on Monday calling for higher pay and better access to disinfectant and paid leave.

A group of Whole Foods employees across the country called in sick Tuesday in an effort to press the Amazon.com-owned grocery chain to provide more protections and pay. The company announced a temporary $2 hourly pay increase March 16.

Organizers of the sick-out are calling for that raise to become permanent, hazard pay of double the current hourly wage, paid leave for all workers who self-quarantine, more sanitation supplies, and free coronavirus testing. If a worker tests positive, they want the store where the employee works to be closed immediately and remain closed while all employees at that location are tested.

Several Whole Foods employees have already tested positive, including one at a store in Huntington Beach. Daniel Steinbrook, 30, an employee at a Whole Foods in Cambridge, Mass., said he worries it’s only a matter of time before a worker succumbs to the disease.

“The $2 is insulting, to be honest, it’s not nearly enough,” he said. “Compensation should reflect that risk.”

Samzari Sekyi-Williams, an employee at a Whole Foods in Morristown, N.J., said he was repeatedly told by store management and a regional human resources office he could not wear a mask without a doctor’s note.

On a March 24 call, which Sekyi-Williams said he was recording, he asked why he hadn’t been allowed to wear a mask. A Whole Foods HR representative said “you were advised because we were following CDC protocol.” Centers for Disease Control guidelines do not explicitly recommend masks for nonmedical personnel.

“We don’t want to cause any scare in that matter for the customers,” the HR representative said.

Workers at several retailers described similar difficulty attempting to wear or secure personal protective equipment.

The HR representative told Sekyi-Williams it would now be acceptable for him to wear a mask. But by then, he had already called off work — and he’s not sure if he’ll return. “It’s left a sour taste in my mouth,” he said. “They’re not taking safety seriously.”

Beginning Friday, San Diego County is requiring grocery workers and other employees who regularly interact with the public to wear face coverings. Officials in Los Angeles, Riverside County and the Bay Area have urged residents to wear face covering when out doing essential business.

A Whole Foods Market spokesperson told The Times any team member who wishes to wear a mask while working may do so. The spokesperson said the company has not seen an operational impact from the sick-out and has rolled out a number of safety measures including additional cleaning, crowd control and daily temperature screenings for Whole Foods employees and Prime Now shoppers.

“It is disappointing that a small but vocal group, many of whom are not employed by Whole Foods Market, have been given a platform to inaccurately portray the collective voice of our 95,000+ Team Members who are heroically showing up every day to provide our communities with an essential service,” the spokesperson said.

As grocery and retail workers push for better conditions, their ranks are growing. Millions of Americans are losing jobs at restaurants, hotels and airlines as businesses large and small go on hiatus. But grocers, pharmacies and retail giants are on hiring sprees as demand for essential goods and food has skyrocketed.

Walmart plans to add 150,000 staffers to warehouses and stores, speeding up its hiring process to get people into new jobs within 24 hours. Dollar General is looking to add up to 50,000 employees to its workforce by the end of April., while Albertsons wants to hire 30,000.

The program had worked with labs in Wuhan, China, and around the world to detect deadly viruses that could jump from animals to humans.

“Companies are simply having a hard time getting people to work and they do what economics tells us should happen, which is, as employers become more desperate for workers, they’re willing to pay more,” said Catherine Fisk, a UC Berkeley labor law professor.

Not all added compensation is the same, in nomenclature or substance. While workers and unions see it as compensation for working in hazardous conditions, Starbucks calls its $3-an-hour increase for employees who continue working “appreciation pay.” Sprouts calls the bonuses it rolled out “hero pay.”

Bonuses are less costly for employers than temporary pay raises, which are in turn less costly than wage increases, said economist Ken Jacobs, chairman of UC Berkeley’s Labor Center. Awarding hazard pay in the form of a bonus makes it easier for companies to return to normal pay when the crisis is over, because with a one-time bonus there isn’t an expectation that will continue, Jacobs said.

Public health experts warn that better compensation does not remove the legal responsibility for employers to create a safe workplace.

As shoppers crowd stores and empty shelves of toilet paper, big retailers have rolled out safety measures to minimize the potential spread of the virus among customers and employees. Target, for example, said it is cleaning carts after each use and installing Plexiglas partitions at cash registers. Walmart said on Tuesday it would begin taking employees’ temperatures as they report to work.

Lauren Cutrer, an employee at a Trader Joe’s in Palms, said measures the store implemented — including adjusting open hours and limiting the number of shoppers at one time — have put a damper on some of the chaos and helped prevent burnout. And it helps that she and her co-workers are allowed to do their shopping before the store opens to customers.

The county confirmed 13 new coronavirus-related deaths Thursday, bringing the toll to 78. The number of cases in the state swelled to more than 11,000.

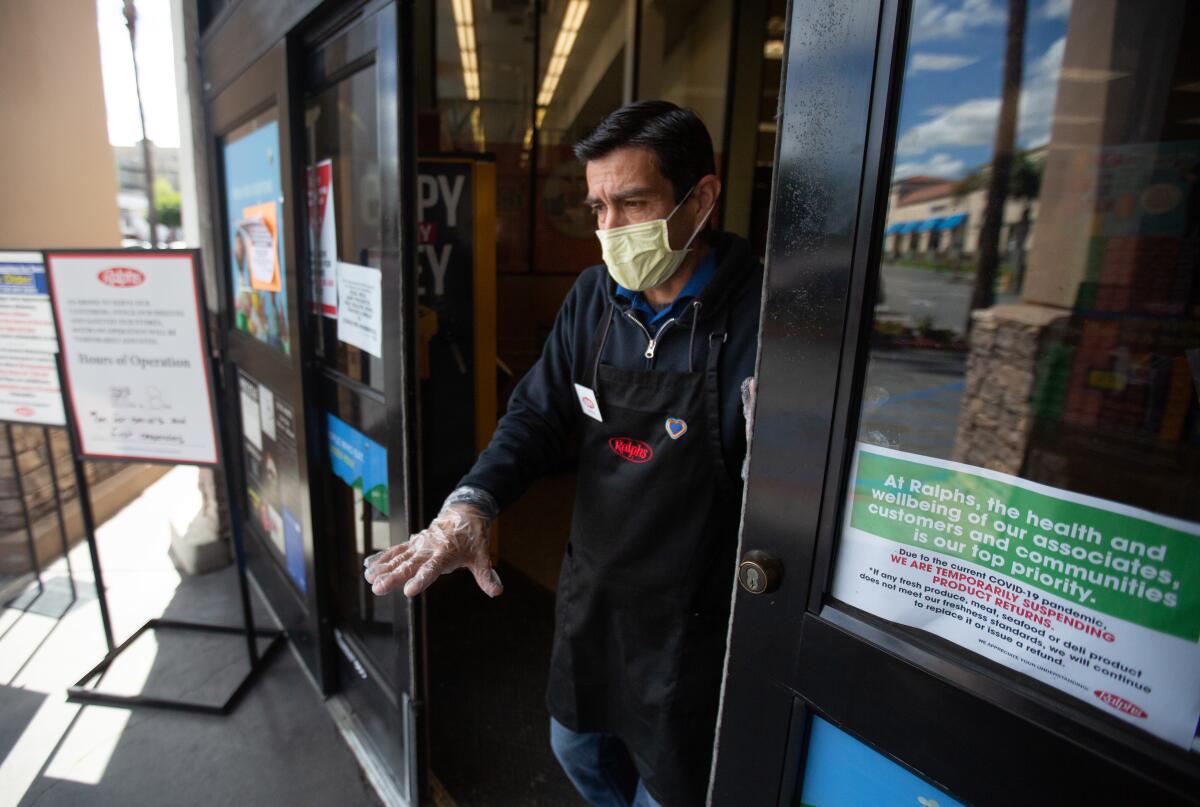

Employees worried about getting sick quickly developed an urgent set of concerns, and have pushed companies to respond and adapt or clarify policies. Ralphs grocery workers represented by UFCW plan to rally Friday to demand the company provide face masks, after L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti on Wednesday urged residents to wear face coverings.

California’s Injury and Illness Prevention Program requires that employers develop a plan that identifies hazards and implement prescribed safety measures. Theoretically, retail workers should be able to request a copy of a plan that includes coronavirus-related measures, said Laura Stock, executive director of the UC Berkeley Labor Occupational Health Program.

But it’s clear there are limits on how far greater visibility and public dependence on low-wage workers will carry them. Not all complaints are leading to improved work conditions.

Ahead of a conference call scheduled for executives at the 99 Cents Only Store to address operations during the pandemic, district leaders of the chain headquartered in the city of Commerce collected staff questions via email from managers. In came a flood of repeated queries in an email chain.

“Will we be getting any hazard pay or increases?” one manager asked.

“I had the same question about hazard pay.”

“My store is asking about hazard pay as well,” wrote another.

When company executives clarified on the March 25 call that the company would not be offering hazard pay, an employee pushed back.

“We put our neck on the line,” he said. “How are we to take care of our associates if we’re not letting them know in essence we do care by rewarding them with pay they’re seeing other essential stores do?”

A 99 Cents Store Only executive who identified himself as “Mark” on the call said panic about the risks had been blown out of proportion, and that the retailer did not have the resources of bigger companies to provide hazard pay.

“I think it’s important to know that while we’re a large enterprise, we’re not the Walmarts and the Targets and the Amazons of the world. So for us, we’ve had to remain very nimble,” he said, according to a recording of the conference call reviewed by The Times.

Jason Kidd, president and chief operating officer of 99 Cents Only Stores, said the company is following CDC guidance and has empowered managers to limit in-store customers as needed. “We are evaluating different types of appreciation reward programs for our associates,” he said in a statement.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.