Column: A new law aims to protect you from surprise (read: bonkers) medical bills

- Share via

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau warned debt collectors and credit agencies last week that they need to step more carefully when it comes to trashing people’s credit scores because of stratospheric medical bills.

The agency’s notice underlines that the federal No Surprises Act took effect this month, protecting people from many unexpected healthcare charges.

“Too many Americans have been shocked by surprise medical bills and forced to pay up through credit report coercion,” said CFPB Director Rohit Chopra.

What he means by “credit report coercion” is healthcare providers threatening to let debt collectors hold patients’ credit scores hostage unless they pay even the most wildly inflated medical bill.

“Our action today should serve as a reminder not to collect on or furnish credit reporting information about invalid medical debt,” Chopra said.

This is an important safeguard. A 2019 study found that medical bills were a primary factor in about two-thirds of U.S. personal bankruptcy filings. More than half a million U.S. families go bankrupt annually because they can’t afford healthcare.

But the new law won’t help people already feeling the squeeze from unpaid medical bills.

People such as Mei Li.

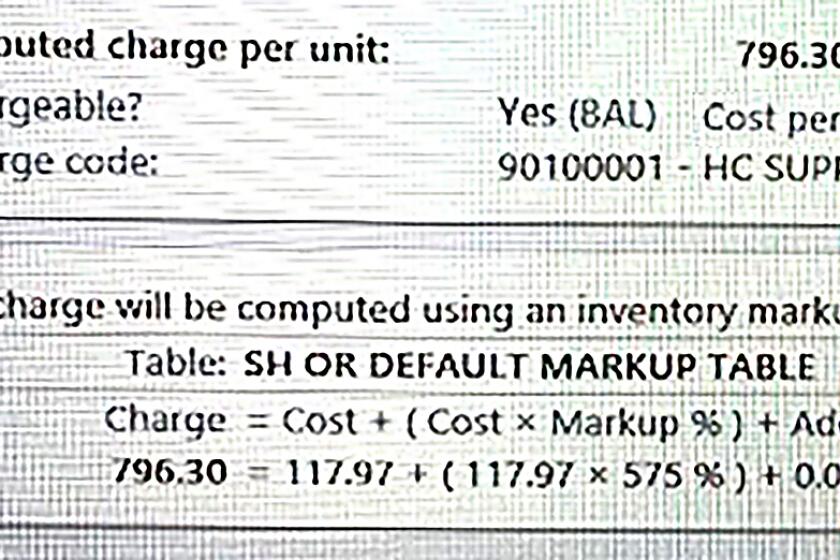

Screenshots of a system used by Scripps Memorial Hospital show markups of as much as 675% being imposed automatically during treatment.

The Connecticut resident contacted me the other day seeking help with nearly $4,000 in charges for a pair of stitches.

Li, an animator and illustrator for children’s books, is uninsured. She told me she had to choose between health coverage and trying to build her own company.

While that’s not a choice anyone should have to make, 35-year-old Li gambled that because she’s relatively young and healthy, she could invest in her business rather than seek coverage through the Affordable Care Act.

She gambled wrong.

In August, Li slipped and fell while out with her boyfriend. The cut on her chin wasn’t too serious, but it was clear she’d need stitches to close it.

“Unfortunately, all the urgent care clinics were closed,” Li told me. “So I had to go to the emergency room at Norwalk Hospital.”

She said she explained in advance that she was uninsured and asked for an estimate of how much her treatment might cost. No one at the hospital would offer a figure, she said.

After waiting several hours to see a doctor, Li said, she was finally ushered into an exam room and given an anesthetic, two stiches and a bandage. That’s it. The entire procedure took less than half an hour.

The first bill was for $3,197.02.

It included a $405 charge for the ER doctor, a $193 charge for “emergency department,” a second $663 charge for the ER doctor (she saw only one), a $100.02 charge for “pharmacy” (probably the shot and stitches), plus three additional (and mysterious) charges for “emergency department” that totaled $1,836.

Li was billed $689 more for returning a few days later to have the two stitches removed.

USC researchers found that middlemen are pocketing a growing share of revenue from insulin sales -- another sign of the drug market’s inefficiency.

These charges were reminiscent of my recent column about how an electronic health record system at Scripps Memorial Hospital in Encinitas automatically imposes price hikes of as much as 675% to routine medical charges.

Documents leaked to me by a former nurse at the hospital showed stitches that cost just $19.30 were automatically marked up to $149.58.

It’s important to stipulate that, if they can, people should pay their medical bills. Even if you feel you’re being ripped off, you’ll only make matters worse by ignoring payment-due notices.

Let’s reiterate, however, that it’s completely intolerable for residents of the richest, most powerful country in the world to have to choose between a livelihood (or paying the rent, or putting food on the table) and receiving healthcare.

“I decided to wait and see if my business would pick up before I paid the bills,” Li said.

The hospital had other ideas. After several months had passed, it handed Li’s outstanding bills to a debt collector.

She said she’s been scrambling ever since to address the situation but can’t get anyone on the phone to help her.

“Every time I called, the line was either busy or I had to leave a message,” Li said. “Then they never called back.”

So she reached out to me, and I contacted Norwalk Hospital’s parent company, Nuvance Health.

Amy Forni, a Nuvance spokesperson, declined to discuss details of Li’s bill. She emphasized, however, that Norwalk Hospital, like nearly all medical facilities, charges patients not just for treatment but also for the cost of maintaining healthcare resources and treating anyone who seeks emergency care.

“Emergency departments are equipped with resources and highly trained staff to identify, diagnose and treat serious medical emergencies,” she told me. “For these reasons, emergency departments are a more expensive place for care, compared to primary care offices or urgent care clinics.”

All true. Yet for uninsured people like Li, the ER is often the only choice available.

In California, you can’t be sued for consumer debt older than four years. But making even a partial payment can restart the debt clock.

“In most cases, we can estimate the cost of care for planned medical procedures and treatments,” Forni said. “However, not for emergency services ... because staff need to triage patients before they know what care to provide and what it might cost.”

She said Norwalk, like most hospitals, will work with patients facing financial difficulties.

If such contingencies were sufficient, though, there’d be no need for debt collectors or other strong-arm tactics. The fact that medical bills drive so many people into bankruptcy shows that whatever financial assistance hospitals offer, it isn’t doing the trick.

According to the CFPB, 17% of U.S. adults “had major, unexpected medical expenses” in 2020, with the median bill running as much as $2,000. Nearly a quarter of Americans “went without medical care due to an inability to pay,” the agency said.

The No Surprises Act is intended to make the healthcare system less unfriendly.

Passed as part of a 2020 spending bill, the law makes it illegal for medical providers to slap patients with crazy charges for out-of-network care, particularly in situations where people have no choice but to seek emergency treatment.

It also requires that patients receive easy-to-understand notices of their rights and who they should contact in the event of problems.

It may cost as little as $100 to manufacture a hearing aid. The list price is typically in the thousands of dollars (and not covered by most insurance).

As a sop to medical providers, the law includes an arbitration provision — that is, you can’t sue over surprise bills but have to agree instead to arbitrate any disputes.

Researchers at USC and the Brookings Institution said an arbitration clause “was a key demand of provider groups, who likely hope that they will be able to extract higher prices via an arbitration process.”

Xavier Becerra, the health and human services secretary who previously served as California’s attorney general, said in a statement that the No Surprises Act “is the most critical consumer protection law since the Affordable Care Act.”

“We are taking patients out of the middle of the food fight between insurers and providers, and ensuring they aren’t met with eye-popping, bankruptcy-inducing medical bills,” he said. “This is the right thing to do.”

It is. It’s also yet another dysfunctional aspect of the profit-focused U.S. healthcare system that could be eliminated overnight with introduction of a “Medicare for all” approach that would make bills transparent, consistent and reasonable.

Li told me Norwalk Hospital has gotten in touch with her as a result of my outreach but hasn’t yet shown any flexibility with her outstanding bills. It still wants its pound of flesh.

My advice: Pay up. Get insured.

And support lawmakers who understand that our current healthcare system isn’t working.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.