Column: Moderna and Pfizer are jacking up the price of COVID vaccines. The government should stop them

- Share via

Stéphane Bancel, the chief executive of drug company Moderna, could barely restrain his pride in issuing his annual letter to shareholders on Jan. 3.

“Since the beginning, it has been our mission to deliver on the promise of mRNA technology for patients,” Bancel wrote, referring to the vaccines in the company’s product pipeline that use short pieces of genetic code to help cells build immunity.

“And we delivered at speed with our mRNA vaccine against COVID-19,” he continued. “As our first approved product, it has impacted hundreds of millions of lives around the world. ... We are harnessing the power of mRNA to create a new category of medicines and a company that maximizes its impact on human health.”

Moderna is committed to pricing that reflects the value that COVID-19 vaccines bring to patients, healthcare systems, and society.

— Moderna spokesman Christopher Ridley

A couple of pertinent points were missing from Bancel’s 2,700 words of self-congratulation. One was the contribution of the federal government to the company’s success.

That included a research grant of almost $1 billion from the government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, through 2020, plus a $1.5-billion federal purchase guarantee in 2020 for COVID vaccines before testing was even completed — a deal that materially reduced Moderna’s financial risks in developing the vaccine.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Nor does it count the millions, possibly billions, in federally funded basic research at academic institutions and government laboratories in mRNA technology — the foundation of the product developed by Moderna.

Also glossed over was Moderna’s intention to raise the price of its COVID vaccine from the estimated $20.69 per dose paid by the federal government through December 2022 (for 1.2 billion doses of COVID vaccines, including Moderna’s product and a similar mRNA formulation produced by Pfizer), to as much as $130 per dose.

Pfizer, which did not receive federal research funding but did obtain a government purchase guarantee, has also announced a price increase to as much as $130 per dose.

Pfizer’s vaccine also derives from basic government-funded research; indeed, on its website the company acknowledges the foundational work on mRNA technology by Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman of the University of Pennsylvania, research that was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

Thanks to the astounding success of its COVID-19 vaccine, Moderna is locked in a fierce battle with the U.S. government over who should get credit.

Both companies have justified the planned price hikes in part by citing the savings in healthcare costs the vaccines have produced.

In an email, a Pfizer spokesman told me that its vaccine and other therapies have “saved hundreds of thousands of lives [and] tens of billions of dollars in health care costs.” Pfizer “has priced the vaccine to ensure the price is consistent with the value delivered,” the email said.

Moderna makes a similar point. “Moderna is committed to pricing that reflects the value that COVID-19 vaccines bring to patients, healthcare systems, and society,” company spokesman Christopher Ridley said by email.

It’s impossible to overstate the moral depravity of this argument. The companies are saying, in essence, that they deserve a cut of the savings in lives and money attributable to their products, and they’ll decide the size of that cut for themselves — independent of considerations such as the cost of developing and manufacturing the drugs or the effect that higher prices will have on patients’ access.

No industry other than pharmaceuticals asserts that its prices should be based on the higher costs of alternatives, but it’s a familiar factor in drug pricing. Gilead Sciences, for instance, set the price of Sovaldi and Harvoni, its hepatitis C treatments, above $80,000 for a 12-week course based on the drugs’ “value premium” — the higher cost of alternative treatments.

After a U.S. Senate committee issued a blistering report about Gilead’s pricing strategy, the company stated that the drugs were “priced in line with the previous standards of care” and that the prices “are less than the cost of prior regimens, even though our therapies have significantly higher cure rates and very few side effects.”

The price increases of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines almost inevitably will translate into lower vaccination rates, even as executives at both vaccine companies assert that the price increases will be invisible to most Americans.

“Anyone with commercial or government insurance who is eligible to be vaccinated should be able to access the vaccine without any out-of-pocket payments,” Pfizer executive Angela Lukin told Wall Street analysts on a conference call Oct. 20, when the company announced its proposed list price of $110 to $130 per dose.

That’s highly misleading, however. Underinsured or uninsured Americans could be charged the full price, which would put the vaccine beyond their ability to pay. To the extent insurers or Medicare and Medicaid would shoulder most of the cost for their enrollees, it could be reflected in higher premiums.

Moderna’s founders are making a mint from COVID vaccines. But the company is failing its commitment to provide shots to the less wealthy nations.

Pfizer says that some uninsured Americans will be eligible for the company’s patient assistance program, which covers some co-pays for its drugs. But that program requires an application and considerable paperwork; it’s no substitute for walking into a pharmacy and receiving the shot on request, as has been possible through the government program.

Make no mistake: This is a public health issue. The government’s COVID vaccination program prevented more than 18.5 million excess hospitalizations and 3.2 million excess deaths, according to research by the Commonwealth Fund.

“Without vaccination, there would have been nearly 120 million more COVID-19 infections,” estimated the fund, which also calculated that the vaccination program “saved the U.S. $1.15 trillion ... in medical costs that would otherwise have been incurred.

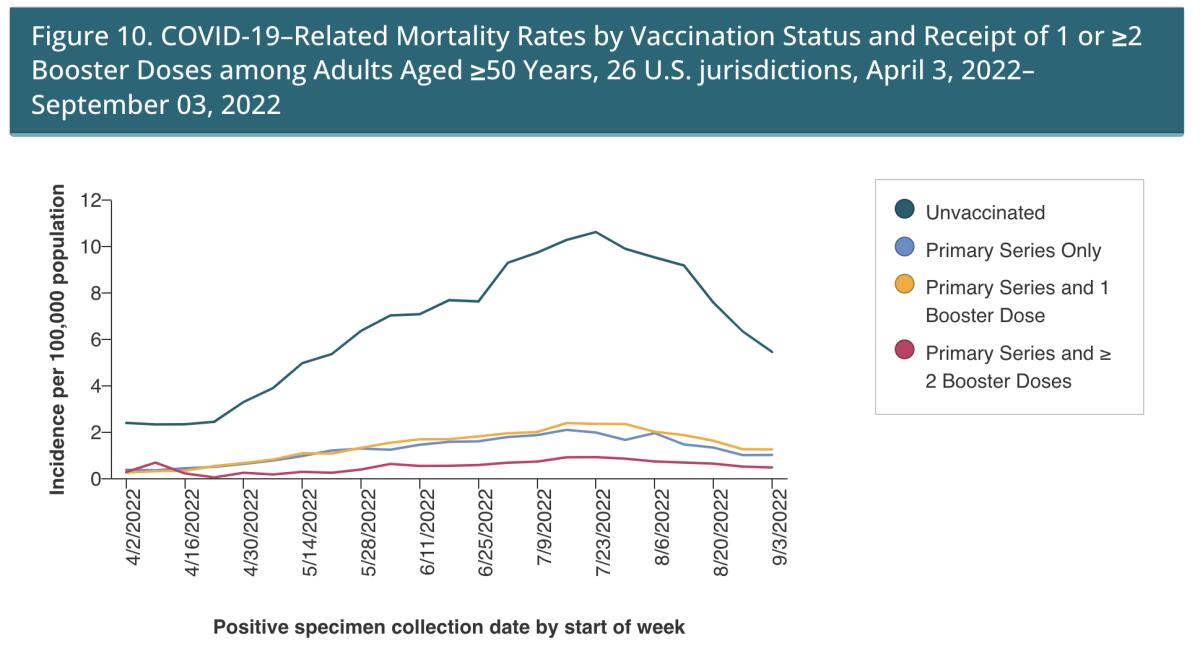

Government statistics plainly show that vaccinated individuals have a sharply reduced COVID-related mortality rate, with the gains multiplying for patients who are fully vaccinated and boosted.

Even though there’s no question that the vaccines have saved society money and lives, that leaves the question of how much in profits the manufacturers deserve to reap from them — as well as how to calculate the cost of reduced access to these products due to higher prices.

The list-price increases are only part of the story. The other side of the coin is the profit margin Moderna and Pfizer expect to see from the vaccines. According to an analysis by Oxfam, the mRNA vaccines could be produced for as little as $1.18 to $2.85 per dose, meaning that even at the government price the companies were collecting enormous profits.

There would appear to be plenty of headroom for Moderna and Pfizer to profit from the vaccines even at lower prices. Pfizer has projected annual sales of its vaccine at $34 billion and Moderna at $18 billion to $19 billion. Those estimates were based on 2022 sales, before price increases take effect. Government authorities have started to talk about a regime of annual COVID vaccine boosters, similar to flu vaccines, implying a steady stream of revenue for the companies for years to come.

The price increases reflect what Moderna and Pfizer both refer to as the transition to commercial marketing of the vaccines. That’s necessary because the federal government has run out of money to buy doses and distribute them for free. Last year, President Biden asked Congress for $3.9 billion “to help ensure ready access to vaccinations, testing, treatment and operational support” for Americans. He didn’t get it.

The effect of federal funding for Moderna has been stupendous — and a large proportion of that gain has flowed directly to shareholders. According to the company’s most recent quarterly report, the company spent $2.1 billion on research and development in the first nine months of 2022. But it spent $2.9 billion in the same period on stock buybacks, which pump up the value of its stock.

Religious exemptions to vaccinations have emerged as a dangerous and easily exploited loophole in public health policy. It’s time to ban them.

Those repurchases were part of $6 billion in stock buybacks authorized last year by the Moderna board, of which more than $3 billion remains available. Basic math tells you that had Moderna not received its more than $1 billion in R&D assistance from the government, it would have had at least that much less to upstream to shareholders.

As I’ve written before, it’s the cowardice of political leaders and government regulators that allows drug firms such as Moderna and Pfizer to dictate higher prices for products developed in part with government funding.

The government arguably has authority over pricing and distribution of products developed with federal funding, such as the COVID vaccines. The key factor is the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, which allowed private companies to commercialize inventions that grew out of federally funded research, but it reserved certain rights for the government to protect taxpayers’ investments.

Chief among them are “march-in rights.” These allow the government to require that a federally funded drug be licensed to other manufacturers, or to offer a license itself to alternative drugmakers to ensure that the drug is widely accessible. Those rights can be exercised if the government concludes that a manufacturer hasn’t taken sufficient steps to make a product publicly available or hasn’t brought it out on “terms that are reasonable.”

The government has never exercised its march-in rights, though it has occasionally threatened to do so to extract concessions from manufacturers. But as drug prices skyrocket, pressure on federal authorities to take action is intensifying.

Prostate cancer patients, for instance, have been pressing the Department of Health and Human Services to take action on Xtandi, a wonder drug for the disease that was developed at UCLA with substantial funding from the Pentagon and the National Institutes of Health.

The average wholesale price of Xtandi, for which Pfizer holds a manufacturing license, comes to $189,800 a year. (UCLA had collected more than $520 million in royalties from the drug when it sold the rights in 2016.) To date, Health and Human Services has failed even to hold a hearing on a year-old petition by prostate cancer patients aimed at bringing the drug price down by exercising march-in rights.

The COVID vaccines could be another test case. Few drugs on the market today can match their capacity to advance public health and few may be as sensitive to the level of price increases planned by Moderna and Pfizer.

This is a subject on which the federal government cannot and should not remain silent.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.