Mother watched as daughter gunned down in Gilroy: ‘She took my hand and looked up at the sky’

- Share via

SAN JOSE — The 12-year-old girl sat on the bottom bunk bed where her older sister, Keyla Salazar, used to sleep.

Lyann Salazar held a pencil in one hand and, in the other, an iPhone displaying a picture of Keyla. She drew a portrait of Keyla on a blank page of her notebook.

Lyann and Keyla used to share the small bedroom in their San Jose home, but now Lyann sleeps there alone, with just Keyla’s Chihuahua, Lucky, to comfort her.

“She’s drawing and writing to her sister to give her a last goodbye,” the sisters’ grandmother, Betzabe Vargas Fabes, said in Spanish.

Keyla was one of three people shot to death last week at the Gilroy Garlic Festival, and in a few days her family would gather for her funeral.

Lyann looked up from the bed, but remained silent as she sketched outlines of her sister’s face.

The room was simple, just how Keyla liked it.

Scattered about were reminders of Keyla: A pink teddy bear with the word “princess” sewn across the front. Plastic stars the girls had stuck on the ceiling that lighted up at night. Several pairs of Keyla’s headphones that she used while making YouTube videos and animations on her computer and iPad.

“The sisters were so united. Keyla would draw there, and she [Lyann] would draw here,” Fabes, 58, said, pointing to opposite sides of the lower bunk.

On Saturday, six days after the shooting in Gilroy, a gunman opened fire near a shopping mall in El Paso, Texas, killing 22 people and wounding more than two dozen others. It was the same day that Keyla’s family and community honored her at a vigil at Latino College Preparatory Academy, the school that she was set to attend this fall.

The 21-year-old gunman arrested in the El Paso massacre is believed to have written a hate-filled manifesto disparaging Latino immigrants.

Gilroy shooting: FBI is opening domestic terrorism investigation into festival attack

A law enforcement official says the FBI is opening a domestic terrorism investigation into the shooting that killed three people and injured 13 others at a popular California food festival.

Law enforcement officials said they have not uncovered any evidence that the Gilroy gunman targeted a particular race. But before the shooting, he posted a photo on Instagram with a caption that read, in part: “Why overcrowd towns and pave more open space to make room for hordes of mestizos ...?”

As in Gilroy, many of the El Paso victims were Latinos. “At this point we are really traumatized. We feel like we can’t go to the grocery store because we feel like something is going to happen,” said Keyla’s aunt, Katiuska Pimentel, 24. “We feel their pain.”

In their grief, Keyla’s family remembered the girl who loved animals and drawing and telling stories through animation. She had autism, which caused her to struggle in school and made it difficult to communicate with her peers. Still, she persevered and graduated in June from middle school. Perched on a shelf in the living room is a certificate from Keyla’s school naming her Most Artistic.

“She was so happy to graduate because she had to work really hard to get her grades,” Pimentel said.

Her favorite animation character was “Stitch,” the frantic blue creature from the Disney movie “Lilo & Stitch.” At least three Stitch stuffed animals lay around her home, sitting on the living room couches and in Keyla’s bedroom.

Her grandmother clutched to her chest a Stitch sweatshirt her family bought her on a recent trip to Disneyland. The last picture the family has of Keyla is from that trip. She’s wearing a red shirt, smiling. The photo, along with others of Keyla, was displayed among an abundance of white roses and lilies at an altar set up in the living room.

A steady stream of visitors has stopped by the family home in recent days, offering condolences, food, flowers, hugs and tears. The days were busy and mournful — a welcome distraction, but also a constant reminder of their loss.

Every time an uncle called and another teacher came to sit on the family couch, Keyla’s mother, Lorena Pimentel de Salazar, 35, found herself reliving the minutes of the shooting.

When her cousin knocked at the metal white door on Friday afternoon, he embraced her.

“I can’t sleep, I can’t sleep,” she told her cousin, Hans Bludau, in Spanish. She pointed to her head.

“I have the dreams right here every night ... I saw when he was shooting.”

When they first heard the shots, Pimentel de Salazar started running with her other two daughters, Lyann and 4-year-old Dasha, while her partner stayed behind with Keyla, who was unable to run because of medical problems.

She saw her daughter fall to the ground.

“She looked at me, and she could no longer speak,” Pimentel de Salazar said. “She took my hand and looked up at the sky.”

Then Keyla closed her eyes.

“In that moment I knew that she was up above us.”

Keyla came from an immigrant family — her mother is from Peru, her father from Mexico.

Pimentel de Salazar said she came to the United States almost 20 years ago, and her daughters all were born here. Keyla’s grandmother, Vargas Fabes, joined the family in the U.S. about two years ago.

“We love the United States,” Vargas Fabes said. A former schoolteacher, Vargas Fabes said Peru’s education system could not offer the opportunities her granddaughters had here.

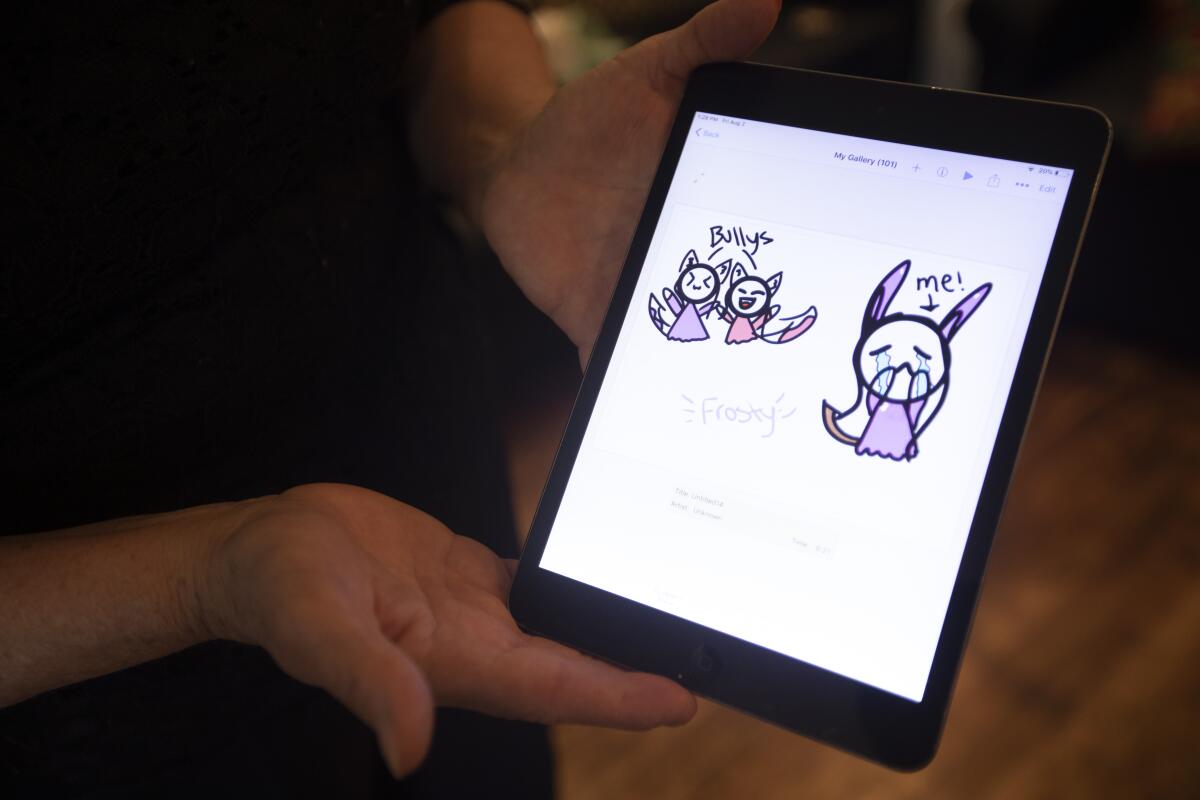

On Friday, Vargas Fabes was eager to show visitors the drawing the family had recently found on Keyla’s iPad. But some images took the family by surprise.

“This one made us cry,” she said, pulling up one sketch. It showed two characters dressed in different shades of pink, with what looked like cat ears and fox tails, laughing. Above them, Keyla had written the word “Bullys.”

On the other side of the screen, she wrote “Me!”, with an arrow pointing to another animal-like character, whom she labeled “Frosty.” Blue tears streamed down Frosty’s face.

“She suffered from bullying at school because of her disability,” Keyla’s mother said.

Sometimes, kids would pull a chair out from under her when she tried to sit down, or make fun of her height, since she was taller than most her age.

It never seemed to bring her down too much, the family said, but the bullying image on the iPad — which they were seeing for the first time — suggested a profound inner hurt.

“She was happy regardless of everything she had to go through,” said Keyla’s aunt.

That afternoon, Pimentel de Salazar had gone to pick up Dasha from daycare. Dasha, too, had seen her sister get shot, and the caretaker suggested she needed therapy. Dasha had been telling the other children that a “bad man”could come get them.

But after she was brought home, Dasha ran into the house happily sucking a lollipop and holding a stuffed rainbow-colored unicorn, while her mother followed, the bags under her eyes deeper than they were the day before.

At a fundraiser that Friday evening, dozens packed into what looked like an old garage converted into a dance studio near Roosevelt Park in San Jose.

Pimentel de Salazar’s Zumba teacher, Roberto Roman, 32, had organized a fundraiser for Keyla’s family, along with several other Zumba teachers in the neighborhood.

Those in attendance joined hands and recited the Padre Nuestro, or “Our Father.” Then they danced.

“We are with Lorena!” Roman, 32, bellowed in Spanish from the stage, referring to Keyla’s mother, as he pumped a fist into the air. The audience clapped and cheered.

A short time later, the music was lowered and people began to whisper, “llegó la mama.” “The mother has arrived.”

Dressed in black, Pimentel de Salazar walked in accompanied by six family members. The crowd parted and the music stopped.

Vargas Fabes held her grieving daughter’s arms to help her stand as both of them made their way to the stage. The mother’s voice was shaky, her eyes teary as she lifted the microphone.

“I want to thank you with all my heart,” she told the crowd. “I don’t have adequate words for everything that you are all doing.”

Her few words were met with a burst of applause and a chant: “Te queremos, Lore, te queremos.” “We love you, Lore, we love you.”

The next day, Pimentel de Salazar and her family attended a vigil for Keyla. Dasha comforted her mother and grandmother as singers performed to honor Keyla.

Pictures and images from the family home were brought out onto tables overlooking the high school lawn. Keyla’s stepfather remained a quiet observer, occasionally embracing Dasha behind the crowd, his arm still bandaged from the bullet that grazed him six days earlier.

As the sun set, volunteers handed out candles as they surrounded Keyla’s mother.

Then came a moment of silence for Keyla, for the other Gilroy victims, and for the people killed the same day in El Paso.

On Sunday, Keyla’s living room altar radiated with color. White roses and lilies were replaced with bright pink, orange and red daisies.

That day marked one week since the shooting. It also was Keyla’s 14th birthday.

As the family gathered in San Jose’s Emma Prusch Farm Park, they placed framed copies of her iPad drawings of Frosty and the bullies on the tables.

There were pinatas and cake, chorizo and asada tacos. Dozens of people attended, and the little kids played.

“She’ll be 14, but she’s not here with us,” Pimentel told the crowd.

On the day of her death, Keyla had written a note to her family asking for a golden retriever puppy for Lyann. Keyla already had her Chihuahua, Lucky, and she thought her sister deserved a pet too.

At the birthday party, San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo presented Keyla’s family a certificate to pick up a golden retriever puppy, with care paid for.

As a mariachi band played “Las Mañanitas,” a Mexican birthday song, Keyla’s mother occasionally looked up at them, sometimes pulling up her phone to take videos, sometimes crying.

Despierta, mi bien, despierta, the mariachis sang.

Wake up, my dear, wake up.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.