Take a break from the election and read this story about emoji karaoke

- Share via

Reporting from San Francisco — The soothing synths of Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” filled a foam-lined karaoke room — but no one was singing.

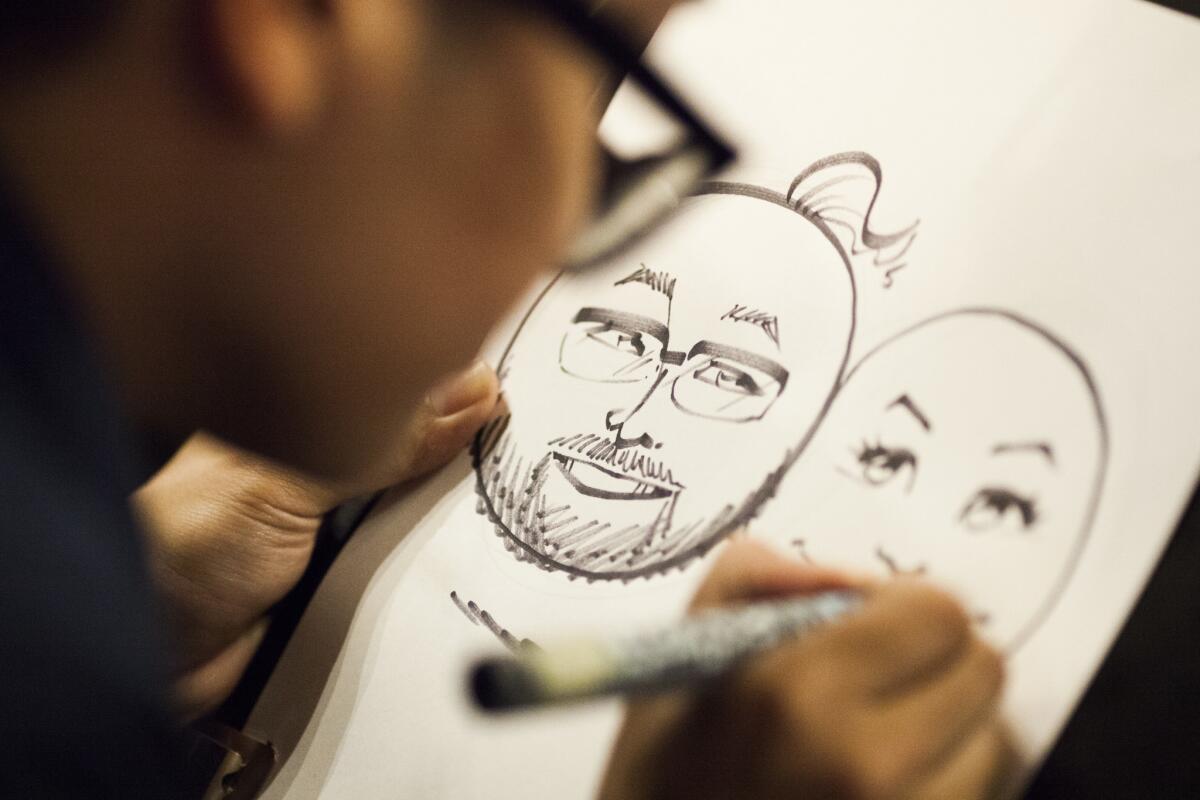

For participants, emoji karaoke is a silent affair.

The half-dozen contestants kept their noses in their phones, thumbs moving frantically as they looked for the perfect pictographs to illustrate Lauper’s lyrics: “If you’re lost” and “You will find me.”

To passersby, it may have looked like a gathering of distracted people. But this was Emojicon, a first-of-its-kind San Francisco conference dedicated to celebrating the yellow smiley faces and cartoonish food items, animals and hand gestures that make up today’s digital language.

Far from being a festival for the Bay Area’s tech wonks, the two-day event, which took place this weekend at the Downtown Westfield shopping mall, was an invitation for ordinary people to learn more about a digital phenomenon they helped create, and to play an active role in shaping its future.

A Swift Key study last year found that 74% of Americans use emojis every day. A study from the U.K. found that 80% of Brits regularly use emojis. When the research focused on users younger than 25, that number was 100%. Not too shabby for a tool the Unicode Consortium — the nonprofit group that standardizes languages on computers — added only six years ago.

“This is the only language everyone in the world can speak,” said Kate Miltner, a USC researcher who traveled to San Francisco to host the emoji karaoke tournament. “But here’s the thing: Because they’re cute and funny, people don’t take them very seriously.”

Which is why Emojicon exists, according to organizers Jeanne Brooks and Jennifer Lee, who see the event as an opportunity to get people to pause and think about something they likely use every day, and lift the veil on how emojis are pitched, approved and designed.

“We wanted to support and open up the process of emoji,” said Brooks, who noted that even though the Unicode Consortium is one of tech’s most transparent nonprofit tech organizations — making public even its internal emails — its website is so dense and its profile so low that co-founder Mark Davis has taken to calling its committees “shadowy.”

Few people know, for example, that anyone can pitch an emoji. Fewer still know that once an emoji is accepted, it’s part of Unicode forever — no emoji has ever been revoked — which is why the consortium approves only 70 or so each year.

And most people who use emojis don’t realize that Unicode itself isn’t responsible for the appearance of emojis — it’s up to vendors such as Apple, Google, and Facebook to come up with their own designs. This accounts for why the peach emoji on iOS resembles a voluptuous rear-end, while the same emoji on Facebook looks more like a stone fruit. (Apple recently signaled intentions to change its peach to be more fruit-like in appearance, much to the dismay of those who prefer their emoji to stay cartoonish or sexual. One woman attended Emojicon dressed as the Rubenesque peach emoji with “R.I.P.” written across the back.)

“Emoji is permeating culture,” Brooks said, “so we wanted to bridge the gap between the people using emoji and the Unicode Consortium.”

The organizers pulled in sponsorship from companies that sit on the consortium, such as Google and Adobe, and firms that have lobbied for emojis relevant to their business, such as Taco Bell (taco emoji) and Panda Express (dumpling emoji). Tickets started at $10 for game events and film festival and went up to $500 for an all-access pass, including an invitation to its VIP dinner with members of the emoji subcommittee and a curator from the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which recently added to its collection the original set of emojis.

The event sold more than 500 tickets and attracted developers, artists, academics, and even passersby who dropped in while shopping at the mall to see what the fuss was all about.

“I have no idea what this is,” said Derrick Chang, 22, who attended Emoticon’s launch party the night before. “But I use emoji all the time — it’s how we communicate now.”

Mack Flavelle, 35, didn’t know what to expect from Emojicon. The Canadian software developer traveled from Vancouver to attend after first hearing about it on Twitter.

“It kind of blew my mind to learn that anyone can submit an emoji,” he said. “With emoji, I can make something that literally millions of people will use. Now I’m obsessed with it. This is going to be my legacy. I will design an emoji that my kids will use.”

Back in the karaoke room, a competitor with salt and pepper hair tapped away on his phone, interpreting the song through emojis. To represent the lyrics, “If you’re lost you can look and you will find me,” he chose a hand gesture emoji, a question mark, a pair of eyes, the emoji of a legal document (“will”), another pair of eyes and another hand gesture.

“What is this?” said the youngest competitor, an elementary school girl covered in face paint, who grimaced at the song only older people seemed to recognize.

“Cyndi Lauper!” her mom yelled from the audience.

The girl shrugged, and started tapping away on her phone, pulling up the clock emoji, then a rightward-pointing arrow emoji, and another clock emoji to represent “Time After Time.”

Twitter: @traceylien

ALSO

California’s 17 propositions, explained with emojis

Meet the shadowy overlords who approve emojis

David Bowie is memorialized in emoji form in latest Apple iOS update