Column: There’s a model for healthcare reform. It’s called Amazon.com

- Share via

We can all probably agree that Amazon, more so than any other company, has trained us to be savvy online shoppers. It allows for effective comparison shopping and a clear sense of costs prior to making a purchase.

So why don’t we make similar tools available to medical consumers?

And why don’t we require healthcare providers to compete for our business the same way Amazon makes retailers and manufacturers go toe to toe on price and quality?

“That would change things dramatically,” said Stephen T. Parente, a health economist at the University of Minnesota. “It would make our healthcare system much more rational.”

As he spoke with me, his dog started barking as Amazon delivered a package to his door.

“See?” Parente joked. “The system is working.”

The notion of Amazonifying healthcare arose as we discussed a survey released this week showing that the vast majority of respondents — 83% — “want to see accurate information on out-of-pocket costs before having healthcare services.”

A customer thought she was responding to a Chase fraud warning. She was actually in touch with a con artist making a play for more than $10,000.

The survey of more than 1,000 people also found that a quarter of respondents “have avoided getting care because they did not have information about the costs.”

This is just a small corner of the wildly dysfunctional, utterly consumer-unfriendly U.S. healthcare market, into which Americans pump about $4 trillion a year.

Fixing the largely for-profit U.S. healthcare system is a massive undertaking, which is probably why few politicians have the stomach to try, and why many adopt knee-jerk opposition to any proposal for meaningful change.

But this new survey from HealthSparq, an Oregon provider of technology for health insurers, shines a light on one aspect of healthcare that is fixable, or at the very least could be handled much more openly and transparently.

Pricing.

A Southern California fitness company called Pure Barre charges job applicants $1,800 for their training. That may be illegal under California law.

“People are eager for pricing information in healthcare and it’s an area that creates so much frustration,” said Mark Menton, HealthSparq’s general manager.

The survey results, he said, make clear that what healthcare consumers want “is personalized information and guidance.”

Which is, of course, exactly what makes Amazon so powerful and successful.

Amazon’s platform learns from your decisions and behavior. It recommends things you may not have considered. It bends over backward to make your shopping experience as hassle-free as possible.

No less important, Amazon presents all your costs — list price, taxes, shipping — automatically and seamlessly, and applies any discounts you may be eligible for. If you have an Amazon credit card, it manages your reward points as well.

Say what you will about Amazon’s market power, questionable treatment of workers and annoying commitment to upselling you at every turn. The company revolutionized online shopping and turned a once-perilous experience into a smooth and convenient one.

As Parente and I kicked around ideas, we agreed that it would be infinitely better if healthcare consumers could see all their costs presented upfront as easily as Amazon does it.

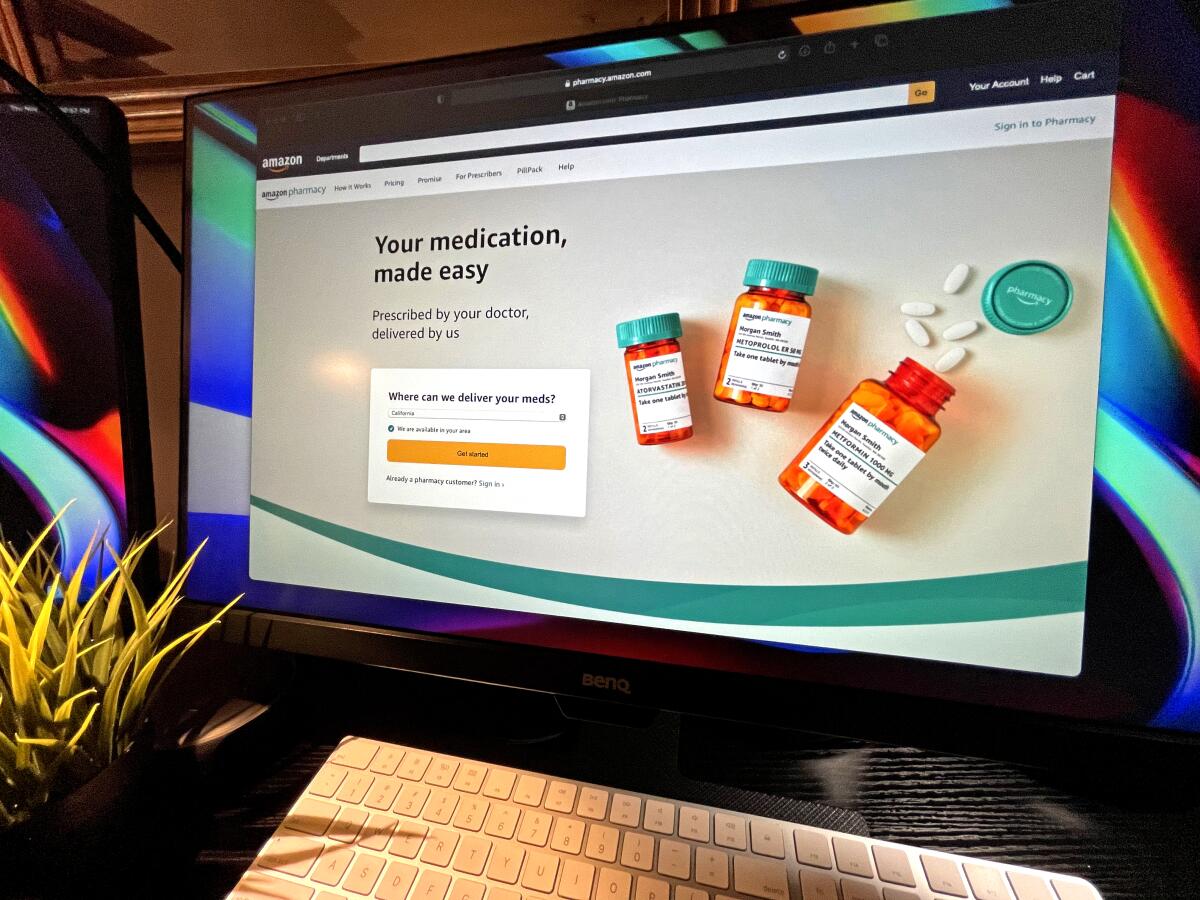

Amazon Care, now being tested on company employees, includes video conferences with doctors and nurses, online prescriptions being written and drugs being delivered by courier.

For instance, if you’re shopping for an elective procedure such as a hip replacement, there’s no reason an Amazon-like hospital platform couldn’t give preliminary figures for the cost of the surgeon, anesthesiologist and operating room, not to mention supplies and administrative fees.

Parente and I also liked the idea of a LendingTree-type model that, instead of featuring mortgage companies, would aggregate competing healthcare quotes from different providers.

Why should patients do all the heavy lifting? Why not create a system in which doctors and hospitals are trying to win our business with the best possible service at the lowest possible price?

I spoke with a number of healthcare experts. Not all agreed that greater price transparency would change the equation in a significant way.

“Americans don’t want more information on how overpriced and inaccessible the healthcare services in their communities are,” said James Robinson, a professor of health policy and management at UC Berkeley. “They want reasonably priced and accessible services.”

Yeah, but wouldn’t it be cool if we could shop for medical treatment as painlessly as we shop for goodies on Amazon?

“Don’t get me wrong,” Robinson replied. “I am not opposed to price transparency any more than I am opposed to motherhood. The question is: Is the juice worth the squeeze?”

By which he meant that the Amazonification of healthcare shopping could distract from the more important job of actually lowering costs.

A SoCal man sought mental health treatment during the pandemic. He couldn’t find a single suitable therapist within his insurer’s network.

David C. Grabowski, a professor of healthcare policy at Harvard Medical School, said most Americans are unaccustomed to the idea of shopping around for treatment.

To make people more comfortable with this idea, he said, “we need to simplify the information that patients are provided. The goal is to shift patients from high-cost providers to low-cost providers.”

He proposed requiring higher co-payments for higher-cost healthcare providers, which would send a market signal that shopping around can have benefits.

As for Amazonifying the medical shopping experience, Grabowski agreed that “patients should be provided price information prior to any care being delivered.”

In fact, new federal rules require hospitals to post prices online for some of their services. The intent is to reduce so-called bill shock resulting from unexpected charges.

But Glenn Melnick, a health economist at USC, said the rules are “quite weak” and may be ignored by some medical providers. “I expect many hospitals will just pay the fine if it is enforced,” he said.

Ultimately, the HealthSparq survey makes clear that patients are too often in the dark about pricing and that this is affecting public health.

The fact that 25% of respondents said they’d skip treatment because they don’t know how much it costs should be a wake-up call for policymakers.

“The healthcare industry has made people terrified of incurring crushing out-of-pocket costs,” said Miriam Laugesen, an associate professor of health policy and management at Columbia University.

“People are going to shy away from having care when they have no idea what kind of bill they are going to face a month or two months down the road,” she told me.

Amazon has already figured this out. The company knows if it makes shopping for, well, anything as easy and straightforward as possible, more people will buy more stuff.

The healthcare industry should pay attention to that insight. Amazon is a volume business, more interested in long-term customer loyalty than scoring a quick sale.

Healthcare providers focus almost exclusively on the quick score, with little regard for whether a patient feels he or she was treated fairly.

They have much to learn.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.