Column: 60 years ago in Los Angeles, piano virtuoso Glenn Gould revolutionized the music industry by ending his concert career

- Share via

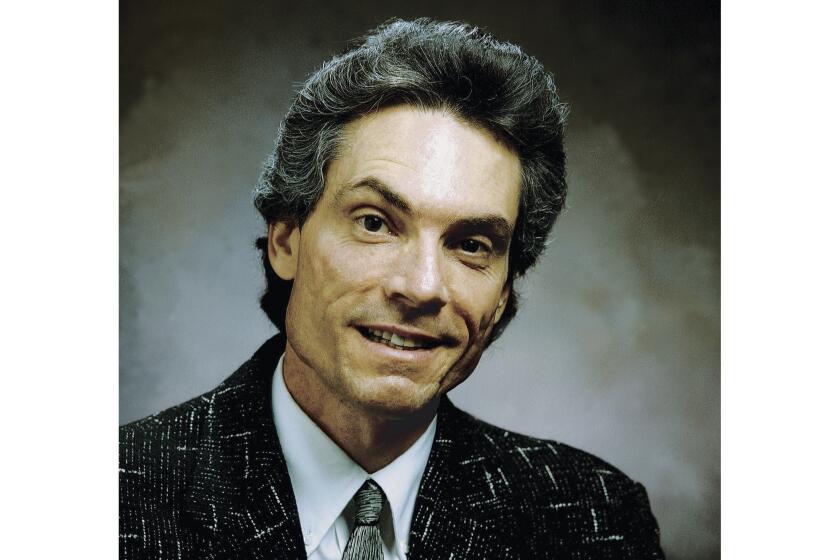

On the evening of April 10, 1964 — that is, 60 years ago Wednesday — the Canadian virtuoso Glenn Gould stepped away from the piano at the end of his concert at the Wilshire Ebell Theatre in Los Angeles and revolutionized the recording industry.

There was no announcement at that landmark moment in L.A.; only the ensuing circumstance would tell the story. For the Wilshire Ebell recital marked the end of the 31-year-old star’s performing career. He would never play another note in public.

He was the first — and possibly the only — classical musician to shun public performances entirely. Henceforth, his entire output would be heard only via records and videos.

Dial twiddling ... is an interpretive act.

— Glenn Gould grants listeners the right to manipulate recorded sound

Gould was then a world-famous exponent of the music of J.S. Bach. His debut recording on Columbia, released in 1956, was an electrifying performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, which had been consigned to academic obscurity.

The album was a monster hit and established Gould’s worldwide reputation. In a doleful irony, his digital rerecording of the piece, taken at a more stately tempo and with other changes, would be the last Gould album released by Columbia before his untimely death at age 50 in 1982.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

At the time Gould shifted to a recording-only career, his fellow artists doubted that he would stand by his decision. As late as 1971, Arthur Rubinstein told him, “You will come back to it, you know.” Gould replied, “If this is a bet, maestro, you will lose it.”

Gould demonstrated that recording technology need not come between artists and their listeners; in fact, it could enhance their relationship. His fans, of which I am one, find themselves in a uniquely intimate connection with the artist, in part because his astonishing technique and superb musical intelligence comes through so vividly in his recordings.

Gould in effect turned the economics of the music industry upside-down. Rather than seeing records as marketing adjuncts to concert tours, he showed that recordings could be the principal point of contact — in his case, the only point — between musicians and their fans.

Gould became the chief herald of the new era of digital recording, and of the power it gave artists — and audiences — to reconfigure even the most familiar classical warhorses to their individual tastes.

Chuck Philips, who died last month at 71, was the most important music industry journalist of his generation.

He foresaw that new technologies — including those not yet invented — could put creative decisions in listeners’ hands, allowing them to adjust the tempi and mixes of recorded pieces in the home, adjust the sound mix to individual preference and even splice a section from one conductor’s performance of a familiar piece into another’s. “Dial twiddling,” he wrote, “is an interpretive act.”

Recording could rescue whole musical genres from oblivion; Gould pointed out that recordings were a major factor in the postwar restoration of baroque music, especially on original instruments, to the marketplace.

“This repertoire — with its contrapuntal extravaganzas, its antiphonal balances, its espousal of instruments that chuff and wheeze and speak directly to a microphone — was made for stereo,” he wrote. Only after that pre-classical repertoire established its popularity in records did it find its way to the concert stage.

Gould was not exactly a pioneer in what his longtime producer, Andrew Kazdin, termed “creative lying.” The most famous early case involved a 1952 recording of Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde” in which the aging soprano Kirsten Flagstad was unable to hit a high C.

The producer, Walter Legge, called on his wife, soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, to record the note, which was dubbed in. The subterfuge was made public only years later.

Before Gould, such splices, inserts, dubbings and other tools of the recording engineers were generally seen as remedies for brief mistakes, sometimes of a single note. But he used them to fashion something new.

In 1966 he wrote of overcoming his dissatisfaction with two takes of a fugue from Book 1 of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, one take he considered “rather pompous” and the other overly jubilant — and both “monotonous.”

He solved the problem by using the first for the fugue’s opening and conclusion, and splicing in the second for the midsection, producing a version “far superior to anything we could at the time have done in the studio.”

Gould’s decision to abandon public recitals was brewing for years, possibly since the launch of his international performing career, which began in January 1955 with concerts in Washington and New York and would carry him across the U.S. and to Europe.

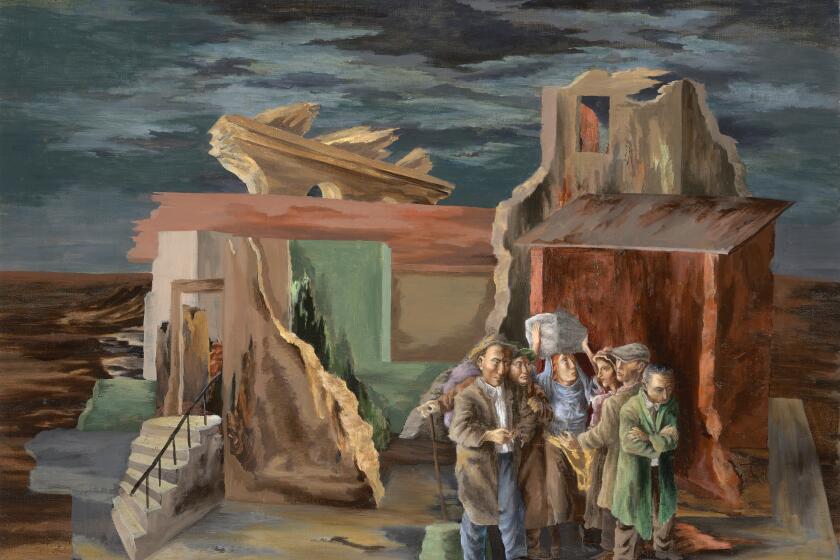

Column: Remembering when the government wasn’t afraid to let artists tell the truth about capitalism

A Depression-era federal program let artists depict the underside of American capitalism. Republicans killed it.

He had always detested traveling except by train, but hated even more what he saw as a “blood sport” pitting performer against audience. He saw concerts as “the frantic pursuit of a succession of daily events, momentary, ephemeral,” forcing performers to “calcify” their interpretations so they could be repeated over and over.

The recording studio, he felt, afforded artists the opportunity to perfect their vision of a piece in splendid isolation, and to rectify any flaws — and not only technical mistakes — in post-production.

Even while he was still giving concerts, Gould was known as an unreliable booking, prone to last-minute cancellations — he skipped a 1964 concert in Chicago three times before finally showing up. (It was his final public performance other than the Los Angeles recital.)

Indeed, when Leonard Bernstein came out on stage alone at the start of a performance with the New York Philharmonic on April 8, 1962, he felt constrained to notify the audience, “Don’t be frightened — Mr. Gould is here.”

The event became the most famous of Gould’s performing career. Bernstein’s purpose was to disavow Gould’s “unorthodox” interpretation of their program piece, Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1, though he said Gould was so important a musical thinker that he would perform it to Gould’s specified tempi anyway.

(Bernstein later revealed that when Gould visited him at his New York apartment before the performance, his appearance was so slovenly — another personal quirk — that his then-wife, Felicia Montealegre, pulled him into the bathroom to shampoo his matted hair and give it a trim. Moviegoers might recognize Montealegre as the character portrayed by Carey Mulligan in the 2023 Bernstein biopic “Maestro.”)

Pianist Gould foresaw tech role in music

Gould’s onstage behavior tended to provoke controversy. He slouched at the piano, left leg crossed over the right, seated on an ancient piano chair that his father had built, which placed him so low that he almost had to stretch his hands higher to reach the keyboard.

During a concerto performance, when not actually playing he waved his hands about as though conducting the piece, enraging music critics accustomed to a more solemn bearing from tuxedo-clad soloists. Ever willing in his earlier years to critique himself with a self-effacing grin, he referred in a 1959 documentary by the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. to “the justifiable complaints that I sometimes hear about my platform manner.”

As it happens, some of those tics transferred themselves to his recordings. On many albums one can hear the creaking of his chair, or a “hiccup” in some notes produced by the tight keyboard action he demanded from his pianos to produce the percussive, almost harpsichord-like sound that was his hallmark. Above all, there is his humming and singing audible in the background.

Columbia technicians spent years trying to suppress these artifacts in post-production, without notable success. In another 1959 CBC documentary, Columbia recording director Howard Scott is seen pleading with Gould before a take of Bach’s Italian Concerto for “a straight piano solo, without vocal obbligato.” A hearing of the recording proves that he didn’t get it.

But those were all part of the Gould mystique, accepted and appreciated by his listeners as though they brought them face-to-face with the artist himself. When they were heard on a Gould take, Kazdin reported, “Glenn always greeted them as one would long-lost friends.”

The influence Gould exerted on his fellow artists and the recording industry generally is incalculable. Columbia and its successors have never let the Gould library go out of print; with every advance in technology, the company remasters the recordings (most recently in 2015) and they always sell.

It’s as if by forswearing the evanescent experience of real-life performing, Glenn Gould gave himself eternal fame. And it happened in Los Angeles, where he ended one chapter of his career so he could embark on the next.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.