Column: Serranus Hastings’ heirs say he’s the victim of cancel culture. History ties him to massacres of Native Americans

- Share via

America’s reconsideration of its racist past hasn’t always been painless. The reputations of long-honored individuals have been revised, their honors withdrawn, names struck from monuments — often in the heat of controversy.

But one would have to look far to find a pushback as absurd as the lawsuit filed by heirs of Serranus Clinton Hastings over California’s decision to take their forebear’s name off UC’s Hastings College of the Law, which he founded with a gift of $100,000 in 1878. The state Legislature pledged in turn that the school would bear the Hastings name “forever.”

The lawsuit, filed Tuesday in San Francisco state court chiefly by six great-great, great-great-great, and great-great-great-great-grandchildren of Hastings, asserts that the law signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom on Sept. 23 to change the school’s name to College of the Law, San Francisco, is the handiwork of “modern-day cancel-culturalists.” (The law also ends the practice of perpetually reserving one seat on the law school’s board for a Hastings descendant.)

Removal of the ‘Hastings’ name ... heaps scorn and punishment upon S.C. Hastings, his descendants, and ... upon all the tens of thousands of Hastings law graduates living and deceased.

— Hastings heirs’ complaint about renaming of UC Hastings School of the Law

The lawsuit says the five-year effort to take Hastings’ name off the law school was provoked by “a couple of poorly-sourced opinion pieces” alleging that Hastings “fomented and financed raids by State-run militia on Native Americans in the late 1850’s and early 1860’s.”

A couple of points about that: The opinion pieces weren’t “poorly-sourced,” but based on solid historical research, including contemporary documents in the California state archives.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Moreover, although the lawsuit says there is “no known evidence that S.C. Hastings desired, requested, or knowingly encouraged any atrocities against Native Americans,” the evidence suggests that he well knew what was being done in his name and in his interest as one of the largest landowners in the Mendocino Valley.

The lawsuit contends that “removal of the ‘Hastings’ name ... heaps scorn and punishment upon S.C. Hastings, his descendants, and indeed, by association, upon all the tens of thousands of Hastings law graduates living and deceased.”

It hints that the heirs might be owed a return of the $100,000 gift, with 144 years’ worth of interest, though it observes that the repayment would be due only if the law school has “cease[d] to exist.”

The heirs, anyway, acknowledge in their legal complaint that the name-change law “does not dissolve the College.” But they contend that changing the name violates the promise made by the Legislature in 1878.

Whether their lawsuit has merit is not for us to say, if only because, in the words of Dickens’ Mr. Bumble, “the law is a ass.” That said, the law tends to frown on perpetuities as well as on legislative acts that bind future legislatures, except through constitutions. So a promise made in 1878 may have little weight in 2022.

As for whether the reputation of tens of thousands of Hastings alumni (who include Vice President Kamala Harris) is besmirched by taking Hastings’ name off their law school, or whether their reputation is enhanced by not being associated with the man, it’s a cute argument.

Having traveled the difficult road of coming to terms with racism in its own past, Caltech on Friday said it would remove the names of Robert A. Millikan and five other important figures in its history from campus.

But no such claim has been made on behalf of the graduates of Princeton University’s former Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, which removed Wilson’s name because of evidence of the former president’s racism, or graduates of Caltech, which has excised the once-revered name of Robert Millikan from its campus in recognition of his association with the racism-infused eugenics movement.

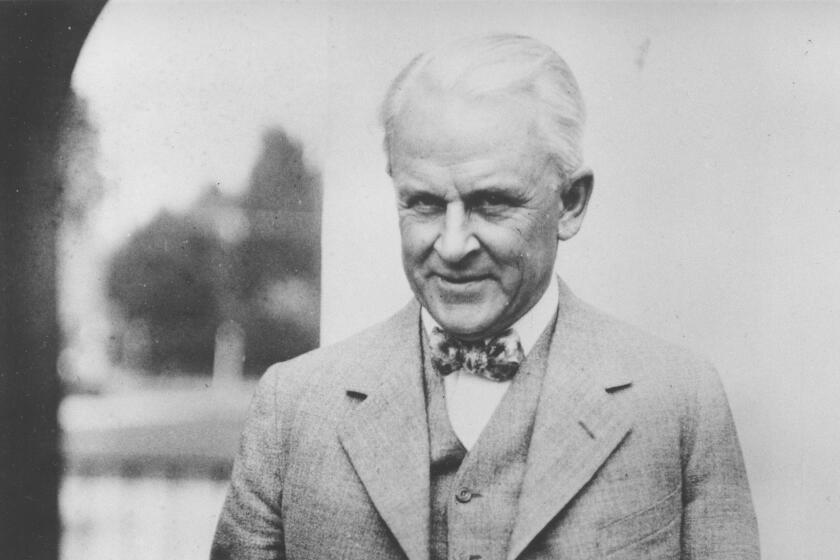

That brings us back to the story of Serranus C. Hastings, whose historical renown was based largely on his service as the first chief justice of the California Supreme Court.

A close examination of Hastings’ role in the genocide of Indigenous Californians in the 1860s and 1870s can be said to have started with a master’s thesis by Gary E. Garrett, a student at Cal State Sacramento, in 1969. Garrett mined the state archives to establish Hastings’ role in establishing and funding a local militia under Walter S. Jarboe, who as Garrett wrote “was well known for his hatred of Indians, an attitude that fitted him well for the work of Indian Killer.”

As UCLA historian Benjamin Madley reported in his encyclopedic 2016 book about the massacres, “An American Genocide,” Jarboe organized a group called the Eel River Rangers to hunt American Indians, promising them that Hastings — described by Madley as the operation’s “mastermind” — would pay their wages if the state government refused.

By August 1859, the rangers had conducted more than a dozen massacres of Yuki tribe members and others; a U.S. Army commander in the region reported to his superiors, “I believe it to be the Settled determination of many of the inhabitants to exterminate the Indians.”

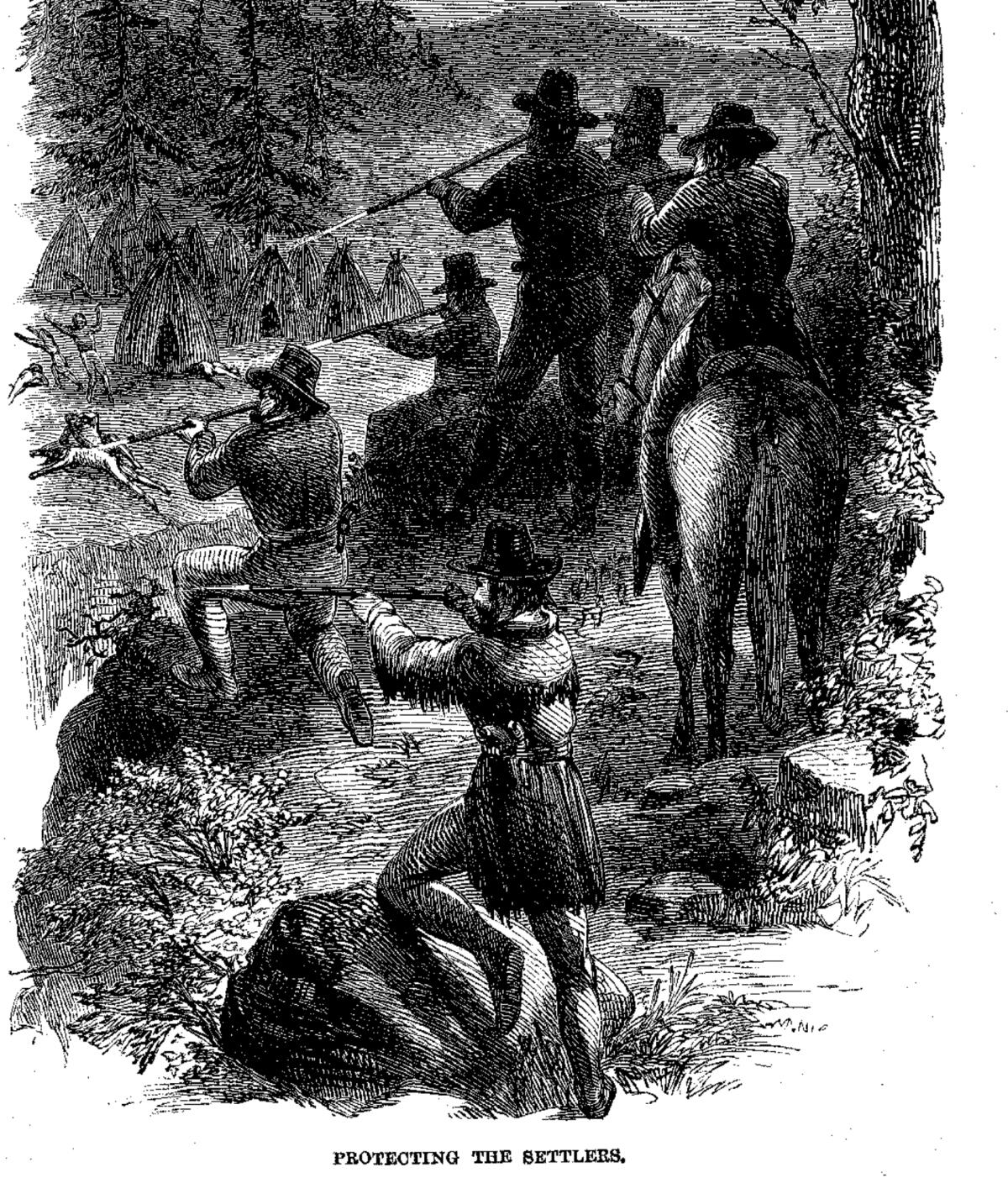

The context of this killing campaign is important. As white settlers moved into the California countryside for farming and ranching, they disrupted the lifestyle of the resident tribes.

John Wayne wasn’t a hero. He played one in the movies, not in real life.

According to a white paper commissioned from Brendan Lindsay, an expert on Native American history at Cal State Sacramento, by the law school’s Legacy Review Committee, the Yuki of the Mendocino region, accustomed to “forage for grass seeds, acorns, game and fish,” discovered “the grass eaten and the game driven off by large herds of cattle and horses ... and the path to rivers and streams blocked by white settlement.”

For sustenance, the tribes were forced to raid the settlers’ livestock, provoking punitive responses like the Jarboe raids.

The same thing happened throughout California. The reprisals by settlers and the U.S. Army were ferocious and uncompromising. “Let a tribe complain that the miners muddied their salmon-streams, or steal a few pack mules,” according to an 1877 government report, “and in twenty days there might not be a soul of them living.”

The Hasting heirs say in their lawsuit that despite an investigation by the California Legislature in 1860, “no charges were brought against the rangers for the atrocities .... Neither the committee, nor the California Legislature levied any accusations of malfeasance or impropriety against S.C. Hastings for these events.”

For historians of the era, these assertions can only look like some sort of a cynical gag. Almost no white people were ever charged in connection with the Native American massacres. They were presumed to be justified as retaliation for livestock thefts.

The California Constitution granted Indigenous people virtually no legal standing to object to their treatment by white people; they had no right of suffrage, and, while they had the right to bring complaints to a justice of the peace, no white person could be convicted of any offense “upon the testimony of an Indian.”

The contemporary writer J. Ross Browne, who served for a time as a federal Indian agent, would report of California’s tribes that “wherever they attempted to procure a subsistence, they were hunted down; ... shot down by the settlers upon the most frivolous pretexts; and the part taken by public men high in position, in wresting from them the very means of subsistence, is one of which any other than professional politicians would be ashamed.”

The Hastings heirs say their ancestor’s reputation has been sullied by “multiple layers of hearsay.” In fact, the documentary evidence is compelling.

Among the items in the state archives are a complaint by Hastings about “depredations” by local tribes and the failure of the Army to protect the settlers; an 1859 letter to then-Gov. John B. Weller pledging to provide arms for use by volunteer militia members; another letter to Weller stating that Jarboe needed more men; and a letter to Hastings from Jarboe detailing plans to attack a rancheria with 500 American Indians accused of stealing 200 horses.

There are depositions attesting to Hastings’ funding of Jarboe’s company and to a purchase order from Hastings for supplies for Jarboe. On the other hand, there is a deposition in which Hastings asserts that he knew nothing of any killings of Native Americans.

California settlers’ relations with Native American tribes constitute one of the blackest marks on the state’s history. For Hastings’ heirs to try to whitewash it as though he’s a victim of cancel culture through this ridiculous lawsuit is worth a horselaugh.

Unfortunately, a majority of the legacy committee empaneled by the law school concluded in 2020 that its name should stay. “Changing names may amount to falsely negating historical truths and legacies,” it asserted.

No other American institution of higher learning had “changed its name in response to revelations about its namesake,” the panel wrote. (Actually, a month before the committee published its report, Princeton had taken Wilson’s name off its public affairs school.)

The following year, however, the law school’s board approved changing the name. That could only be done by the Legislature, which now has acted, as it says, “to begin the healing process for the crimes of the past.” The Hastings heirs haven’t made the case that the process should cease.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.