California bill would require state review of private equity deals in healthcare

- Share via

A bill pending in California’s Legislature to ratchet up oversight of private equity investments in healthcare is receiving enthusiastic backing from consumer advocates and labor unions but drawing heavy fire from hospitals concerned about losing a potential funding source.

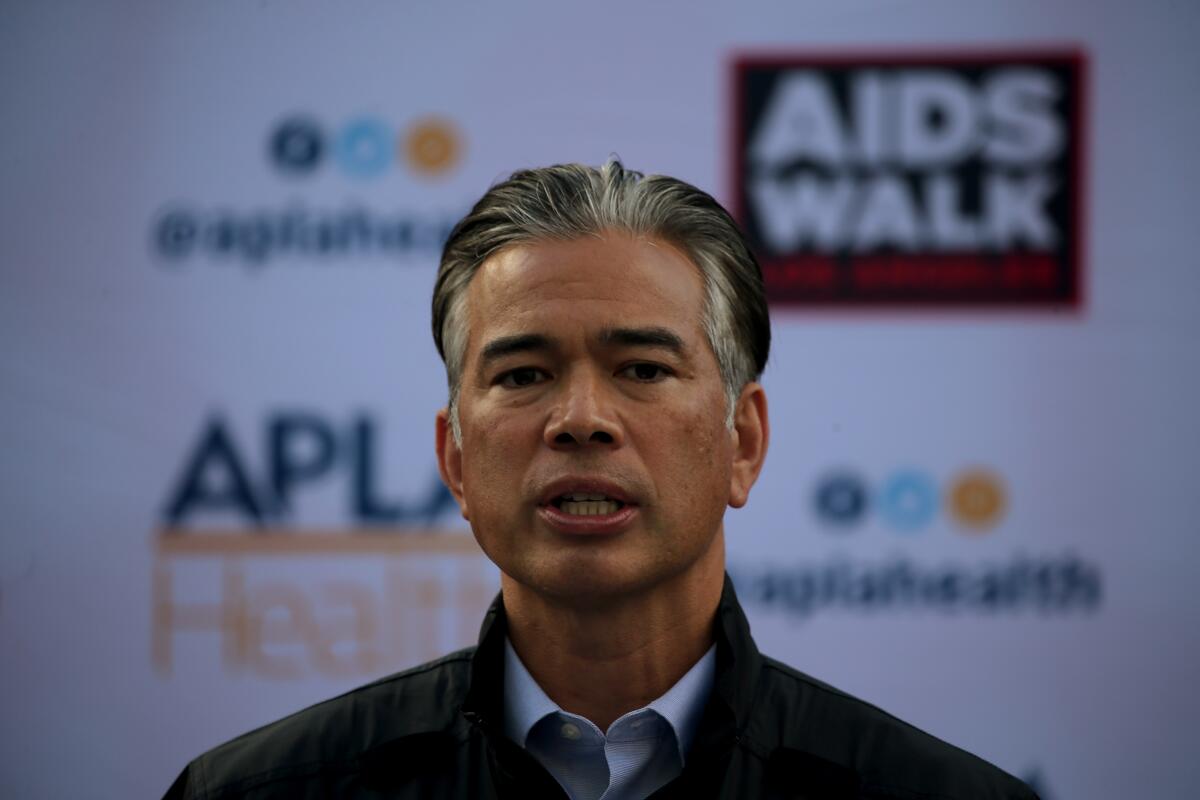

The legislation, sponsored by Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta, would require private equity groups and hedge funds to get approval from Bonta’s office for purchases of many types of healthcare businesses.

Private equity firms raise money from institutional investors such as pension funds and typically buy companies they believe can be run more profitably. They then look to boost the companies’ earnings and sell the assets for a profit.

This profit-first approach has been common in healthcare deals, and as private equity money has flooded into the sector it has set off alarms for critics and lawmakers amid mounting evidence that the deals often lead to higher prices, lower-quality care and reduced access to core health services.

Opponents of the bill, led by the state’s hospital association, the California Chamber of Commerce and a national private equity advocacy group, say it would discourage much-needed investment. The hospital industry has already persuaded lawmakers to exempt sales of for-profit hospitals from the proposed law.

“We preferred not to make that amendment,” Bonta said in an interview. “But we still have a strong bill that provides very important protections.”

Kamala Harris fought healthcare consolidation as California attorney general. She could escalate the fight nationally if she wins the presidency in November.

The legislation would still apply to a broad swath of medical businesses, including clinics, physician groups, nursing homes, testing labs and outpatient facilities, among others. Nonprofit hospital deals are already subject to the attorney general’s review.

A final vote on the bill could come this month if a state Senate committee moves it forward.

Nationally, private equity investors have spent $1 trillion on healthcare acquisitions in the last decade, according to a report by the Commonwealth Fund. Physician practices have been especially attractive to them, with transactions growing sixfold in a decade and often leading to significant price increases. Other types of outpatient services, as well as clinics, have also been targets.

In California, the value of private equity healthcare deals grew from less than $1 billion in 2005 to $20 billion in 2021 , according to the California Health Care Foundation. And while private equity firms are tracking the pending legislation closely, they so far haven’t slowed investment in California, according to a new report from the research firm PitchBook.

Multiple studies, as well as a series of reports by KFF Health News, have documented some of the difficulties created by private equity in healthcare.

Research published last December in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. showed a larger likelihood of adverse events such as patient infections and falls at private equity-backed hospitals compared with others. Analysts say that more research is needed on how patient care is being affected but that the effect on cost is clear.

“We can be almost certain that after a private equity acquisition, we’re going to be paying more for the same thing or for something that’s gotten worse,” said Kristof Stremikis, director of Market Analysis and Insight at the California Health Care Foundation.

Most private equity deals in healthcare are below the $119.5-million threshold that triggers a requirement to notify federal regulators, so they often slide under the government radar. The Federal Trade Commission is stepping up scrutiny, and last year it sued a private equity-backed anesthesia group for anticompetitive practices in Texas.

Lawmakers in several other states, including Connecticut, Minnesota and Massachusetts, have proposed legislation that would subject private equity deals to greater transparency.

Not all private equity firms are bad operators, said Assemblymember Jim Wood, a Democrat from Healdsburg, but review is essential: “If you are a good entity, you shouldn’t fear this.”

The bill would require the attorney general to examine proposed transactions to determine their likely effect on the quality and accessibility of care, as well as on regional competition and prices.

Hospitals must promptly report to the Los Angeles County public health department each time they try to collect medical debt from patients, under an ordinance backed Tuesday by county supervisors.

Critics of private equity deals note they are often financed with debt that is then owed by the acquired company. In many cases, private equity groups sell off real estate to generate immediate returns for investors and the new owners of the property then charge the acquired company rent.

That was a factor in the financial collapse of Steward Health Care, a multistate hospital system that was owned by the private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management from 2010 to 2020, according to a report by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, a nonprofit that supports the California bill. Steward filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in May.

Opponents of the legislation argue the prospect of having to submit to a lengthy review by the attorney general would damp much-needed investment in an industry with soaring operating costs.

“Our concern is that it will cut off funding that can improve healthcare,” said Ned Wigglesworth, a spokesperson for Californians to Protect Community Health Care, a coalition of groups fighting the legislation.

Private equity proponents point to what they say are examples of such funding helping to expand access to care in California.

Children’s Choice Dental Care, for example, said in a letter to state senators that it logs more than 227,000 dental visits annually, mostly with children on Medi-Cal, the health insurance program for low-income Californians. “We have been able to expand to 25 locations, because we have been able to access capital from a private equity firm,” the group wrote.

Ivy Fertility, with clinics in California and eight other states, said in a letter to state senators that private investment has expanded its ability to provide fertility treatments at a time when demand is increasing.

Researchers note that private equity investors are hardly alone when it comes to healthcare profiteering, which extends even to nonprofits. Sutter Health, a major nonprofit hospital chain, for example, agreed to a $575-million settlement of a lawsuit brought by then-Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra alleging unfair contracting and pricing.

“Anyone can do the things that private equity firms do,” said Christopher Cai, a physician and health policy researcher at Harvard Medical School. But, he said, private equity investors are “more likely to engage in financially risky or purely profit-driven behavior.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — an independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism. KFF Health News is the publisher of California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.