Heavily redacted texts show Mayor Garcetti’s request for home to be checked during Woolsey fire

- Share via

On a November afternoon, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti texted the city’s fire chief to ask how much destruction the Woolsey fire had caused in a wealthy gated Ventura County neighborhood.

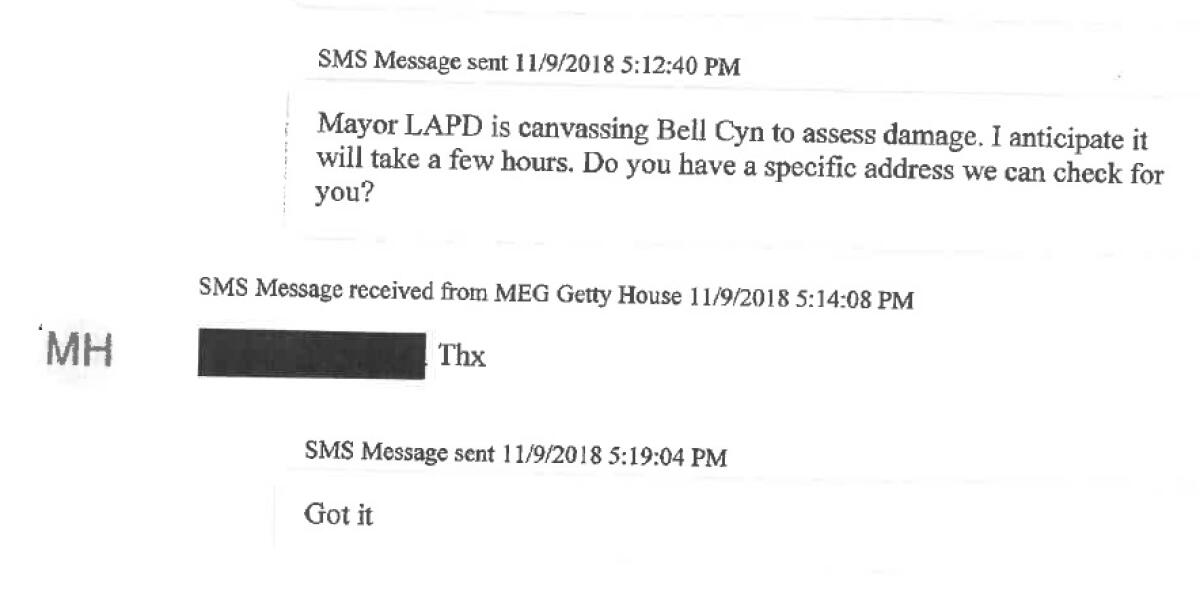

Over the course of the next few hours, the mayor and the Fire Department chief, Ralph Terrazas, went back and forth over the fate of Bell Canyon. Eventually, the chief asked Garcetti whether he wanted any specific home checked, and the mayor provided an address, according to public records obtained by the Los Angeles Times of text messages between L.A. leaders.

The 56 pages of text messages provide a glimpse into an issue fire officials noted in a report last year: that politicians asking firefighters to check on specific addresses complicated their ability to fight the fast-growing Woolsey fire. But in a move that government accountability experts called legally questionable, L.A. officials provided The Times with heavily redacted records of the communications, obscuring key details such as specific addresses.

Both the L.A. city fire and Garcetti’s office blacked out the address of the home the mayor asked to be checked. They argued that providing it to The Times constitutes an “unwarranted invasion of personal privacy” and that the information is exempt from disclosure under the state records act.

The mayor’s spokesman, Alex Comisar, said Garcetti asked on Nov. 9 about Bell Canyon, which the Los Angeles Fire Department is responsible for defending under a contract with the Ventura County Fire Department, because he was “concerned for the safety of all those affected by the wildfire and the city’s brave and skillful first responders on the scene.”

“In the text messages,” Comisar added, “Mayor Garcetti asked for information about Bell Canyon and West Hills because both communities were threatened by the wildfire, evacuated and protected by Los Angeles city firefighters, and he knows residents in both communities.”

But public records watchdog groups criticized withholding the address from the public.

Glen Smith, legal fellow at the First Amendment Coalition, said government agencies can redact addresses in limited scenarios, such as if someone needed medical assistance or was a domestic violence victim who asked that their name be withheld.

“But the exemption is not supposed to enable the mayor to ask about someone’s house and then refuse to identify who that individual was,” Smith said. “The exemptions are not supposed to give political cover to an elected official.”

Consumer Watchdog President Jamie Court said given Garcetti’s request, the address is “absolutely a public record,” as taxpayer money was financing the efforts of firefighters and police officers during the Woolsey fire.

“That’s the price of public office -- and the use of public resources in the middle of a public emergency,” Court said. “He didn’t ask his babysitter to check. He asked the Fire Department, and if he wasn’t mayor, no one would have checked.”

In early May, The Times requested the text messages, emails and other communications between Garcetti’s executive team and Fire Department leaders about the Woolsey fire after publishing a story in late April that revealed that the Fire Department said their response to the Woolsey fire was complicated by requests from politicians.

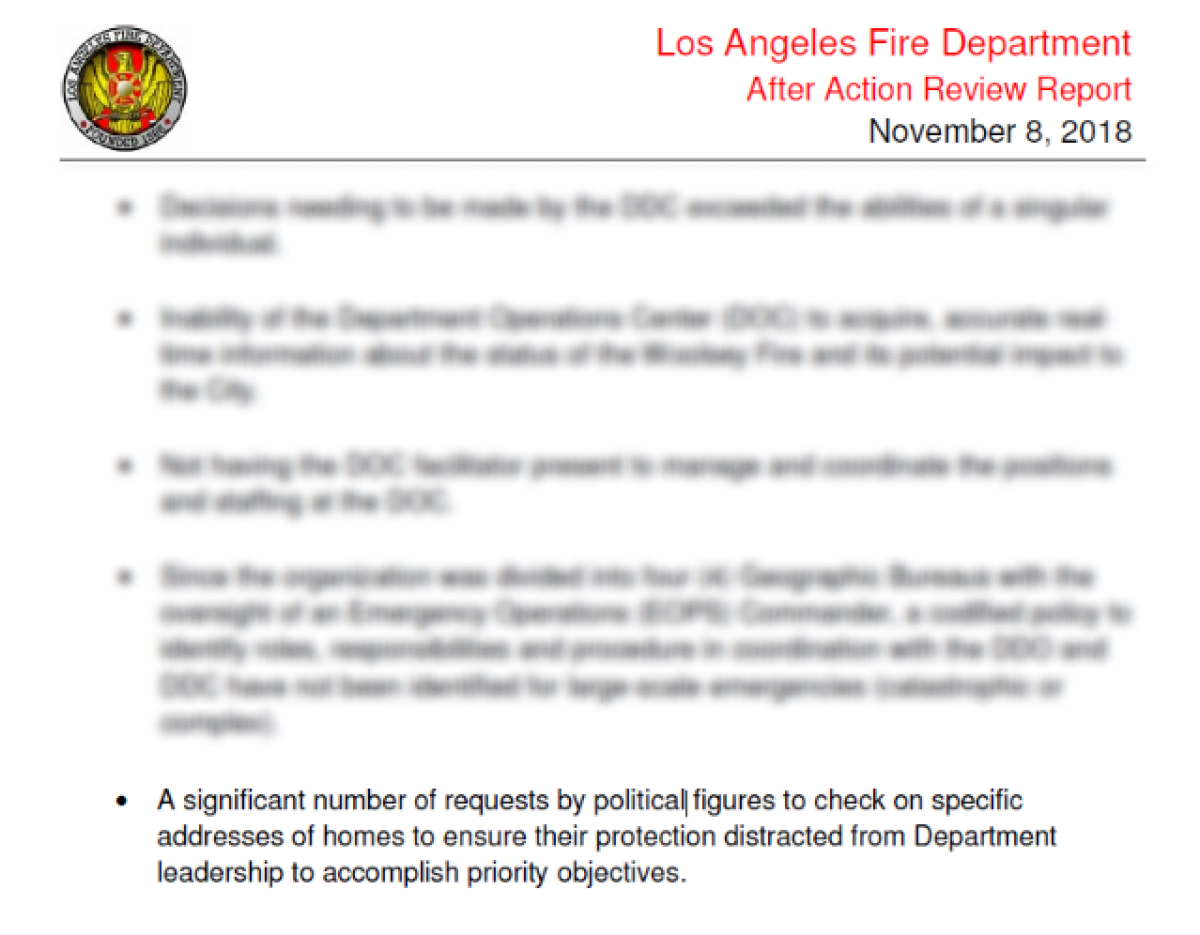

“A significant number of requests by political figures to check on specific addresses of homes to ensure their protection distracted from Department leadership to accomplish priority objectives,” the LAFD Woolsey fire after-action report reads.

However, in recent interviews and emails with The Times, L.A. city fire officials did an about-face regarding that statement -- and gave contradictory information about its inclusion in the after-action report.

Terrazas, who was appointed chief by Garcetti in 2014, said in an interview July 17 that the inclusion of the statement in the after-action report was a “miscommunication” and that the statement itself was inaccurate.

No one, including the mayor, received special treatment from the Fire Department during the Woolsey fire, he said. Rather, a “scribe” taking notes for the after-action report incorrectly sent the statement to the author of the report after Terrazas told him it was wrong.

The Woolsey fire started on Nov. 8 but made its destructive march to the Pacific Ocean the morning of Nov. 9.

“Approximate number of lost homes in Bell Canyon is 10,” Terrazas texted the mayor after he asked about damage in Bell Canyon.

“Do we know what streets?” Garcetti asked.

“Homes are being reported lost on Stirrup Lane in Bell Canyon,” Deputy Mayor Jeff Gorell, who oversees public safety for Garcetti, said in the group text, which was part of public records obtained by The Times. “But haven’t seen anything official.”

The fire chief said he would ask an incident commander to gather the information, before asking the mayor: “Do you have a specific address we can check for you?”

Two hours after Garcetti responded with an address, the home was checked and determined to be safe.

The conversation was part of text messages provided through a California Public Records Act request that The Times made as part of its investigation into the concerns raised in the Fire Department’s after-action report.

The Woolsey fire was the most destructive fire in Los Angeles and Ventura counties’ modern histories, burning almost 97,000 acres, destroying hundreds of homes and killing at least four people. No homes were destroyed in the city of Los Angeles.

Terrazas said that during fire training in early April – before The Times published its story – the matter of political requests came up during a presentation based on the after-action report. Terrazas said he told the room of chief officers that the statement was inaccurate and shouldn’t have been included because requests from political figures were not a significant issue during the Woolsey fire.

But about a week after the April training, when The Times contacted the LAFD regarding the “political figures” statement’s inclusion in the presentation and after-action report, no one from the department raised any issues about its accuracy.

Instead, Assistant Chief Tim Ernst told The Times in an interview that same month that he used the after-action report to create the training presentation and brought up the matter of special requests with chief officers because he wanted them to know about the inevitability of these types of requests in L.A.

He said in the interview that he did not know which politicians made special requests during the Woolsey fire.

“One of the things I really wanted to mention, especially to the newer chiefs in the room, is that living in the city of L.A. or the county of L.A., we have to understand we probably have some of the wealthiest communities in America, and with that comes a certain amount of political power,” Ernst said in that interview.

Peter Sanders, an LAFD spokesman, said in an email July 19 that Terrazas investigated in mid-July why the statement was included in the after-action report after The Times asked further questions about it and realized it didn’t get corrected before the report was finalized.

As of mid-July, the department had not corrected the after-action report, which was completed late last year.

It was only after The Times requested and received a copy of the text messages shared between Terrazas, Garcetti and other executive staff members that the LAFD raised the issue of the report’s accuracy.

When asked about the text messages sent to Terrazas, the mayor’s office said in a statement that no LAFD operations were affected by Garcetti’s request because it was the Los Angeles Police Department that was performing the canvass of Bell Canyon.

“When asked by the Fire Chief, Mayor Garcetti requested information from the LAPD’s canvas of structures in the evacuated neighborhood,” the statement read. “No Fire Department operations were affected by the Mayor’s request for information from the Police Department’s canvas of the neighborhood.”

Terrazas said during a large-scale emergency, the department is flooded with requests from the general public to check on homes and that generally, there might be a list compiled, and firefighters in the area check on homes if they’re able to.

“You get on the radio, and you have an address in question, and [a firefighter] may be on that street, and you ask that person, ‘Hey, what’s the condition of that block?’ and it’s simple as that,” Terrazas said. “Sometimes it can be handled in a matter of a few seconds, and sometimes if we’re busy, it can take hours, or maybe days.”

This was the case when Rebecca Ninburg, a member of the Los Angeles Board of Fire Commissioners, asked the department to check a home.

In a group text with Terrazas, Deputy Mayor Gorell and LAFD Chief of Staff Graham Everett, Everett accidentally sent images of a home in Bell Canyon to the group and then apologized, noting the images were for Ninburg. The conversation occurred around 6 p.m. Nov. 10, after the Woolsey fire had died down substantially from the previous day.

Ninburg said in an interview with The Times that she asked someone with the department to check on the home of close friends who live in Bell Canyon, whose identity she said she was not comfortable disclosing. The address was not included in Everett’s text.

Ninburg said she couldn’t remember exactly who she asked at the LAFD, but that she stressed to the person that the request should not be made a priority. It was a few days before she heard back, she said.

“It’s an emergency time, and I would never in a million years ask people to stop doing what they’re doing for something like this,” Ninburg said. “I think our department waited, they assessed the situation, and came back days later after fires had died down.”

The Woolsey fire destroyed an estimated 27 homes in Bell Canyon and damaged another 17, according to a Ventura County damage assessment.

The home that Garcetti wanted checked was apparently unscathed.

“Everything is fine at [redacted],” Terrazas responded at 7:20 p.m. Nov. 9, just over two hours after the mayor asked.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.