Column: The COVID-19 pandemic shows that it’s time for a new New Deal. Here’s a blueprint

- Share via

No one who follows economic affairs could miss the signals that the U.S. economy has long been built on a foundation of quicksand.

Income and wealth inequality has been soaring as rank-and-file workers have lost the power to organize for workplace rights and corporations increasingly have funneled profits to shareholders.

The biggest financial bailout of recent years, the tax cut enacted by Republicans in December 2017, went almost entirely to corporations and the wealthy. The working class got crumbs.

Regardless of COVID, the economy has been working best for the wealthy and white Americans.

— Julie Margetta Morgan, Roosevelt Institute

The federal minimum wage, which would be $24 an hour had it kept pace with worker productivity since the 1970s, is mired at $7.25.

Even states and localities that have been in the forefront of the living wage movement tend to aim at a target of only about $15. Women and Black workers bear the brunt of these inequalities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the fragility of the American system. The working class, especially Black and Latino workers, are becoming sickened and dying at higher rates than whites. In part that’s because they’re overrepresented among “essential” workers or those with few options to work from home.

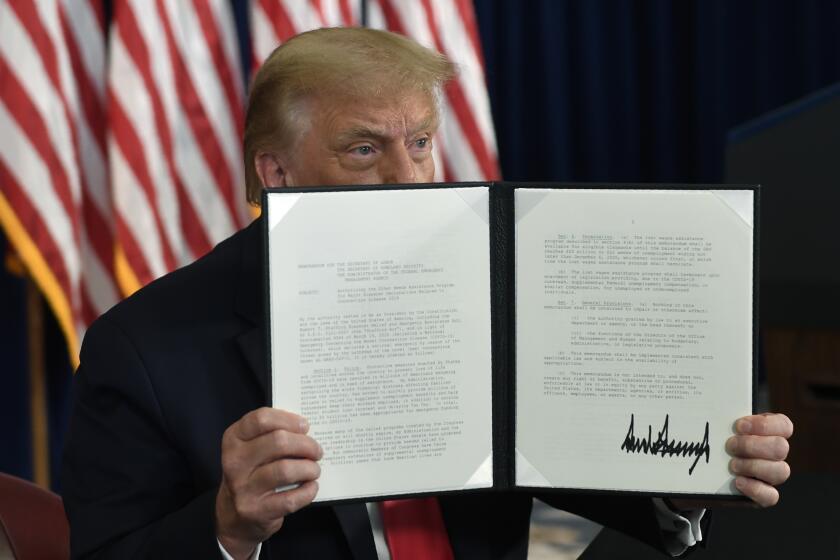

Even the pandemic relief measures undertaken in Washington have favored the rich. The Federal Reserve’s backstopping of securities trades serves the investor class, and congressional subsidies provided billions to business owners. But Republicans in Congress have blocked the extension of enhanced unemployment benefits for the working class that expired last month.

FDR’s New Deal aimed not to stimulate the economy, but protect families from hardship.

Plainly, America is ready for a reset of its economic principles akin to what happened after the last great economic crisis, the Great Depression. That crisis produced the New Deal.

This one has produced a blueprint for the next New Deal. It comes from the Roosevelt Institute, a think tank affiliated with the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, and is titled “A True New Deal: Building an Inclusive Economy in the COVID-19 Era.”

“We think the New Deal provides inspiration and in some ways a model for what ought to be done now, particularly in terms of the mix of immediate relief for families and structural changes to the ways our economy and society operate,” says Julie Margetta Morgan, the institute’s vice president for research and the organizer of the report.

The report outlines several “essential policies.” These include cancellation of student, housing and medical debt; creation of a federal jobs guarantee and universal childcare guarantees; the federalization and expansion of unemployment coverage; strengthening of collective bargaining rights; and re-invigoration of antitrust enforcement to produce “real trust-busting.”

The program would bring about reforms relevant to the lives of the working class and minorities, not merely produce short-term relief to families affected by the pandemic.

What’s most interesting about the proposals is that they try to address the manifest flaws in the New Deal as a model. “You can’t look at the New Deal without seeing how it failed to change power structures in many key ways and actually reinforced the powerlessness of people of color and women,” Morgan told me.

Especially at first, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal was a halting, ad hoc effort. It reflected an outlook FDR had expressed in a speech at Georgia’s Oglethorpe University in May 1932, effectively kicking off his presidential campaign.

In recent days, alarm about the economic impact of the novel coronavirus have turned conservatives who weeks ago were boasting about the shrinking of the U.S. government into raving Keynesians, proclaiming the virtues of deficit-financed economic stimulus.

In that speech, he promised “bold, persistent experimentation” and continued: “It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

In the New Deal, Roosevelt tried plenty and discarded plenty. He shut down the entire banking system to give it time to respond to the dire financial crisis of early 1933. He sharply cut the federal payroll (then restored much of the cutback under political pressure). He imposed strict regimentation on industry, which failed, and on agriculture, which sort of worked until the Supreme Court overturned it.

He created a jobs program that built parks and playgrounds, another that built airports and school buildings, and a third that unapologetically paid for “make-work” jobs just to keep Americans fed, clothed and housed. He imposed disclosure rules on stock issuers, turned the Federal Reserve into a functional monetary regulator and created Social Security.

The breadth of FDR’s pledge — and let’s be candid, its vagueness — showed that he and his brain trust had no historical model to guide them. As a result, though some of its individual elements became landmarks of progressive policy, its general approach to social change was more conservative. The treatment of Black workers and families is a good example.

Unemployed Black workers faced stringent quotas on New Deal work relief programs, and those who obtained jobs were shortchanged in wages by New Deal pay policies. Black families consistently were barred from New Deal residential communities, some of which were built on land from which they had been evicted.

New Deal programs crafted in Washington were turned over to local administrators, who flagrantly discriminated against Black workers, especially in the South; in Mississippi, where Black residents were 50% of the population, only 46 Black youths were admitted into the government’s first jobs program, the Civilian Conservation Corps, where they comprised 1.7% of the recruits.

Even Social Security at first excluded farm and domestic workers, trades that employed 65% of Black workers. Domestic workers wouldn’t be added to the Social Security rolls until 1950, and farm workers not until 1954.

A Senate committee votes to confirm Federal Reserve Board candidate Judy Shelton, a crank about the gold standard.

The Roosevelt Institute blueprint is determinedly inclusive. Rather than merely augment means-tested subsidies for low-income college students, which allow the inequities of the existing educational system to be perpetuated (and generally fail to cover student living expenses, an obstacle to low-income families), the institute calls for funding tuition-free public institutions.

That means shoring up the funding for community colleges, the entry point into higher education for a large percentage of low-income and minority students. “Community colleges are often the ones whose funding is the first to get cut and are expected to do more with less,” Morgan observes, “even though they educate a broader swath of the population.”

A federal jobs guarantee would offer federal funds to state and local governments for jobs that would provide a minimum salary and benefits, as well as unionization rights and the right of workers to sue over alleged discrimination.

As the institute notes, a guaranteed jobs program would “offer a clear entry point to the labor market for those who have struggled to reenter, like formerly incarcerated people” and disabled people. Moreover, by guaranteeing wages and benefits and eliminating the prospect of unemployment, it would give workers more bargaining power in the private employment market.

Trump’s payroll tax deferral is a mortal threat to Social Security.

Perhaps most important in the current context, it would help bring about the “mass mobilization necessary to serve our country’s larger economic and social needs,” such as coronavirus testers and contact tracers, and construction workers to rebuild public buildings to be energy-efficient.

There may be no better moment in recent history for this broad rethinking of the American economy. As Greg Sargent of the Washington Post observes, the current crisis provides an opening for Joe Biden, should he win election in November, to act boldly, for market rules “that we created and that we can change” are at the heart of the inequities in our economic system.

“Regardless of COVID,” Morgan says, “the economy has been working best for the wealthy and white Americans. Pre-pandemic, we were in the midst of a crisis of worker power. Right now, employers hold all the power about whether and how employees come back to work across the economy.”

We may be at a historic inflection point. “What gives us hope is that the protests we’ve seen over the last several months have had a cross-racial and cross-income solidarity that are at the core of progressive policy-making,” Morgan says. The challenge for progressive policy members will be to craft policies that both address immediate needs and ensure that we emerge from the pandemic crisis with “a stronger, more inclusive economy.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.